Brazil is accused of stripping away LGBT rights

Members of Brazil’s lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community posing for a portrait inside a free residential shelter called CASA 1 or “House 1” in downtown São Paulo on May 16, 2017.

A recent court ruling has opened a fierce debate in Brazil about the use of controversial practices to make people become heterosexual.

Last month, a Brazilian federal judge decided psychologists could perform “conversion therapy,” a widely discredited practice meant to change a person's sexual orientation.

The so-called therapy has also caused controversy in the US, where a growing number of states are outlawing the practice. But while the US has never taken a federal stance on it, Brazil’s Federal Council of Psychology banned the practice back in 1999.

That didn’t stop a group of 23 evangelical psychologists from carrying out the “treatment.” Leading member Rozangela Alves Justino describes herself as a “missionary” who is “directed by God to help people who are homosexual.” She lost her license for continuing to perform the therapy and then brought her case to court.

Judge Waldemar Cláudio de Carvalho’s ruling means that Justino and her colleagues can resume their work.

“We consider it a huge setback to have to reaffirm, in the 21st century, that homosexuality is not a disease, disorder or perversion,” Brazil’s psychology council said in a statement following the judge’s decision.

Just want ‘to help people who come with a desire to change’

Justino has defended the practice on the basis that her patients are uncomfortable with their sexuality. “I think it’s cruel to be a person who wants to help and to be gagged, unable to help people who come with a desire to change,” she said in a 2009 interview. Neither Carvalho nor Justino have issued statements since the Sept. 15 ruling.

“All reputable psychiatric and psychological associations have condemned this practice as utterly unethical,” Graeme Reid, head of Human Rights Watch’s LGBT division, told PRI. “People who are offering these services are acting contrary to world medical opinion. It reveals the prejudice that gives drive to this kind of so-called treatment.”

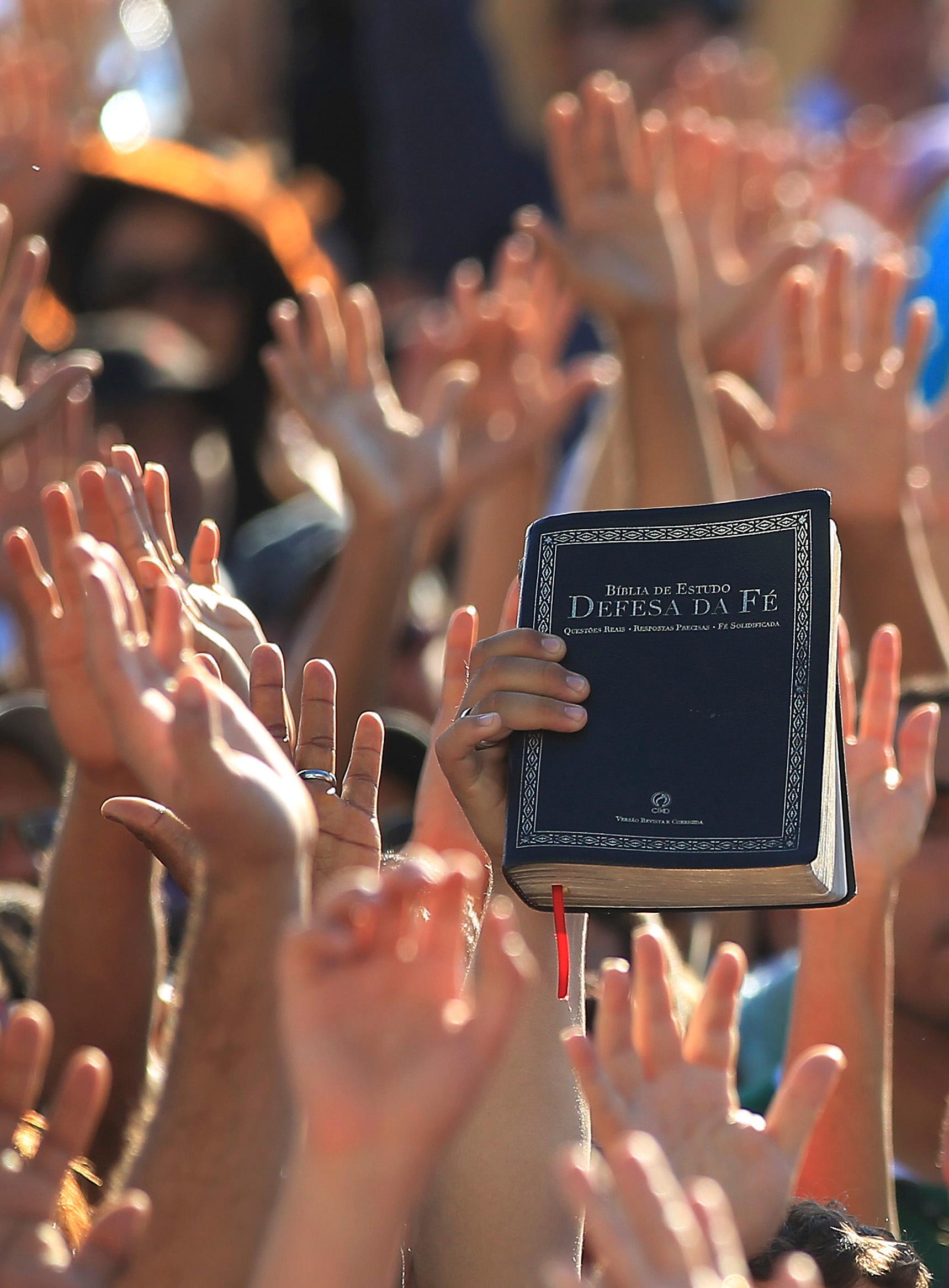

Brazil has long had a gay-friendly reputation. It’s one of the world’s largest nations to recognize same-sex marriage. But that’s just part of the story. LGBT individuals here also suffer discrimination, violent attacks or other serious problems leading to suicide. Today, researchers say the growing power of evangelical Christian groups is fueling prejudice and intolerance in the country’s political, professional and cultural circles. Increasingly, those outside of the heteronormative or religious mainstream are becoming targets for intolerance.

Although the ruling and the museum closure were both bloodless, they represent a subtle erasure of LGBTQ rights to public space and participation. Jurema Werneck, director of Amnesty International in Brazil, said the country should do more to uphold its citizens’ constitutional rights. “These debates make explicit the vulnerable situation of the LGBT population, particularly the trans population,” she said.

Angelo Brandelli Costa, a researcher at Porto Alegre’s Catholic University who specializes in LGBT psychology and homophobia, says Brazil is lagging. Where other countries have put in place social inclusion programs, he says, Brazil is still struggling to uphold basic human rights — such as safety on the street — for LGBT people.

“Public space for debate is taken by conservatives, who use the space for discussing repressive measures when we should be looking at protective measures,” Costa said in a phone interview.

Brazil’s second-largest television network, owned by a conservative evangelical bishop, has helped elect 24 current congressmen in Brasilia. And at local levels, powerful Pentecostal and Baptist churches are gaining influence in city and state governments across the country, posing a challenge to secular moderates but also to other members of the clergy in what’s traditionally been considered the world’s largest Catholic nation.

Costa added, “The biggest danger is that we are losing time debating what has already been consolidated in scientific literature when we should be debating protective measures.”

Deadly year for LGBTs

International health experts and rights advocates have broadly denounced conversion therapy, also sometimes called “reparative therapy.” The World Health Organization said it promises “‘cures’ for an illness that does not exist.” And the American Psychiatric Association has cautioned about the risks for patients who receive it, including depression and self-destruction.

United Nations research points out that suicide rates are higher among those who suffer discrimination — a phenomenon that Costa further backs up with research. “In comparison to heterosexuals, LGBT youth from low-income backgrounds are hugely vulnerable to suicide,” he said. “It’s clear that this prejudice and discrimination has an effect on victims, with the rise in suicides and depression, and that the larger visibility of contrary groups causes this effect for the victims.”

This year may end up being the deadliest year researchers have ever recorded for LGBTs in Brazil.

Suicides are taken into account in the deaths recorded by Grupo Gay da Bahia, a nongovernmental watchdog, although they are far outnumbered by gruesome murders. The NGO, which is the only Brazil-based organization monitoring crimes against LGBT in the country, recorded 343 violent LGBT deaths in 2016 — approximately one every 25 hours. So far in 2017, Grupo Gay da Bahia has already recorded more than 300 related deaths.

The group’s founder and coordinator Luiz Mott called the increase “very worrying.”

Mott also pointed to the refusal of certain local leaders, including Rio de Janeiro’s evangelical Mayor Marcelo Crivella, to support gay pride parades. “All of this reflects an increase in intolerance, which unfortunately could further increase the number of lethal crimes,” he said.

Related: Rio just elected a very conservative mayor. Activists are worried about LGBT rights.

Crivella, who was the bishop of a controversial megachurch, wrote in the past that homosexuality was a “terrible evil,” but later apologized for that characterization during the campaign for Rio mayor.

He has funded an office of sexual diversity that’s coordinating smaller gay pride parades in neighborhoods across Rio now that city funding has been withdrawn for the flagship parade in Copacabana.

However, on Oct. 1, Crivella’s office posted a video on social media showing the mayor promising a group that the queer art show would make its way to Rio “only if it’s at the bottom of the sea.” The Rio Art Museum, known as the MAR, which receives funding from the city government, has since decided not to host the exhibition.

Researcher Costa says that rollbacks to LGBT rights are a casualty of Brazilian evangelicals’ aim to raise their profile and sway on national politics.

The group’s congressional bloc also played a key role in supporting last year’s impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff for budgetary crimes.

“With the end of a left government in power, these progressive issues end up stuck as a part of a leftist agenda,” Costa said. “With the current political polarization, LGBT issues end up lost as well.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?