How Washington ranchers are learning to cope with wolves, with lessons from Uganda

Rancher Bill Johnson and wildlife researcher Carol Bogezi are pictured, here, on Johnson's ranch in Washington's Teanaway Valley. Bogezi has been working with Johnson and other ranchers in eastern Washington to try to find a way to help them live more amicably with wolves.

Bill Johnson lives with his seven border collies in a log house that he built himself in the Teanaway Valley, just over the Cascade Mountains that divide rural eastern Washington state from the more urban western part.

Johnson’s been a cowboy here for about 16 years. When he started, there were no wolves around, but that changed about five years ago. He vividly remembers his first encounter with the returning predators.

He was driving out of the valley one night when a deer ran across the road.

“And these three large German shepherds ran across after the deer,” he says. “And I’m thinking, ‘Those aren’t German shepherds, those are wolves. … Those are wolves! Can you believe it?’”

A month later, the return of wolves to the area really hit home. Johnson was out with his dogs when one of them — Lance — disappeared.

“Lance went off on his own and by the time I realized he was gone, it was too late,” Johnson says, his voice cracking and his eyes tearing up. It was the first animal he’d lost to a wolf.

That night, Johnson saddled his horse and grabbed his gun.

“I was going to kill every wolf in the Teanaway,” he says.

Johnson says a lot of ranchers in eastern Washington feel the same.

“There are ranchers who operate on the premise that ‘the only good wolf is a dead wolf,’” Johnson says. “When the wolves first came here, their vision was that the wolf pack was going to run rampant through the Teanaway Valley and kill all the elk and all the deer, and then start working on the horses and the llamas and the cattle, and eventually they would start pulling children out of the sleeping bags at night.”

It’s a common fear around here. Wolves had been unknown in Washington since the 1930s when they were largely eradicated.

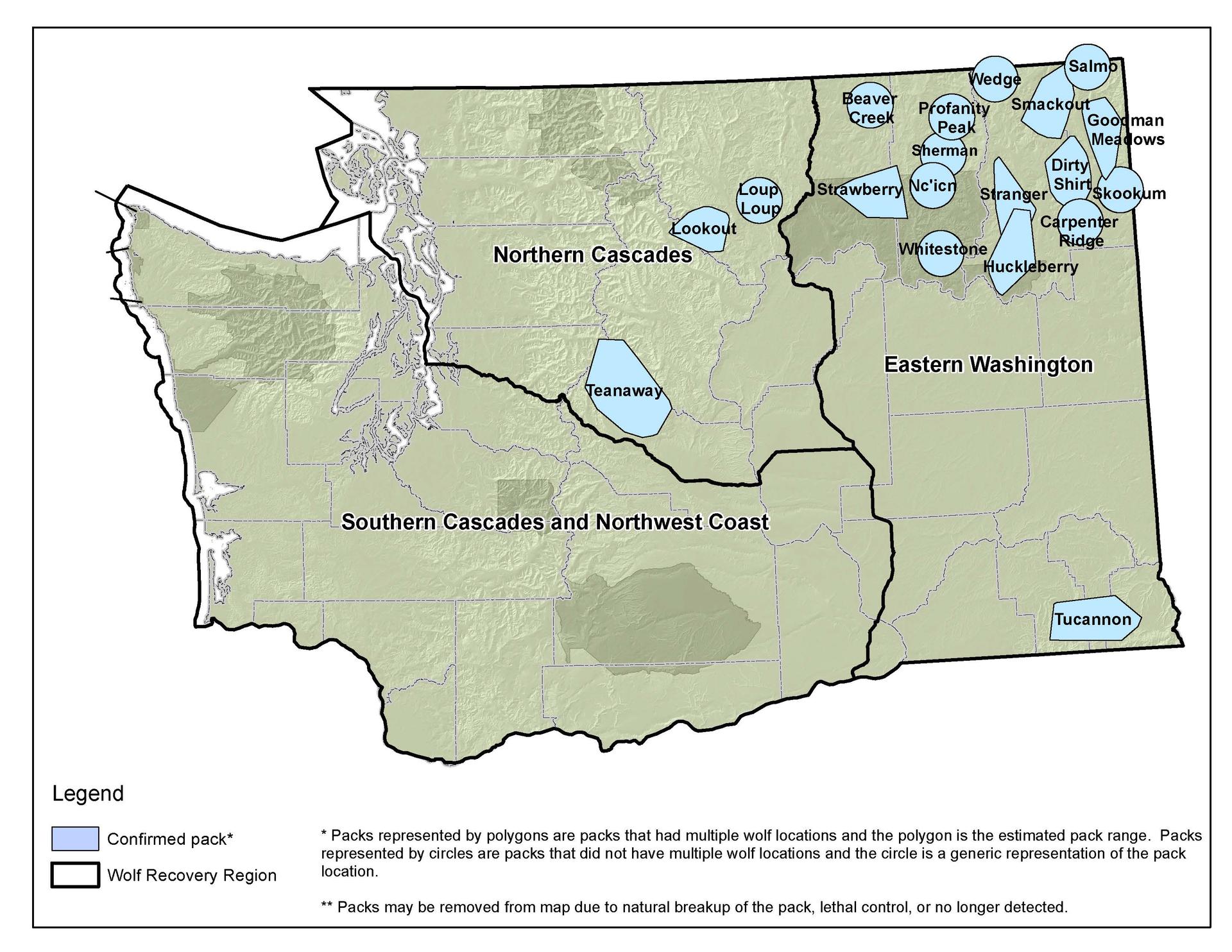

But since 2008, Washington's wolf population has gone from zero to nearly 100, as wolves began moving back to the state from longstanding populations in Canada and reintroduced populations in the northern Rocky Mountains.

Conservationists have championed the return of wolves to some of their original territory as vital to healthy ecosystems. But many ranchers and other rural residents see the animals as a threat to their way of life.

It’s not an abstract fear. Since the first wolves returned, they’ve killed at least 27 cattle.

The state generally protects the animals, but it does have a policy of culling any pack in eastern Washington that kills more than four cattle.

It also offers to compensate ranchers for animals lost to wolves, but it turns out that ranchers don’t much like that idea.

“With compensation, someone comes in and you have to write [everything] down, and it’s like you’re begging for this money,” says Carol Bogezi, a researcher at the University of Washington in Seattle. Bogezi’s been talking about wolves with ranchers and cowboys like Bill Johnson for the past two years, enough time to know how many of them they feel.

And getting to know them well has been key to her work here: trying to find ways to help rural residents become more accepting of wolves.

The effort starts with the choice of attire for her conversations: a checked flannel shirt.

And she says she starts every interview in the same way: “I’m not even from Seattle,” she tells each rancher, “so I won’t be telling you what to do!”

“Not from Seattle.” It's a big icebreaker in these parts. For many folks in eastern Washington, Seattle represents the urban elite, people who like to pontificate about what others should do but have no idea what life elsewhere is really like.

And Bogezi is, indeed, not from Seattle. She grew up in Uganda on her family’s small farm outside the capital Kampala. But she says she understands the ranchers’ perspective because her family had problems with predators, too — things like civet cats and monkeys that would eat her family’s chickens, sheep and goats.

It was her job to shoo the predators away during the day. At night, the family hired someone to take more lethal action.

Bogezi would sometimes find a dead predator in the morning.

“It was heartbreaking,” she says. “You don’t want them to be eating the lambs or baby goats or chickens, that’s tough, but then also finding a dead civet cat felt sad.”

Bogezi says her family thought she’d outgrow her love of predators, but she didn’t. After college in Uganda, she worked with crocodiles before getting a scholarship for grad school at the University of Washington.

At UW, she’s studied a range of possible solutions to Washington’s wolf conflict. The one she thinks would work best is a wolf-friendly meat certification program, in which ranchers who do their best to minimize conflict would be able to sell their meat for a premium in — ironically— places like Seattle.

There are a couple of reasons it could work, she believes.

“Once a market incentive takes off,” Bogezi says, “it pretty much is regulated by the laws of economics, which ranchers really mostly like to work with.”

And places like Montana have already tried out similar programs, so “it’s also not a very novel thing in the West,” she says. “You don’t have to start from scratch."

Bogezi recently won a fellowship from the Seattle-based Bullitt Foundation that will help her study the certification idea from the consumer side, to see how much people might be willing to pay for wolf-friendly meat.

After that, she hopes to start a trial run of such a program.

Rancher Johnson was skeptical of the idea at first. But he says his talks with Bogezi helped change his mind about living with wolves.

“Once the anger and the grief was gone, it was a natural process,” Johnson says. “You take somebody swimming in the ocean, there’s a chance they get eaten by a shark. The wolves came back — they’ve basically wandered back into their homeland — and so we’re going to get along. We’re going to make it work.”

If it does work, Bogezi says it may be partly because of her role as an outsider — not just from the other side of the mountains, but from the other side of the world.

“Because what happened here, is, I have to listen more. I have to make sure I understand,” she says. “And I think that’s a great skill to have when you’re going to be working with communities about wildlife or other natural resources which they may not think of as the most valuable thing."

It’s a skill that Bogezi eventually hopes to bring back to Uganda, as well. When she has finished her work here, she wants to go home to work on preventing conflicts between people and elephants.