2016 brought more record temperatures. So what climate course will the US and Trump set in 2017?

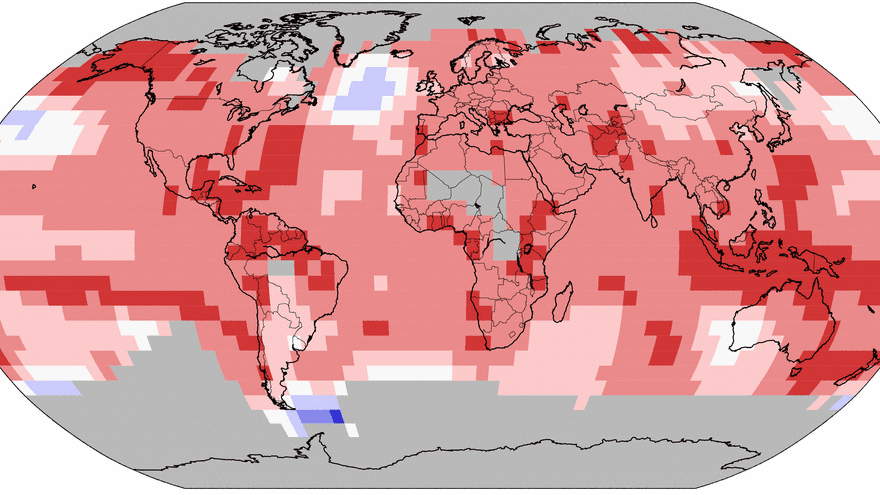

After an extremely warm first half of the year, global surface temperatures were heading for a third-straight record warm year in 2016. This NOAA map from December shows record warm temperatures (red) and record cold (blue) through the first 11 months of the year.

It's all but official — 2016 will almost certainly go into the books as the warmest year on record. If that sounds familiar, that's because it's the third year in a row we're saying it.

It's hard to argue anymore that the planet is not warming up fast, and that we're not quickly heading into very dangerous territory. Unless, that is, you're part of the incoming US administration. President-elect Donald Trump, and the people he's named to key positions, largely dismiss the threat of climate change and the mountains of science behind it.

And they're in a very strong position to influence how the world responds to the climate crisis. So what will a Trump presidency mean for climate policy and climate reality in 2017?

It’s a tricky question. We have no crystal balls here at The World of course, just the record of what’s happened and what Trump has said and done so far.

But staying well connected to the facts as we know them, The World’s Marco Werman sat down for an interview with the show’s eyes and ears on all things climate, environment editor Peter Thomson. Here's an edited version of their discussion.

Marco: So it's look-ahead time for 2017, Peter. What do you see?

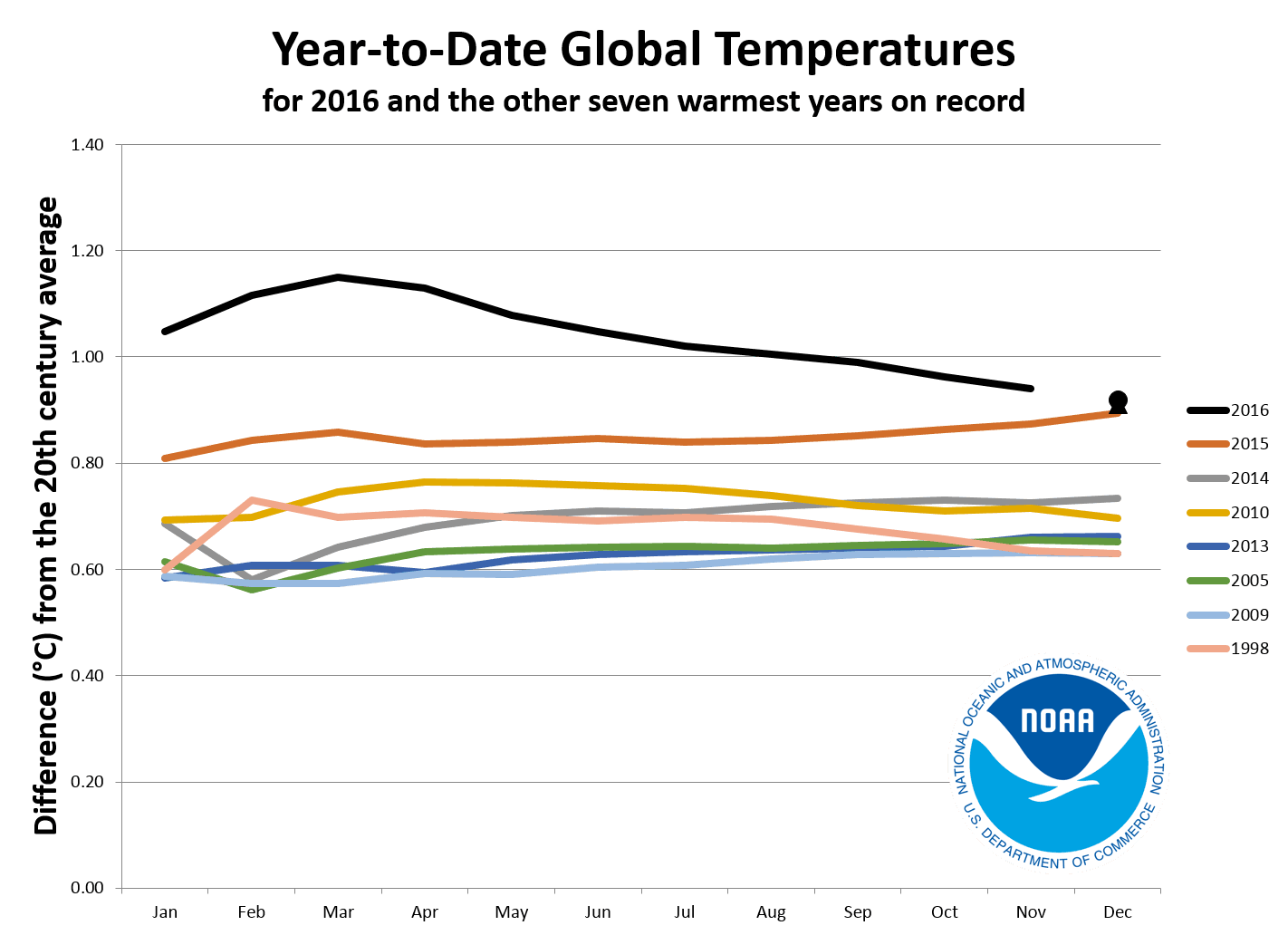

Peter: Well, to begin with the planet’s going to keep getting warmer, and over the next 12 months at least, Donald Trump will have nothing to do with that. We’re in the middle of a warming trend that’s unprecedented since records were first kept back in the 19th century. According to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) through 2015, the five hottest years on record have all occurred since 2010, and the 16 hottest have all occurred since 1998. Researchers say 2017 might be a little cooler than 2016 but the trend is clearly up, up, up, with all the dangers that brings — rising sea levels and coastal flooding, bigger heat waves, droughts and downpours, more disruption in food supplies, and more people displaced by all of it.

Of course 2017 was the year that the world was actually supposed to start getting serious about taking on the climate crisis. The landmark Paris climate accord was adopted a little more than a year ago, it went into effect last fall, and that set up 2017 as the year that virtually every country in the world was going to start making the changes that would start bringing climate pollution down to less dangerous levels.

But now with Trump heading to the White House, that's all very uncertain again.

Trump has said he's going to pull the US out of the Paris climate agreement. Will he, and will the planet ever forgive the US if he does?

Trump campaigned on pulling the US out of the agreement, so if we take him at his word, that’s where we’re headed. Now, it wouldn't be easy or quick to do that, but the US could do a lot a lot of harm to the deal even if it takes several years to pull out, or doesn’t officially pull out but just decided not to keep the commitments it made in Paris. Like funding, for instance — among other things, the US pledged a lot of money to help poorer countries around the world deal with climate change. If we stop doing that, that by itself is a big monkey wrench in the works.

As for whether the planet will forgive us — well, the planet may already not forgive us, Trump or no Trump. Industrial pollution already in the atmosphere has likely locked in a lot more warming, and all the impacts that will bring. The climate system is very unforgiving, and the basic physics are really pretty simple. Research looking far back into the Earth’s history shows that the amount of heat trapped by the atmosphere closely tracks changing levels of greenhouse gases. We’ve already knocked the climate system out of the stability that's supported human civilization for 10,000 years, and no one knows how to get back to that in any meaningful timeframe.

That's not to say, though, that what happens the next four or eight years under Trump isn’t important. It’s very important, because many of the best scientists out there say we’ve got a very small window — maybe just a few years — to squeeze through to make sure we don't cross a threshold toward inevitable, catastrophic climate change. If the Trump administration puts the brakes on efforts to fight climate change, that window’s likely going to get even smaller.

And what about adaptation to climate change? If Trump and members of his administration think it’s a hoax, would they back away from plans to protect shorelines, or to think about ways of, for instance, protecting the Mississippi Delta from a category 5 hurricane?

Trump has nominated climate change deniers to lead some of the most important climate-policy agencies, including the EPA and the Department of Energy. And to be sure, if they’re approved by the Senate, they can undo a lot of what's now in place to help protect coastlines and other regions from some of the effects of rising seas and other impacts of rising global temperatures.

Related: Living with Rising Seas

On the other hand, a lot of what happens in individual states and localities around the country comes down to policies and actions in those places. And that can be a very different picture, because a lot of states — especially a lot of coastal states — understand that climate change is real and that they’d better do something about it, whether Washington is in the game or not.

A lot of climate scientists say if we really want to reverse this climate change thing we have to keep fossil fuels in the ground. So what are Trump's plans for oil and coal?

We heard a lot of very strong pro-coal and pro-oil rhetoric from Trump in the campaign. He’s promised to restore coal jobs and unleash the drilling rigs. And here too, he hasn't given any indication of backing off these promises. But the reality is that it’s going to be very hard to do what he’s promised, especially when it comes to coal. We’ve heard a lot on our own airwaves recently about some of the bigger economic and technological trends behind the decline of coal in particular, much more so than even policies coming out of the White House and the EPA under President Obama.

Certainly, Trump and his allies in Congress can try to roll back the clock on fossil fuels. They can get rid of things like subsidies and tax breaks for renewable energy and electric cars, they can make more land available for oil drilling and other resource development. But it will be very hard to return to the energy picture of 40, 20 or even 10 years ago, regardless of what Trump does. Fracking, for all its faults, has flooded the market with cheap and relatively clean natural gas. Renewable energy technology is advancing incredibly quickly. The US and global energy economies are shifting along with these changes, and the demand is moving strongly away from the fuels of the past to the technologies of the future. This is not to say there won’t be more coal dug out of the ground, more oil and gas pumped up. But in the big picture, the country and the world are moving in another direction, and even the president of the United States can’t stop that.

Speaking of the big picture, when you think about the future of the environment under President Trump, what is the big story that occurs to you about the United States’ interconnectedness with the rest of the world?

A lot of it is about that very idea of interconnectedness, which Trump essentially rejects. His philosophy, to the degree that you can define it, is basically that the US should act alone and always in its own interests, that we should be helping ourselves instead of making big commitments to work with and help others. To many people’s eyes that ignores the reality of problems like climate change. The climate crisis is a global problem, one that’s been caused by all of us, affects all of us, and can only be solved by all of us. Certainly some of us bear more responsibility than others — the United States bears the most responsibility for climate change so far as the largest carbon polluter to date, so you could argue that we have the most responsibility to do something. But we’re all in it now, it's a global problem that requires a global solution.

Also, as we cut ourselves off, other countries are going to respond, and maybe they're going to do things like slap tariffs on us. Donald Trump talks a lot about putting tariffs on imports from other countries for unfair trade practices. Well, if other countries put a price on climate-warming carbon pollution to force down emissions, and we don’t, those other countries might consider our lack of action an environmental subsidy, an unfair trade practice that they should fight back against with tariffs of their own.

Finally, after all that effort and energy the US spent to get China on board with the climate treaty, could we be looking at a scenario where China is actually taking the lead in fighting climate change?

I think we might already be seeing that. After years of not taking it so seriously, and of saying, basically, “this was your problem, you started it, we have to look out for ourselves and improve our economy and our standard living,” they’ve really gotten serious about climate change. They worked closely together with President Obama the last few years but they don't need us to keep going. And they’ve got other economic and public health interests that are very strongly behind the push they’re making a move away from coal, away from dirty development, to clean development.

Editor's Note: The broadcast version of this story incorrectly stated that four of the last five years ended as the hottest on record. Assuming 2016 does end up ranking #1 as predicted, it will rank ahead of 2015 and 2014 on NOAA's list. The next hottest year was 2010, followed by 2013. So while 2013 is among the five hottest years on record, it ended the year as only the second-hottest on record.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!