Meet the winner of the ‘Nobel for human rights’ that Egypt doesn’t want you to know about

Mohamed Zaree giving a talk with the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies in Egypt.

At an awards ceremony on Tuesday in Geneva, dignitaries from the United Nations and the Swiss government, along with diplomats and members of the international human rights community, came together to recognize the work of human rights defenders worldwide at risk of persecution.

But one seat was notably empty: that of Mohamed Zaree, this year's winner.

He can’t leave Egypt because he was slapped with a travel ban by the Egyptian government last year.

Egyptian activist Zaree, 37, was awarded the prestigious Martin Ennals Award — often called “the Nobel Prize for human rights” for its global scope and recognition. It’s named after Amnesty International’s former secretary-general.

He was selected from three finalists by a jury comprising representatives from 10 leading international rights organizations, including Amnesty and Human Rights Watch.

In an interview with PRI before the award announcement, Zaree said he was very grateful to be nominated, if anything for the extra security it could potentially give him by raising his profile abroad.

“Being recognized in a prestigious award,” Zaree said, “this is a kind of protection.”

It’s little surprise he’s concerned about his safety at a time activists in Egypt are facing harassment, intimidation and increasing legal and extrajudicial threats from the country’s ruling regime.

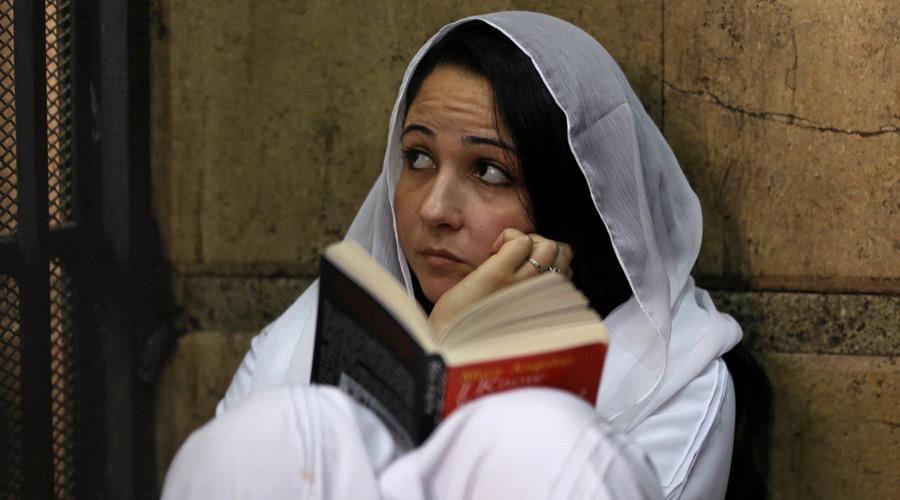

Zaree is a key member of the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies, a nonprofit group that’s instrumental in protecting other humanitarians, including in the world headline-grabbing case of Egyptian American aid worker Aya Hijazi.

The institute was created in 1993 to promote human rights and democracy in the region. Zaree joined the group soon after the 2011 revolution that toppled long-time leader Hosni Mubarak.

Now, critics say Egypt’s current President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi is intensifying a campaign to wipe out the country’s independent human rights movement, and Zaree and the center where he works are among many being targeted.

Zaree is one of several activists Egyptian authorities banned from travel in relation to a case dating back to 2011 against nongovernmental organizations, including the Cairo Institute, which the state accuses of acquiring illegal foreign funding to harm Egypt’s national interest. The “foreign funding case,” which Amnesty International says is “politically motivated,” was revived last year.

This past May, a year after Zaree was barred from travel, the investigative judge in the case pressed charges against him. He faces possible life imprisonment if found guilty of receiving funds from abroad and spending them unlawfully to destabilize Egypt.

Zaree completely rejects the charges against him and the others named in the trial. “The case is actually punishing us for our work and for exposing the human rights violations in Egypt,” he said. The government has no tolerance for those who expose its repression, he added.

The foundation that presents the Martin Ennals Award said that Zaree is one the defenders picked out by the regime for his “leadership role” in bringing to light these violations and “his tireless advocacy for human rights,” which he continues to do “despite the relentless and escalating risk and persecution he faces on a daily basis.”

Faced with ever increasing threats to its work, the Cairo Institute moved most of its operations to Tunisia in 2014 and its founder and director, Bahey Eldin Hassan, also went into exile abroad.

Zaree is one of the few members of staff still left working inside Egypt. They no longer work from an office in Cairo because it’s too dangerous for staff. Their work has been further hamstrung after the organization had its assets frozen in the foreign funding case.

In his place, Zaree’s wife and two daughters as well as his boss attended Tuesday's awards ceremony in Geneva.

Early defenders of an Egyptian American prisoner

Despite the hurdles, Zaree and the team in Egypt continue. They were for instance, among the first to come to the aid of American Egyptian humanitarian worker Hijazi before her case became high profile.

Hijazi was jailed for three years in Cairo on charges that were widely condemned as politically motivated. She was finally acquitted earlier this year following intervention from the Trump administration.

Related: American charity worker in Egypt is acquitted after three years in jail

But victories like this are short-lived and are “swallowed by the unprecedented crackdown,” Zaree said.

It “was rewarding to see Aya Hijazi and her colleagues free” he said. But on the same day as her acquittal he was accompanying a colleague from another human rights organization to an investigation session for the “foreign funding case.”

And then just a month after Hijazi’s verdict, Sisi ratified a highly restrictive new law that Amnesty International warned “threatens to annihilate NGOs in the country.”

“If there is a victory, a small victory here and there, you’ll always find that there is another disaster that will destroy the happiness of your victory,” Zaree said.

Few resources and little capacity make it especially hard to keep up with the pace of repression, he added.

Just the day before this interview late last month, a prominent rights lawyer and potential presidential candidate, Khaled Ali, was convicted of “violating public indecency” in what critics say is a politically motivated verdict to stop him from running against Sisi next year. (If an appeal’s court confirms his conviction he will be legally barred from the race.)

And just days earlier, Egypt’s LGBT community faced arrests and threat of anal examinations by the police, after a rainbow flag waved at a Cairo rock concert provoked a media outcry.

On top of that, 25 indigenous Nubian activists were arrested for a peaceful, singing protests; a lawyer representing families of people forcibly disappeared by the state was himself forcibly disappeared; over 400 were sentenced between five years to life imprisonment in a mass trial; and the Egyptian cabinet approved stripping citizenship from those convicted in crimes against the state — a move analysts say could be used against human rights defenders and other dissenters.

And that was just September.

The daily stream of human rights abuses like these, along with the constant threat of reprisals and possible imprisonment, have all taken a toll on Zaree’s health and are giving him anxiety attacks.

“If I keep thinking that I will go to jail … I will freak out and end up in a very small room in my house trying not to deal with anyone. So I am trying to be in denial but I can’t escape the panic attacks that I have sometimes,” he admitted.

He is trying to stay calm he said, for the sake of his family, especially his elderly mother who has high blood pressure. He and his wife are also trying to protect their two daughters who, at 4 and 7 years old, are too young to understand he is on trial.

But they found out about his travel ban because they noticed that the gifts of Legos he’d pick up for them on his trips abroad stopped and began asking their dad where the Legos are and why isn’t he traveling?

“So I told them that I won’t be able to travel again,” said Zaree, “that I didn’t do anything wrong and that they should be proud of what I’m doing.”

Salma Islam reported from Cairo.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?