About 30 Muslim families worship at the Islamic Society of Joplin, Missouri.

Six years ago, the city of Joplin, Missouri, was hit by a tornado almost a mile wide. It killed 158 people, flipping over cars and leaving piles of splintered beams where houses once stood.

But along with the destruction came something else: a sense of solidarity among Joplin’s followers of different religions. “It happened to all of us. It didn’t happen just to the Christians,” said the Rev. Frank Sierra, an Episcopal priest who helped organize an interfaith service soon after the tornado.

When disaster struck the city of about 50,000 for a second time, five years ago, the interfaith community was ready to respond.

The trouble started in summer 2012. About 30 Muslim families live in Joplin, and many of them were fasting during the month-long Islamic holiday of Ramadan. One evening, Imam Lahmuddin, who ran the Islamic Society of Joplin out of a converted church, invited the local Episcopal congregation to visit.

“They stayed late that night,” Lahmuddin recalled. The Christians and Muslims were glad to meet one another. They broke the fast together. “We had conversation, we had food, and good companionship.”

Sierra was one of the visitors. “I was hoping to make a connection,” he said. He was impressed by the daily discipline of the Ramadan fast. “I thought, ‘these people are really into their faith.’”

The sense of unity in Joplin made it all the more shocking when, early the next morning, Lahmuddin’s phone rang. Something was happening at his mosque. He got in the car and started driving. “When I approached the building, I saw from far away smog in the sky,” Lahmuddin said.

The mosque was on fire. All that was left were some beams and a pile of smoldering wood where the mosque once stood.

Lahmuddin knew right away that the fire wasn’t accidental. Two months earlier, a man had been caught on camera trying to burn down the building.

The imam felt sadness, but he also thought, immediately, that he should trust God to keep him safe. “So I just tried to calm down,” he said. “Cannot do anything.”

As firefighters swarmed the site that morning, local Muslims started to arrive for the morning prayer. While they tried to deal with the shock, they knelt down on the grass and prayed.

Then, members of the Joplin Interfaith Coalition started coming by. “I drove there and saw the destruction that had been created,” said Paul Teverow, a local professor who belongs to the United Hebrew Congregation in Joplin. “I was just horrified to think that something like this could happen here,” he added. “I wanted to make it clear, and I wasn't alone here, that these people are part of our community. That an offense against them is an offense against all of us.”

That week, the Joplin Interfaith Coalition organized another breaking of the Ramadan fast — this time, at St. Philip’s Episcopal Church. A member of the coalition drove hours to Springfield, Missouri, to pick up specially prepared chickens. Lahmuddin led evening prayers inside the church.

Father Sierra said that, unfortunately, he wasn’t shocked by the fire. He sometimes hears comments in his own parish that seem Islamophobic. “I’ve heard it from side remarks: ‘Oh, they’re all terrorists,’” he said. “It’s sad. Where am I missing out in teaching? What part of the Bible am I not emphasizing? Because that’s not what Jesus teaches.”

The culprit behind the mosque burning, Jedediah Stout, was caught a year later. He pleaded guilty not only to the mosque fire, but also to an attempted arson at Planned Parenthood in Joplin. He told federal investigators that he didn’t like Islam and he didn’t believe in abortion.

In the months following the fire, donations poured in from across the country. The Muslim community raised enough money to build a new mosque. It opened in 2014.

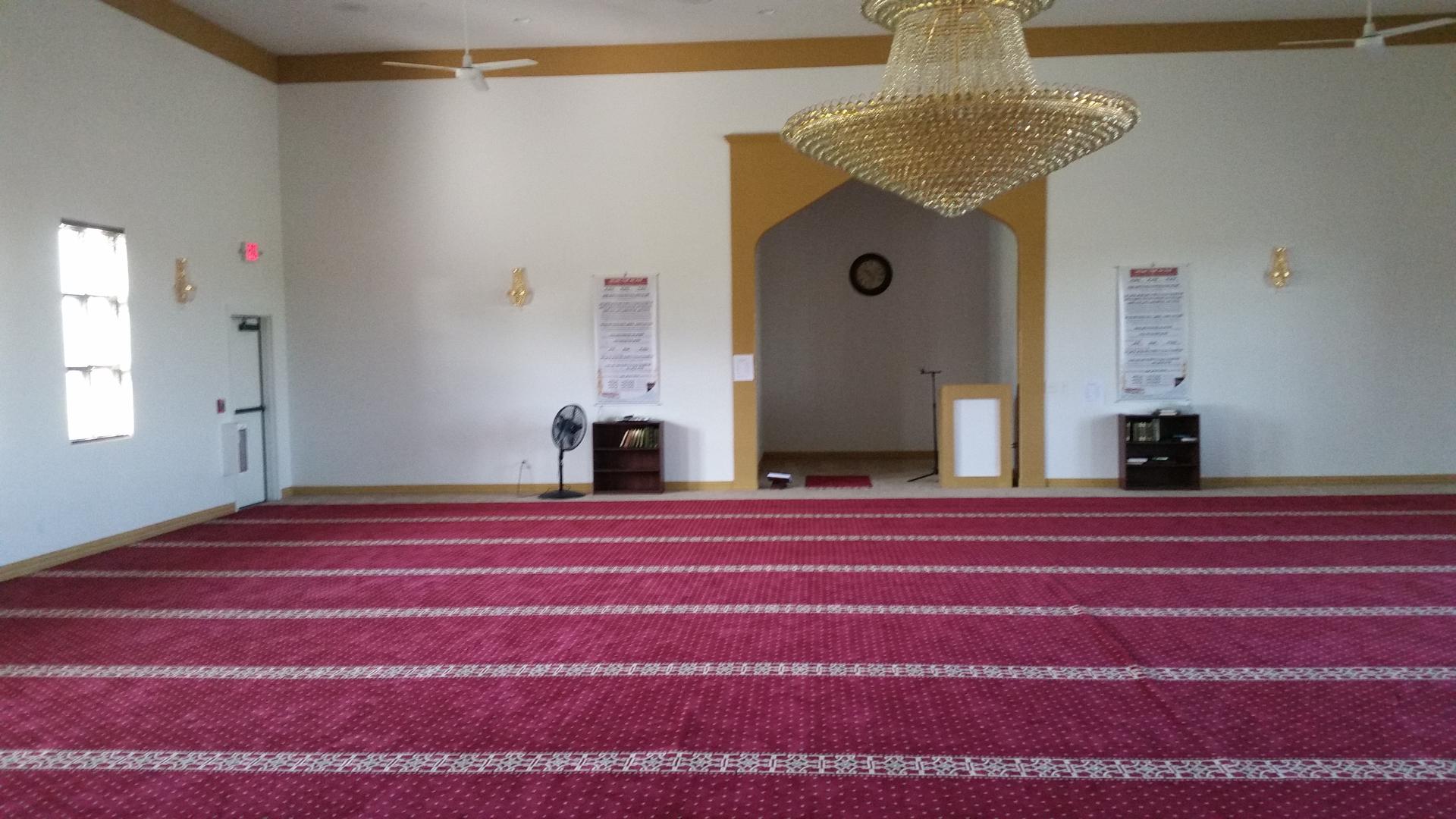

Today, Joplin’s mosque is housed in a plain building surrounded by a black gate and a fluttering American flag. One afternoon last month, kids were running around there, getting ready for an Arabic lesson. On the wall, posters explained the similarities between Islam, Christianity and Judaism.

Lahmuddin said on the day the new mosque opened, he felt deep gratitude. “Many of our Christian friends said that when God takes something from you, he will give you a better one. They believe in that. And we do, too. Now we have a mosque that’s better than the one that was burnt.”

The new mosque’s prayer space is a square room with wall-to-wall carpets. It’s big enough for at least 100 people — which might seem like more than Joplin needs. But this way, Lahmuddin said, there’s plenty of room for the community to grow.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?