Lebanese women fight to overturn law that protects rapists

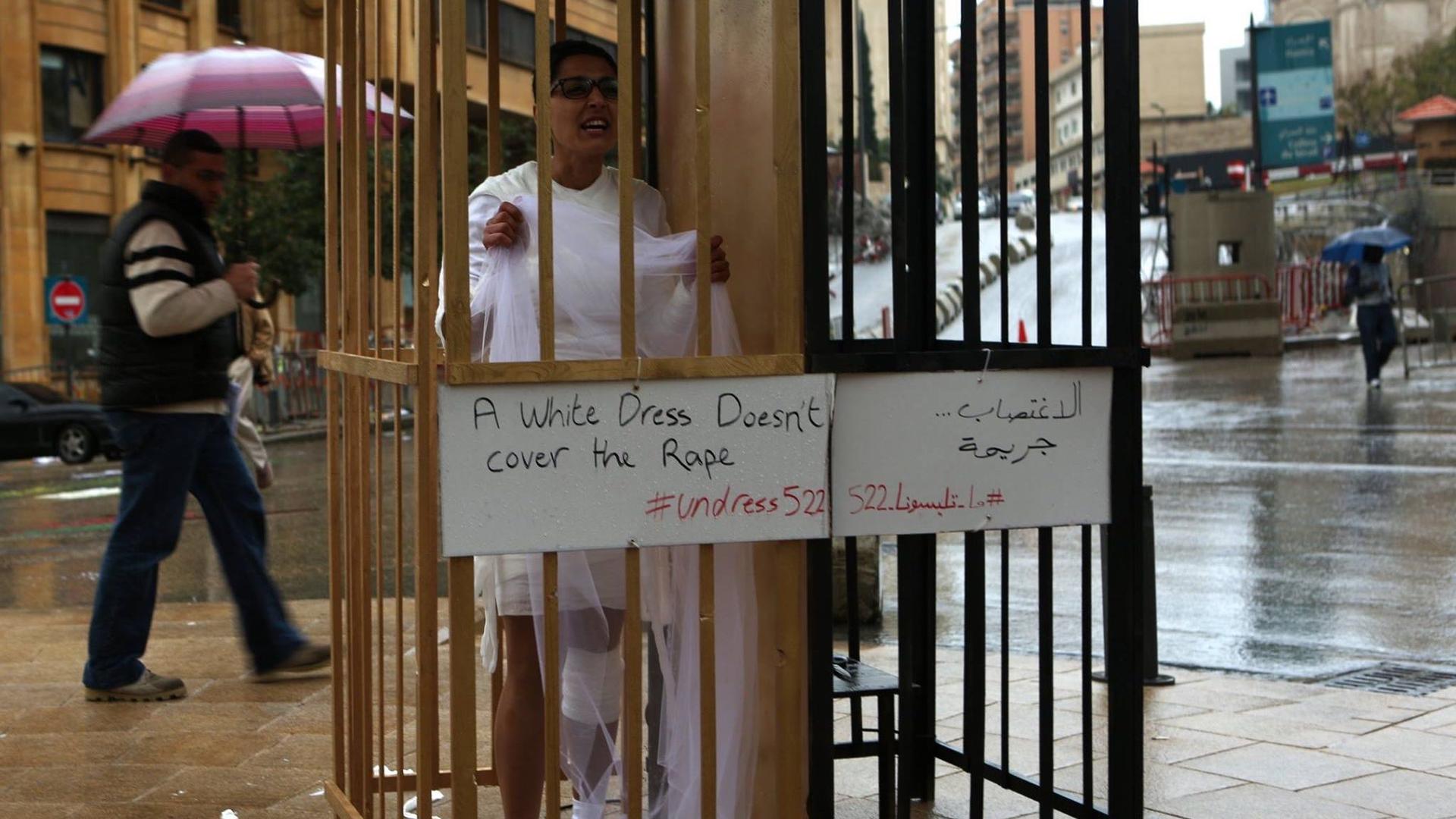

An ABAAD activist dressed as a bride inside a cage to protest against article 522 in the Lebanese penal code. The cage is split in half, the golden half symbolizing her imprisonment resulting from the law, and the dark empty half symbolizing the fate of her rapist.

A big vote is set to take place in the Lebanese parliament this week that could repeal a provision of the nation's penal code — article 522 — which states that men who rape women can walk free if they marry their victims.

Alia Awada, advocacy and campaign manager for the gender-equality group ABAAD, has been working to convince politicians and the Lebanese people that it's time to abolish the law.

“Usually when a woman gets raped, the men come and propose. The family says, ‘OK, it’s better for her to get married to him so she can live a normal life, and she will preserve her honor and the family honor,’” Awada says.

Awada and her group have started public information campaigns to spread the message that rape is a crime and that men should be sent to jail for sexually assaulting women.

“The second [message we sent] was that the woman has the right to say, ‘No, I don’t want to get married to the man who raped me once because if I get married to him then he will continue raping me my whole life,’” she says.

The group’s efforts have been successful so far.

“It worked at the policy level with different decision-makers,” says Awada. “The Justice Committee was studying abolishing the article 522 law. After this series of lobbying meetings, we managed to get this draft law discussed inside the parliament with different political affiliates, and the final voting will be this week, with hopefully a ‘yes’ to abolish article 522.”

Not overturning this law can have devastating effects, Awada says. Back in 2012, a 16-year-old Moroccan girl named Amina Filali killed herself after she was forced to marry her rapist. The backlash to her death lead to the repeal of Morocco’s rape-marriage law, article 475. Jordan and Egypt have similar laws, Awada says, but she argues the issue goes beyond legal statutes.

“The problem is not only the law, it’s all the practices and the traditions at the community level,” she says. “When we work on advocacy campaigns and public campaigning, we also work at the community level — we work with community leaders to say, ‘The law is not only the problem, but also our practices.’ When we start to change our mentalities and our practices, then we can achieve the change we want, not only in Lebanon, but in different countries.”

If the law is overturned, Awada and other advocates plan on focusing their efforts on cultural change so that women who are raped aren’t shamed or ostracized by their families and communities.

“We want to build this army of supporters who can help us to spread the message that rape is a crime, that women are survivors of this crime and that [female victims] didn’t do anything wrong,” she says.

This story originally aired on The Takeaway. It was produced in partnership with NewsDeeply.

Correction: A previous version of this story misspelled the name of Alia Awada. It has been corrected.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!