This 13-year-old girl says soldiers in Myanmar gang-raped her and torched her village in a brutal ethnic cleansing raid.

For Fatima, a 13-year-old girl from Myanmar’s western marshlands, the new year began with a grueling escape. She spent the first days of 2017 on the run, slogging through rice fields in the dark.

With each step, cold muck sucked at her ankles. The sky above was dark — just a dim crescent moon and a thousand pinpricks of starlight.

She was grateful for the blackness of night. At least there was no sign of armed border guards on the horizon. No distant flashlight beams scanning for intruders in the fields.

She was determined to stay alive until she reached the refugee camps in Bangladesh — a haven for Rohingya Muslims, among the world’s most tormented people.

But as Fatima trudged on, her insides burned. Just one week before, Myanmar’s army had violated her in almost every imaginable way.

It happened on Christmas Day. A platoon stormed into her village, torching homes and rounding up Muslims. When she tried to escape, Fatima says, three soldiers tracked her down and raped her, repeatedly, in front of her sobbing mother.

“My mom watched everything,” Fatima says. “What could she do? They are the army — and she’s just one lady.”

Fatima blacked out from the pain. When she awoke, her charred village was unnervingly quiet. The soldiers were gone and everyone had fled — even her parents. She was feverish, alone and bleeding badly.

Fatima thanks God for the strangers who discovered her. All around her district, other villages were also under siege — and a few adults, escaping their own hell, happened to pass by her home.

“They said, ‘You can’t stay here. You’ve got to come with us. We’re fleeing to the camps in Bangladesh.’”

Fatima joined the group on its journey to the border. After several days of plodding through rice fields, they arrived at their destination: Kutupalong Refugee Camp.

It is a grim colony, full of heartache and sickness. Fatima was just another newcomer caked in paddy muck. Fresh arrivals are directed to the camp’s perimeter, a place where refugees must sculpt their own shelters out of mud and plastic sheeting.

Miserable as it may be, the camp’s population keeps swelling — perhaps north of 80,000 people. Each day, Rohingya show up with horror stories. The men speak of flaming villages. But even darker stories are told by women and girls. They are subjected to a distinct form of cruelty.

A walk through Kutapalong Rohingya refugee camp

A video posted by Allison Joyce (@allisonsarahjoyce) on

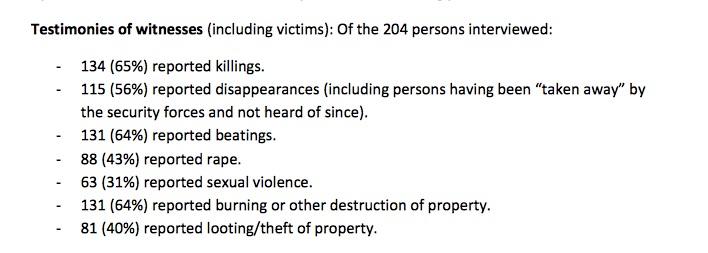

Practically every major rights agency — from the United Nations to Amnesty International to Human Rights Watch — has interviewed scores of these women.

Fatima’s nightmare is not unique.

Myanmar’s troops are systematically raping Muslim women — a tactic seemingly designed to terrorize this population into fleeing the country.

It is alarmingly effective.

*****

Since October, nearly 70,000 Rohingya have poured out of Myanmar into neighboring Bangladesh. Add that figure to the 300,000 to 500,000 Rohingya refugees who’ve fled purges in decades past.

That’s a population the size of Belize or Luxembourg, all exiled from their homeland.

This is 21st-century ethnic cleansing, orchestrated by Myanmar’s army. It is abetted by the government, now helmed by Aung San Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize winner who rose to power with American backing.

The military’s prime goal, it seems, is to make life so intolerable for the Rohingya that they leave Myanmar forever.

Among Myanmar’s Buddhist officialdom, Rohingya Muslims are often portrayed as an invasive species.

One state-run newspaper suggests they’re “human fleas … loathe for their stench and for sucking our blood.” A prominent lawmaker refutes their rape claims by insisting Rohingya women are too “dirty” to arouse soldiers.

If only this was all talk. For years, the state has imposed a complex system of apartheid upon Myanmar’s roughly 1 million Rohingya. About 10 percent are held in internment camps. The rest are quarantined in militarized districts and forbidden to travel.

In any given year, these hardships will pressure a stream of Rohingya to escape the country. Some sail east on creaky boats bound for Malaysia. But most go west, across a wide river into Bangladesh.

As the army rampages around Myanmar’s coast, that stream has become a torrent of people — all surging toward refugee camps.

Even UN officials, who typically prefer bland assessments, are calling this “ethnic cleansing” and a “process of genocide.”

Other high-profile observers go much farther. More than a dozen Nobel laureates liken this crisis to past horrors in Darfur, Bosnia and Rwanda.

The laureates are pleading for a credible investigation into the rapes and killings. Among them: Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai — a teenage Muslim girl, just like Fatima.

These peace-prize winners warn that “if we fail to take action … people may starve to death if they are not killed with bullets … which will lead us once again to wring our hands belatedly and say ‘never again.’”

*****

Kutupalong Refugee Camp is surrounded by an ochre moonscape. You enter the camp by climbing bald hills of orange dirt. In the valleys below, rainwater accumulates in viscous, malarial ponds.

Keep going and you’ll reach a labyrinth of clay dwellings. This is the camp’s raucous core — a grid of dirt lanes, inhabited by naked kids and underfed adults.

I’m here to interview Fatima. I’ve brought along a female Bangladeshi colleague — just in case Fatima prefers to direct her answers to a woman instead of a man.

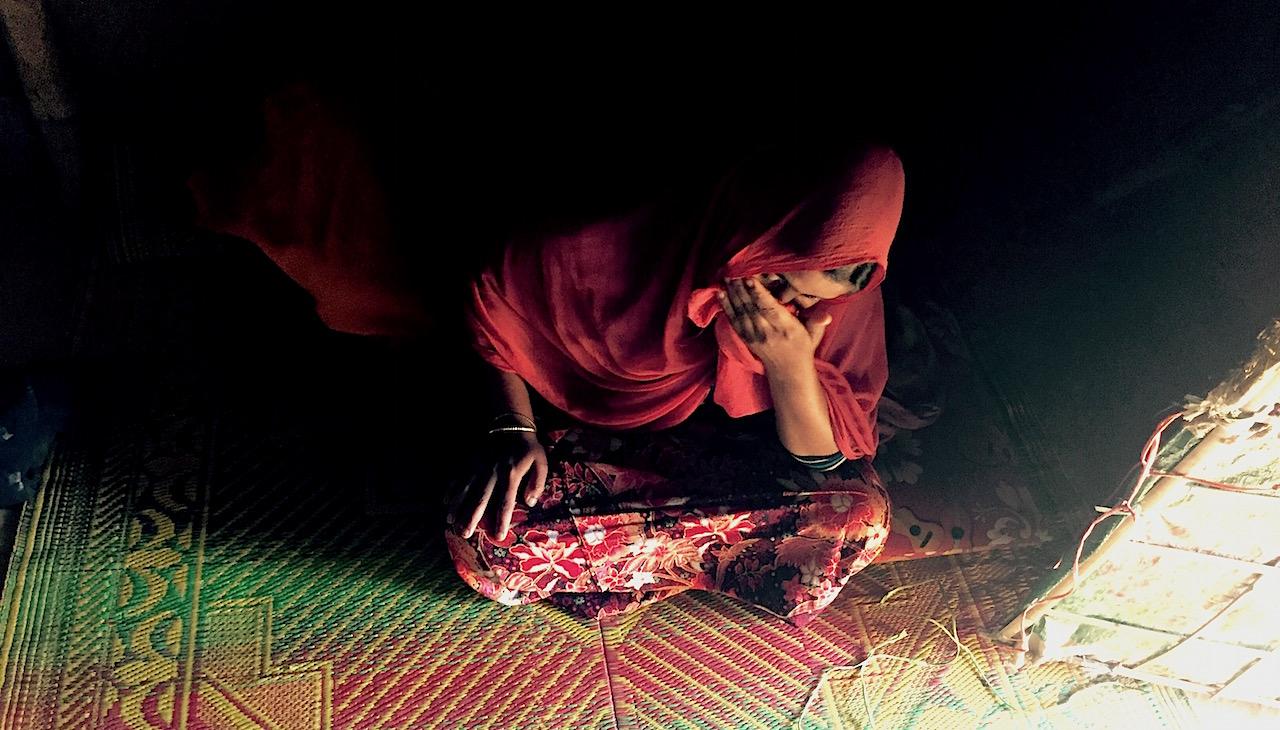

Fatima waits for us inside a one-room shelter. Its door is a rectangular scrap of tin. Inside, a few female Rohingya elders have cleared out a private space, a semiquiet spot where we can speak to Fatima under their supervision.

When this meeting was first arranged, the elders conveyed that we’d be speaking to a woman — a recent victim of army violence who’s keen to share her story.

But when that tin door clatters open, and daylight illuminates Fatima’s childlike frame, I can see that she’s not a woman at all. She’s barely even a teenager.

We find Fatima sitting cross-legged on a plastic mat. She’s swaddled in a floral print dress. Tufts of dark hair peek out from her bubble-gum pink hijab. She projects a stark solemnity that should not be emanating from a child’s eyes.

Fatima isn’t her real name. It’s a pseudonym to prevent retribution against her family, wherever they may be. In fact, there are many details of her story that I cannot independently verify.

Shoring up each claim would require venturing to her village, which lies in Myanmar’s swampy Maungdaw District. This is a conflict zone sealed off to almost all foreign aid workers and objective media. One genocide research team refers to this zone as an “information black hole.”

However, I have managed to corroborate much of Fatima’s account through various eyewitnesses, Bangladeshi officials and health care workers.

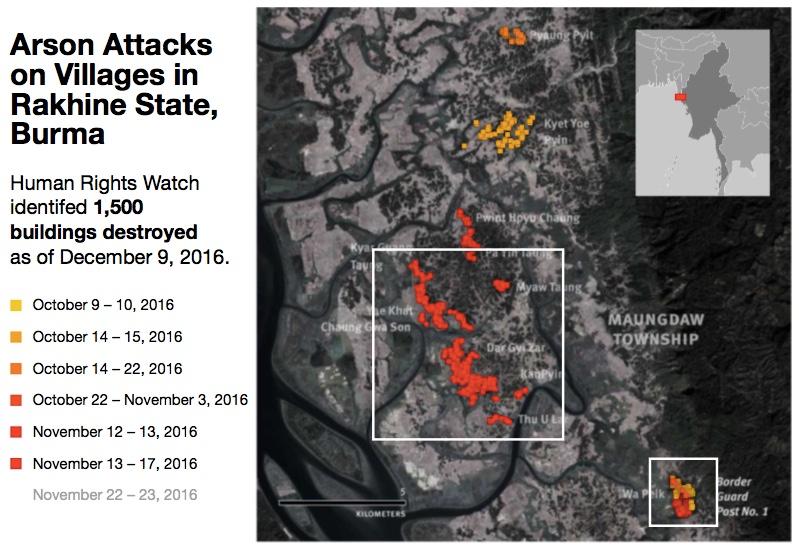

Satellite photos confirm that her home district, Maungdaw, is indeed scarred from an army-waged arson spree. From cameras in space, thousands of wooden homes now appear as ashen blotches.

But none of this is as compelling as testimonials from Rohingya women and girls who’ve also escaped sexual violence. In addition to Fatima, I found three other women and girls who fled army raids in the same district.

The scale of this rape offensive is astonishing. Roughly half of all female Rohingya refugees interviewed by the UN say they were recently raped or sexually assaulted by Myanmar’s security forces. Among these cases, gang rape is obscenely common.

Worse yet, the UN believes “embarrassment and stigma” are driving down reports of the crimes — thus presenting an “underestimation” of the rape campaign’s pervasiveness.

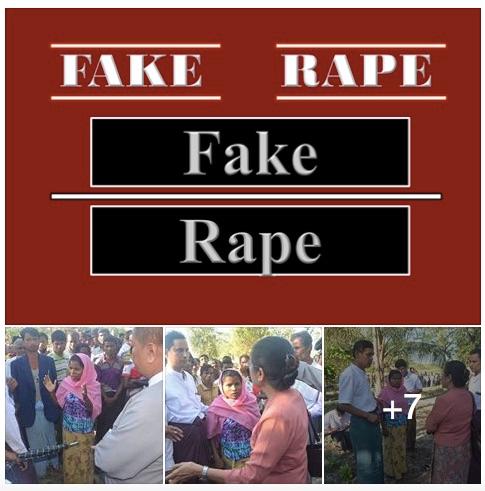

In the face of overwhelming evidence, Myanmar officials have clung to a claim that, somehow, all of these women are lying.

“It’s absurd,” says Matthew Smith, founder of Fortify Rights, perhaps the most active rights organization documenting crimes against the Rohingya.

“It would take an absolutely profound amount of organization to control the messaging of thousands and thousands of civilians who have lost everything,” he says. “They are clearly, severely traumatized.”

The government wants the world to trust an alternate narrative presented by its own state-sanctioned investigation commission. But that’s a tough sell. The man chosen to lead this commission? His name is Aung Win — the same lawmaker who thinks Rohingya women are too “dirty” to rape.

Meanwhile in Bangladesh, refugees with rape injuries keep turning up in medical clinics — each woman a living refutation of the state’s denials.

*****

Hundreds of eyewitnesses and victims such as Fatima, plus video evidence, indicate that Myanmar troops and police aren’t merely running amok. When raiding Rohingya villages, platoons appear to follow a playbook.

Step one: Accuse villagers of aiding extremists

In Fatima’s village, the soldiers “came around 10 p.m., appearing out of nowhere,” she says. “They said our village is supplying food to militant groups.”

This is the grand pretext to the overall purge. Officially, these raids are called “clearance operations” to flush out “extremist individuals.”

This rationale hinges on a scrap of truth. In October, a Rohingya militant group emerged on YouTube to call for an armed uprising. Its debut attack struck three police outposts. The militants, armed with knives and slingshots, killed nine officers and looted a trove of rifles.

It’s possible, of course, that this militant cell could grow into a fearsome organization. It is coordinated by Rohingya emigrants in Saudi Arabia, according to the International Crisis Group.

But for now, the militants seem to be sickly and scattered. They have mounted no major attack for months.

Even the army admits that these “terrorists” often amount to guys with sticks and farm tools rushing suicidally at armed squadrons. Some have acquired guns — but they look like antiques from the 18th century.

This poorly armed group — commanding a few hundred men at most — has not liberated 1 inch of soil. But they’ve given soldiers a perfect excuse to prey on the other 1 million Rohingya.

Step two: Torch homes, destroy property

At least 1,500 buildings in Rohingya-populated areas have been destroyed, according to satellite images commissioned by Human Rights Watch.

The real figure is likely much higher. Tens of thousands of refugees have fled arson attacks since November, when that estimate was presented. And more than half of all recent refugees interviewed by the UN say their own homes were torched.

“They didn’t just burn down houses,” Fatima says. “They grabbed the old men and tried to burn their beards off. They even shot our goats.”

Step three: Segregate the genders

Once a siege begins, villagers are often corralled into two groups: one for men, another for women.

This tactic — dividing the genders — has been reported by hundreds of escapees. It’s also evidenced by a mobile phone video, grudgingly verified by the government.

In the clip, police are seen rounding up about 100 Rohingya men, segregating them from the women. They force them to sit in the dirt — and then start kicking them in the face.

“This is actually the least violent type of abuse we’re documenting, appalling as it is. In a number of cases, soldiers have slit the throats of Rohingya men,” Smith says. “We’ve also received reports of babies thrown into fires.”

Warning: The following video shows graphic violence by Myanmar border police against Rohingya.

Fatima doesn’t know what happened to the women who were corralled in her village. At that point, she was hiding inside her family hut. She was discovered by three soldiers, who stripped her down and searched her body for gold. Then they took turns raping her.

Another woman from a nearby district — Noor, a 26-year-old mother — told me what happened after women were rounded up in her village.

“The soldiers pick out women who are young and beautiful,” Noor says. “They don’t care if you’re married or not. They don’t even care if your mother is watching.”

“From the larger group of women, they chose me and three others. All of us were raped. I didn’t want to allow this … but I watched them slit the throats of two women. I thought that, well, if we sacrifice ourselves in this way, at least we’ll enter jannah.” (Jannah is the Islamic conception of paradise.)

“You know, even if I was a man, I couldn’t have fought back,” Noor says. “All of us are helpless against the army. If you’re Rohingya, it hardly matters if you’re a man or a woman.”

Step four: Drive out the population

This is the natural outcome of all this death and arson. Homeless and humiliated, the Rohingya run for the border.

Throughout its history, the army has relied on mass rape to traumatize non-Buddhist populations. All of these stories will sound eerily familiar to Christians living in Myanmar’s remote eastern jungles.

But perhaps no group in Myanmar is reviled quite like the Rohingya. One political faction in Myanmar has for years stated that “inhuman acts may be justifiably committed” to eliminate them.

Even in Suu Kyi’s party, the Rohingya are derided as non-native “Bengalis” who don't belong in Buddhist Myanmar.

As for Suu Kyi, the state counselor and de facto leader?

She is not merely indifferent to Rohingya suffering. She now oversees a propaganda machine that works to silence their pleas for help.

*****

These days, the world’s attention is hoovered up by Donald Trump, Brexit and other right-wing phenomena swirling through the West. But this fixation is obscuring what — in a less scandalized time — might go down as one of the stranger twists in global politics.

Prim and Oxford-educated, Suu Kyi is the most famous person from Myanmar to have ever lived. She is among the world’s most celebrated former political prisoners — a name mentioned alongside Nelson Mandela.

For decades, the West has lionized her as a defender of the meek. Her ascent to power, in a historic 2015 election, was secured with the help of US and UK sanctions.

Just a few weeks before the Rohingya purge began, Suu Kyi was invited to the White House to “celebrate progress” in her fractured nation.

But the American and European diplomats who’ve crusaded for Suu Kyi must now contend with an unsettling truth. In a darkly ironic turn, this icon of nonviolence and freedom has become deeply complicit in ethnic cleansing.

“I think a number of people around the world created a version of Aung San Suu Kyi that may not exist,” Smith says. “At this point, it’s safe to say she’s part of the problem.”

The most charitable view is that Suu Kyi is powerless to stop the army.

Indeed, the Myanmar military — one of Asia’s most notorious — does not answer to Suu Kyi. Under a power-sharing arrangement, she commands the nation’s politics, not its platoons.

But that doesn’t fully explain why her government is restricting foreign aid to Rohingya-populated areas. Nor does it atone for her office’s propaganda campaign, which issues fantastical claims.

Her offices contend that Rohingya torch their own homes to wring pity out of foreigners. They insist that soldiers always obey the law. They accuse Rohingya women of fabricating rape tales.

The state has even taken to using Trump-esque rhetoric — “fake news” or even “fake rape” — to dismiss media reports.

Diplomats are losing patience. “I find it quite incredible that these desperate people are willing to burn down their own houses … just to give the government a bad name,” says Yanghee Lee, a UN special rapporteur.

“The government’s response to all of these problems,” Lee says, “seems to currently be to defend, dismiss and deny.”

In recent months, Suu Kyi has retreated from both domestic and international press. (Her spokesman did not return repeated calls seeking comment.)

But in December, speaking to Singapore’s timid state-owned media, she scolded the “international community” for “always drumming up cause for bigger fires of resentment.”

“It helps if people … are more focused on resolving these difficulties,” Suu Kyi said, “rather than exaggerating them so that everything seems worse than it really is.”

*****

These official statements present an implausible view — that these half-starved refugees are masters of disinformation, tapping some sort of hive mind to coordinate a campaign of lies.

It’s much harder to ascribe such an agenda to doctors in Bangladesh. Quite a few are fatigued with the penniless Rohingya who show up in their emergency rooms with sexual assault wounds.

“Bangladesh is exhausted with the Rohingya,” says Akhtarul Islam, the assistant director of Cox’s Bazar District Hospital. His medical center is one of several that reluctantly takes in refugees.

“You know, we’re an overpopulated country. We have our own problems,” Islam says. “But they’re human. So we have to treat them.”

Conversations with various hospitals and clinics in eastern Bangladesh indicate that, since the attacks began in October, medical workers have seen a spike in refugees with severe rape injuries.

This spike is hard to quantify. One medic who works with refugees tells me he’s documented more than 100 allegations of rape implicating Myanmar troops. At another facility — Fouad al-Khateeb Hospital in Cox’s Bazar — an administrator says he’s seen roughly a dozen cases in recent weeks.

“We only get eleventh-hour cases, Rohingya patients with critical lower abdomen injuries,” says Syfuddin Khaled. “We don’t ask what happened to them. Sometimes they tell us anyway.”

Doctors are not inclined to report a rape that will get some undocumented woman caught up in the legal system — especially when the alleged rapist is in a different country.

“You have to consider that, if we know about a rape case, we’re supposed to inform police — and these women are not here legally,” Khaled says.

A mélange of factors, from shame to poverty to fear, can pressure Rohingya victims of rape to keep quiet — especially those who aren’t severely injured. Even if there were a central agency collating these cases — and there isn’t — many rapes would go unreported.

Hours after talking with Fatima, I contact a 45-year-old medic who works in Kutupalong Refugee Camp. We arrange to meet nearby, inside the van I’ve hired to get around.

Parked by the roadside, the van should offer a little sanctum of privacy away from the clamor of the camp. It is quiet here, a stillness punctuated only by passing trucks and crickets chattering in the shrubs. In the distance, across the road, I can see a sparse tree line. This marks Kutupalong’s outer perimeter. I can faintly make out silhouettes peering over through the foliage.

Around 8 p.m., the medic slides open the van’s side door. His name is Boktoo. He is bearded, clad in beige robes, and thoroughly exhausted.

Boktoo operates a mobile clinic for refugees. It is unglamorous, terribly paid work. And since the purge began, he says, it has been unrelenting.

“What I’m seeing is horrible,” he says. “I’ve even treated elderly women for rape. Lots of teenage girls. Often they don’t want to say exactly what happened — especially if they’re unmarried. They want to preserve their future.”

Since October, when the army raids began, Boktoo has tried to tally every case of sexual violence reported by an incoming refugee. His tally so far? “More than 100,” he says. It’s an astounding figure — and one I can’t possibly verify.

“I have some proof,” he says. As Boktoo fishes a smartphone from his robe, I notice that the silhouettes by the trees are now moving closer, their bodies lit by passing headlamps.

“Look at these videos,” he says. What follows is a gory series of clips, each one bloodier than the next. They feature patients who, according to Boktoo, require emergency treatment for rapes committed by Myanmar troops. Overwhelmed, he refers many cases to a Doctors Without Borders clinic nearby.

“I filmed this myself,” Boktoo says. “So how can anyone tell me this is fake?”

We are startled by a tap, tap, tap of fingernails rapping against the van’s windows. Boktoo and I twist in our seats. There are a dozen or so veiled women outside, noses pressed to the glass, begging for food with cupped hands.

“See? These women get abused in Myanmar,” Boktoo says. “They end up like this. Out in the cold, totally vulnerable.”

*****

The two-lane highway by Kutupalong camp has become a gauntlet of outstretched hands.

Day and night, refugee women huddle by the asphalt shoulder. Clad in colorful abayas, they squat under the trees, holding out their palms, gazing up at traffic with hungry eyes.

Fatima has not been reduced to this fate. Soon after her arrival, the girl was hustled over to that Doctors Without Borders clinic near the camp. Doctors spent days treating her internal injuries and lowering her fever.

“It felt strange with no parents, no relatives beside me,” Fatima says. “I felt helpless.”

But recently, Fatima regained a family of sorts. In fact, the 13-year-old is now married to a man who is more than double her age.

When Fatima reveals this, I’m baffled. Less than three weeks ago, this girl walked into this place bleeding and slathered in mud. How the hell did she wind up in a marriage?

I ask Fatima to introduce me to her husband. “Sure,” she says. “I’ll show you where we live.” She leads me to a windowless clay hovel. Its roof comes up to my chest.

“So this is my house,” Fatima says. “Though I would not call this a house exactly.” To Fatima, it’s more like an animal pen.

Stooping low, we crawl inside. The interior is dark as a crypt. Each night, Fatima sleeps here on a cement floor — sharing a plastic mat with her new husband and a woman she now regards as a surrogate mom.

This surrogate, herself a Rohingya refugee, discovered Fatima bedridden in the clinic. She feared the girl would be released into the camp and preyed upon, once again, by wicked men. So the woman badgered her younger brother into an emergency marriage with Fatima.

I find the husband — Nur, 28 years old — idling outside the house. He’s a thin, shaggy-haired guy in a dust-caked polo shirt. Marrying this orphaned child, he tells me, will be regarded by God as a charitable deed.

“Yes, it was my sister’s idea,” he tells me. “We felt terrible that the army did this to her. So I married her, as a sacrifice to Allah, to obtain blessings in the afterlife.”

Seventeen mornings ago, back in Myanmar, Fatima opened her eyes in the little bamboo cabin where she was raised. She was ensconced in the warmth of family.

She had a simple life, revolving around household chores, set to the rhythms of the rice fields. Rohingya society is deeply conservative so, like most teenage girls in her district, Fatima’s world was kept very small. Even married women seldom stray far from the house.

Now Fatima is stranded in a foreign land, wed to some unfamiliar man, her head filled with hideous memories. “The soldiers had no right to do that to me,” Fatima says. “My anger will never go away.”

She is possessed with an urge to flee back across the marshy flatlands — back into the maelstrom of flaming huts and uniformed predators. Back to a country run by people who think she’s a human pest. Back to the only home she knows.

“If I return,” Fatima says, “I’m quite sure the military would try to kill me. But I must find my parents. Maybe Allah has taken them away. But if he kept them alive, I’ll surely find them.”

“I think I can face this,” Fatima says. “After what happened in my village, I’ve become like a grown woman — a person who has seen things. So many, many things.”

Essential reporting for this story was provided by Muktadir “Romeo” Rashid, a Bangladesh-based journalist.