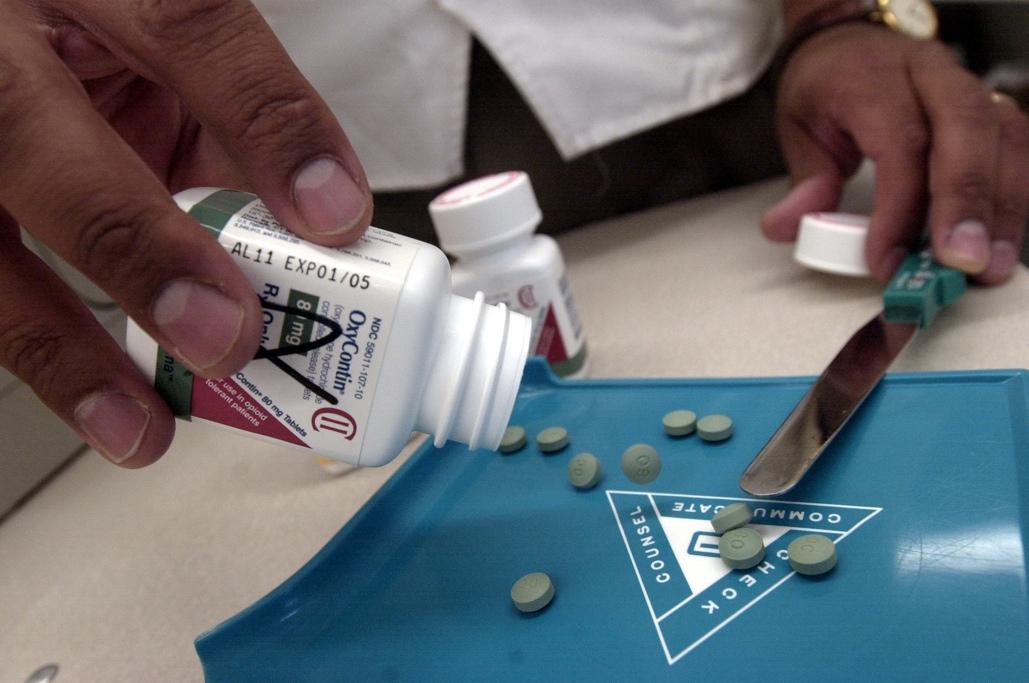

Canada uneasy about OxyContin phase-out

The powerful but addictive painkiller OxyContin is being phased out in Canada. But Canadians fear its replacement, OxyNEO will not be the answer.

HAMILTON, Canada — Canada is yanking the powerful, addictive painkiller OxyContin off its shelves, but the drug maker Purdue Pharma Canada's move to launch a substitute pill is not calming many nerves.

The pharmaceutical company has introduced OxyNEO as a replacement. Like its banned predecessor, OxyNEO contains the opioid oxycodone but the drug maker says it is harder to crush or liquefy it, and therefore more difficult to snort or inject.

OxyContin abuse is rampant in Canada, as a prescription drug and a thriving black market.

In the five years after OxyContin was introduced into the Canadian market in 2000, painkiller-related deaths shot up 41 percent — with over 300 deaths a year in the province of Ontario alone, according to a 2009 study by physicians at St Michaels Hospital in Toronto.

But perhaps the hardest hit are Canada’s First Nations people, the country’s indigenous groups — especially those living on remote northern reserves.

As many as eight out of 10 people were addicted earlier this year in the Cat Lake First Nation in northern Ontario, forcing the community to declare a state of emergency. Leaders there say they can no longer stem the social fallout from the drug or provide adequate care for those seeking help.

The Nishnabe Aski Nation, which encompasses 49 northern Native reserves, declared an emergency in 2009. As many as 10,000 members of their population remain Oxy-dependent, according to the community leaders.

More from Canada: Did botched police work enable the country's worst serial killer?

The small northern community of Sioux Lookout, population 25,000, also counts as many as 9,000 addicted to OxyContin.

Member of Parliament Dr. Carolyn Bennett criticized the government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper for failing to address the OxyContin issue properly. Swapping one drug for another would not suffice.

“The removal of OxyContin from the Canadian market threatens to exacerbate this problem, especially in northern and remote First Nations, some of which are already battling widespread opioid addictions,” said the federal Liberal Party Aboriginal Affairs critic, in a statement on her blog.

Several provinces, including Ontario and Saskatchewan — with the fastest growing rates of HIV infection in the country, which studies suggest in part is due to the high number of intravenous users of OxyContin — said they will put restrictions on OxyNEO.

Purdue Pharma Canada was “deeply concerned” about moves to limit access to their new product, it said in a statement last month.

“The restrictions to OxyNEO funding being imposed by some provinces are surprising. This product was specifically designed to help discourage misuse and abuse of the medication,” Purdue Pharma Canada said.

The statement indicated that the drug maker had been in talks with Canadian health authorities for two years planning the switch. However, Nishnabe Aski Deputy Chief Mike Metatawabin said his community only had two weeks notice to prepare for the changes.

Health officials are not convinced the replacement pill will work to stem addiction.

Read more: After Keystone pipeline, Canada's other oil project

“There is currently no evidence available to determine that these formulations lead to a reduction of prescription opioid abuse and abuse-related harm,” Health Canada spokesman Stephane Shank told the Toronto Sun.

The Harper government has mostly been quiet on the issue — something many of the impacted First Nation communities have complained about.

Concern is growing that First Nations communities will lack the medical care needed to treat the harsh pains of opiate withdrawal. Worse, some fear Oxy-users will switch over to heroin.

That concern might not be misplaced. Heroin production in Afghanistan, Canada’s main source of the drug, has grown 15-fold since 2001. Heroin seizures are up across Canada.

Erin Marie Daly knows too well the pain caused by opiate addiction.

Her brother Pat died from a heroin overdose in San Diego, California in 2009. But, she said, OxyContin was “his true love.” As the street price for Oxy increased and became more difficult to get, heroin took its place.

Daly, a San Francisco-based journalist, runs oxywatchdog.com, where she shares news about OxyContin and its abuse.

More from GlobalPost: Germany battles over future of solar

In April 2010 Purdue Pharma’s US branch also marketed a harder-to-break painkiller called Oxy P to reduce abuse.

San Diego’s chief medical examiner reported a spike in heroin-related deaths and a 300 percent increase in heroin use by area young people in the two years since Oxy P hit the market, according to San Diego television channel CBS8.

Daly said that for her OxyContin-addicted brother Pat, heroin was “waiting in the sidelines as a replacement high that was much cheaper … It was a natural progression for him.”

Back in Canada, frontline health workers servicing the remote northern communities believe it could be two weeks before the scale of the problem of withdrawal is truly felt here.