China's Premier Li Keqiang walks towards the stage to make a speech during the opening session of the National People's Congress at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on March 5, 2016. In his speech, he unveiled a five-year development plan that included boosting funding for research and making less bureaucracy for scientists.

If the US continues to slash funding for science and research, while tightening immigration rules and making it harder for potential researchers to study and work in the country, the primary beneficiary will be China.

At least, that’s the warning from a Nobel Prize-winning chemist.

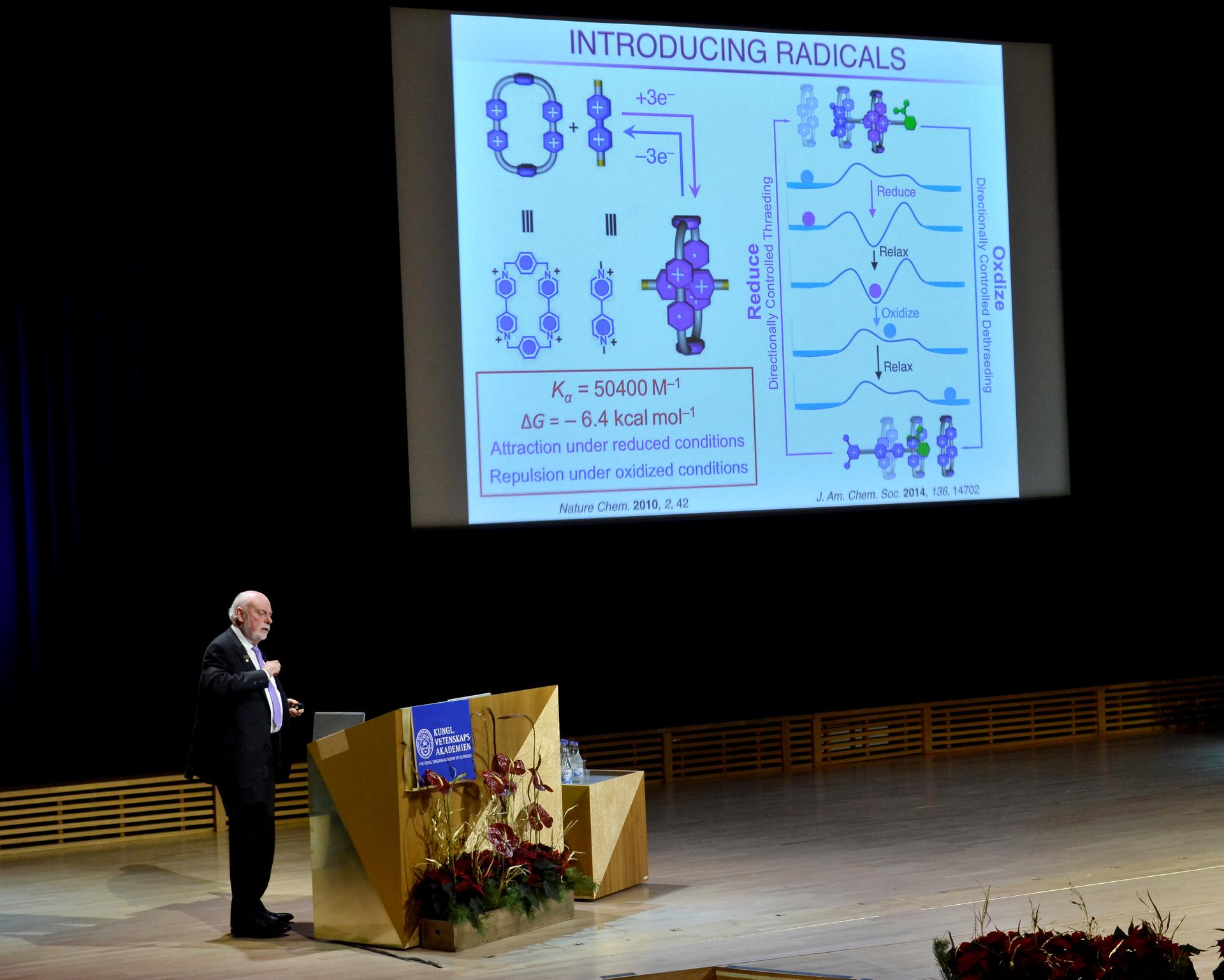

On Jan. 20, the day of President Donald Trump’s inauguration, Sir J. Fraser Stoddart was in Beijing to speak at an academic conference sponsored by the Chinese government. The Chinese premier, the country's top economic official, Li Keqiang, was in attendance. The two dined afterward, but Stoddart recalls that Li didn't seem to pay much attention to his food. Instead, he quizzed the chemist, who won the prize for his work designing molecular machines at Northwestern University outside Chicago. Li wanted to know how Stoddart became a scientist and found support for his research. He wanted to understand how the Chinese academic and research system could be improved and pressed Stoddart for his honest opinions.

The conversation veered to the Scottish Enlightenment, a period in the 18th and early 19th century when Scotland became the center of artistic and intellectual output in Europe. At the heart of it were intellectual clubs for discussion and debate, where poets like Robert Burns and economist Adam Smith rubbed shoulders and exchanged ideas. Stoddart, who was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, sees the era as an example of how bringing together thinkers from different backgrounds can lead to a dramatic leap in the production of knowledge. He describes the Scottish Enlightenment as a "mix of people that created sheer magic in a very small country."

Li followed the discussion intensively and jumped in, as well.

"He was anxious to know how this had happened, and he was very well-informed. He knew all about the Scottish Enlightenment, and he lit up when I talked about the effect this era had had on me," Stoddart says.

Follow: We're keeping up with Sir J. Fraser Stoddart as he works through the Trump years.

The relation between science and economic growth is a pet topic for Li. In March 2016, he gave a speech to the National People’s Congress in which he unveiled a five-year development plan that included boosting funding for research and making less bureaucracy for scientists. And it hasn’t been all talk. According to the latest data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, China spends the second most on research and development of any country, at $377 billion and growing. That is just over 2 percent of its gross domestic product. The US still tops the list, spending $463 billion or 2.8 percent of its GDP.

China is slowly catching up in its investments in science. Under the Trump administration, the US seems headed in the opposite direction. Trump’s proposed budget for 2018 includes slashing the National Science Foundation, which distributes grants to research projects, by $776 million. It also hits medical research hard, with a long list of agencies facing dramatic funding cuts, including the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, which could see a reduction of $1.3 billion, or 17 percent of its operating budget.

The Trump administration does not see these cuts as a signal that the US is giving up its position in science. Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney told reporters in May that cuts to the National Science Foundation and other entities target programs related to climate change.

“Does it mean that we are anti-science?” Mulvaney said. “Absolutely not. We're simply trying to get things back in order to where we can look at the folks who pay the taxes, and say, 'Look, yeah, we want to do some climate science, but we're not going to do some of the crazy stuff the previous administration did.'”

As of last week, the science division of the White House's Office of Science and Technology Policy — which was established by Congress in 1976 and had nine people working on science policy issues during the Obama administration — is now unstaffed in the Trump administration.

Richard Suttmeier, an expert on China’s research policy at the University of Oregon, believes these contrasting approaches to leadership in science are telling.

“China is already gaining ground on the US as a center for research. The Trump budget proposal is seemingly insensitive to the important role that federal government support plays in maintaining US scientific leadership and excellence,” he writes in an email. “The apparent disregard for science-based facts in the making of policy, which seems to be characteristic of this administration, contributes to the overall degrading of national culture which may be as serious, or more serious, than budget stringency.”

Meanwhile, when the Trump administration enacted the first version of their ban on travel from six mostly Muslim countries, hundreds of scientists, some with green cards, were blocked from entering the country. The ban has since been challenged in court and will now exempt those who have “bona fide relationships” in the US or have been offered jobs or opportunities to study or lecture at US universities. In April, Trump signed an executive order that called for a review of the H-1B visa program, through which skilled workers, including many in scientific fields, obtain permission to work in the US.

Stoddart believes that the climate around immigration in the US could drive talented scientists away, as many will be tempted to go where they can more easily obtain visas to work and funding for research.

"They have other choices, and the best and brightest and best will start to say, ‘Well, maybe we should go to China, maybe we'll go to Germany, maybe we'll go the Netherlands.’"

He sees attracting the “best and the brightest” as a practical matter. Stoddart has calculated that during his 50 years of working in chemistry research, he’s worked with 417 people from 47 different countries. For him, getting the right people together, like in the Scottish Enlightenment, is more important than funding. It creates what he calls a “unique lab culture,” centered around a common goal.

“The magic comes when you have open borders, open doors, and you can bring in people from all over the world,” he says. “I mean, you can hire the best and the brightest, and that's absolute magic when you bring them together.”

And as China increases its investment in science, young Chinese scientists, in particular, might be less interested in coming to the US.

"We'll see quite a change. We'll lose a lot of talent from China. I could see that happening very quickly. As the Japanese did many years ago, they'll just decide, 'Well, we can train our own people,’" Stoddart says. And other scientists agree.

But the US still has clear advantages in research and attracting talent. China, Stoddart says, still has a long way to go to create a less hierarchical academic system. Suttmeier points out other obstacles.

“Some centers of excellence are beginning to emerge in China and are attracting foreign researchers, although some aspects of the Chinese research environment — language difficulties, pollution, bureaucratic procedures, political controls, etc. — may limit the appeal for foreign researchers of making career commitments to China,” he says.

Still, both Stoddart and Suttmeier agree, the trends are in China’s favor.

"I think the long-term significance will be that China will steal the march on the United States and the rest of the world,” Stoddart says. “On the other hand, I am still optimistic that the United States still has a culture that will allow it to come roaring back under leadership that is different from the current leadership.”