The Catholic Church defies Philippine President Duterte

Remy Fernandez, 84 years old, holds her grandchildren that she is raising; there are seven in all, because her son, Constantino de Juan, a methampetamine user, was killed by masked men and the mother is in prison due to a drug arrest. The chair in which she sits has a hole in it after it passed through his body. Baby RJ was born in prison. Juan, upon seeing the masked assassins, instructed CJ, 5 years old and wearing the red tank top, to take care of his siblings because he knew he was about to be assassinated. This picture was taken in Payatas, Metro Manila, in the Philippines.

At the stroke of midnight on July 24, a group of about 150 gathered in a church not far from where Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte was scheduled to face Congress and deliver his second State of the Nation Address in Manila later that day.

Legislators, activists, church leaders and concerned citizens heard Mass, prayed and lit candles to start a 17-hour vigil in protest of the Duterte administration’s brutal drug war that has left thousands of mostly poor, young men dead.

“We held a similar Mass last year before the president’s first SONA. As soon as he [Duterte] had won the elections, the killings began,” said Father Joselito “Bong” Sarabia, a parish priest and counselor.

And they have not stopped.

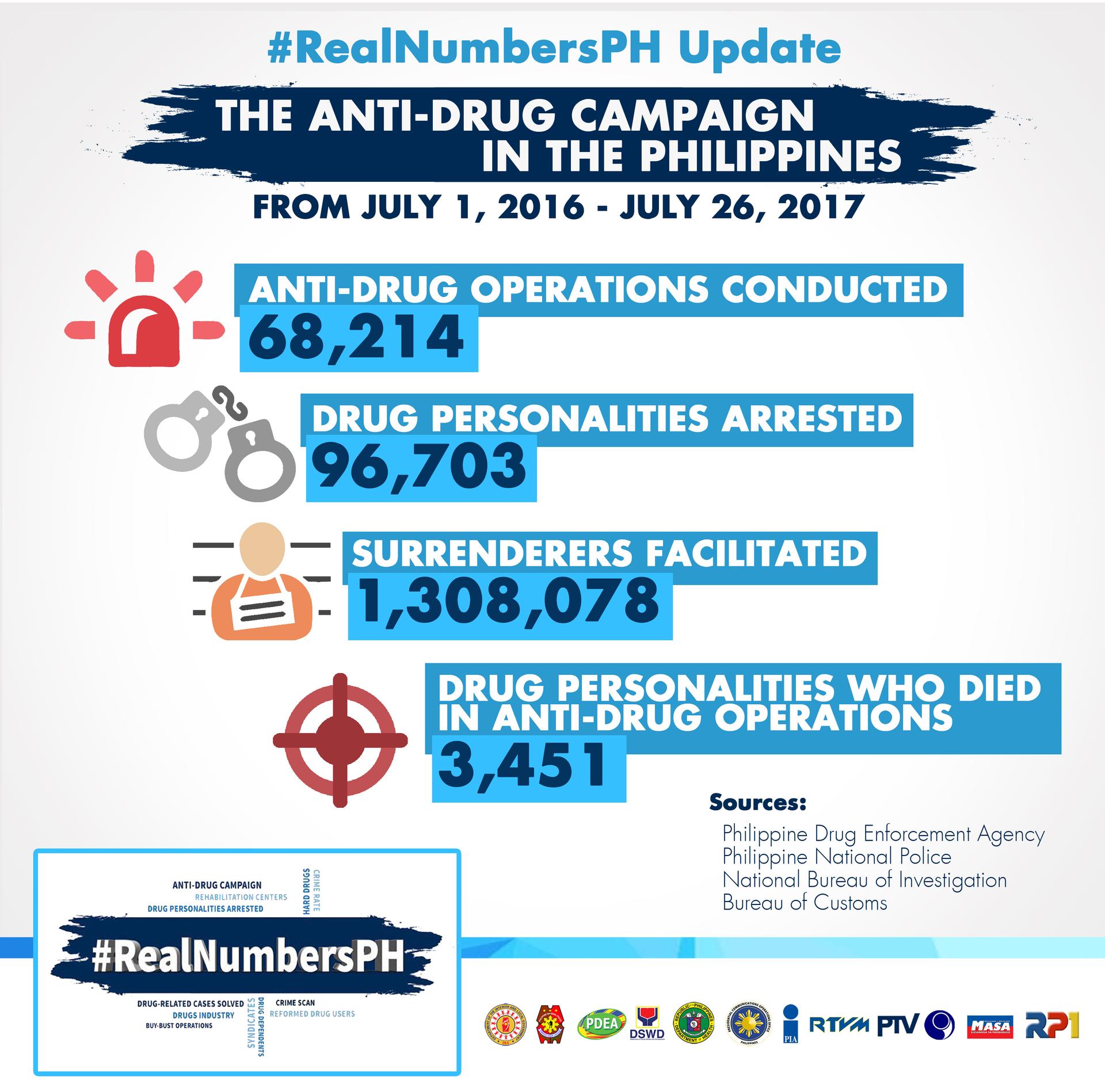

In the little more than a year since Duterte swept into the presidency and unleashed a vicious war on drugs, there have been more than 14,000 murders and homicides, according to government statistics. Of those, over 2,000 were determined as drug-related while more than 7,000 deaths were for unknown motives — what the government calls “deaths under investigation.” Additionally, more than 3,000 drug suspects were killed during anti-drug operations.

“There is a separate count for drug suspects killed in anti-drug operations. The clear difference is the criminal intent in murder and homicide cases while there is none of the part of law enforcement in the police anti-drug ops,” explained Dionardo Carlos spokesperson for the Philippine National Police.

Related: Neuroscientist Carl Hart says 'infant thinking' drives Philippines meth war

But some say that the actual numbers may be higher but are difficult to determine because of the government’s changing classifications of the cause of death.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

Today, in Manila, corpses stack up on street corners and under bridges, many of the victims allegedly killed by masked vigilantes on motorbikes, according to media and police reports. Some witnesses speak of more brazen attacks, where masked men barge into homes and shoot their identified targets point-blank. Other victims are reported to have been killed in shootouts with the police during drug raids.

“A victim’s mother told me that they know they are ‘unworthy’ people and that no one would stand up for them.” — Bishop Pablo David

The spate of killings and the deliberate manner in which they are being carried out has left gaping holes of grief and a fearful silence in the urban slum communities where they usually happen.

“A victim’s mother told me that they know they are ‘unworthy’ people and that no one would stand up for them,” said Bishop Pablo David about the muted outrage or uprising from communities. “It is as if we have accepted the narrative that people who use drugs deserve to die.”

David’s diocese includes some of the biggest slums in Manila, where most of the killings have taken place.

The dire situation has compelled the church to go beyond its usual liturgical services to attend to the needs of the families left behind, both spiritual and practical. The church has galvanized pastoral workers and trained them in grief counseling and raised funds to cover victims’ funerals and the survivors’ day-to-day living expenses. Some parishes have become sanctuaries — sheltering people who are hiding from police authorities, and others have assisted in relocating entire families to a distant province.

“We cannot let these killings continue. We will lose our conscience and our soul,” David said, during a recent phone interview.

The regular killings — an average of as many as six per night in Novaliches and Caloocan, the "hot target" neighborhoods — prompted David to engage police station commanders in his diocese in a dialogue. “I have asked them to investigate the deaths and urged them to solve at least one. Unfortunately, the killings come faster than the investigation.”

He is also alarmed by the pictures he has seen of victims whose hands show signs of being bound or tied, he says. The usual police narrative is that the suspect fought back, so he or she was shot and killed. But David is careful to maintain cordial relationships with law enforcement, explaining, “I’m not making accusations. I am [only] asking questions.”

“The loss of the family breadwinner is the biggest problem. Helping the families through livelihood is key to survival,” said Father Sarabia who works with Rise Up, a group of church officials and volunteers who support families of extrajudicial killing victims.

In addition to counseling and burial assistance, Rise Up offers interest-free loans to help families with their day-to-day survival.

Remy Fernandez's family is among those served by Rise Up. Remy lost her youngest son, Juan, 38, last December.

“I had asked him to hide when the killings started. He went home that day to celebrate the birthday of one of his daughters,” said Remy.

Masked men stormed into their home and shot Juan one morning while he was cooking spaghetti. The blue sofa where he died still bears the bullet hole. It was more than a month before Remy could bring herself to wash the blood off of it.

With Juan’s wife in prison, also for drug-related offenses, Remy, a widow, is left to support the seven children he left behind. Scavenging for recyclable trash and reusable metal is the only work Remy has ever known.

Remy’s neighborhood parish, led by Sarabia, has given her a couple of small, interest-free loans — $100 and $200, respectively — to help her manage her daily expenses. She already repaid the first loan that came through in January, and she’s getting by, but it’s tough to provide for five kids in school. At 84, she also has to care for two small children at home.

“The killings are unhealthy. It’s not a nice thing. People begin to doubt the police and the safety of our neighborhoods. But let’s give the situation ample time. It’s only been a year,” said Caparroso.

Sandy Caparroso spent his childhood near the Payatas dump where the Fernandez family lives. Now, as chief police inspector for the district he grew up in, he says the streets are safer than they were back then. He cites lower numbers of crimes such as robbery and car theft, but he acknowledges that there has been an increase in the number of homicides.

“The killings are unhealthy. It’s not a nice thing. People begin to doubt the police and the safety of our neighborhoods. But let’s give the situation ample time. It’s only been a year,” said Caparroso.

Political conscience

With Duterte’s 84-percent approval rating and trust rating of “excellent,” the church may be the only institution that can rival the president’s following and popularity.

Historically, the church has served as the political conscience of an estimated 90 million Filipino Catholics. In 1986, the former president and dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, was ousted through a peaceful street protest. Priests and nuns linked arms with private citizens and faced off with army tanks by praying the rosary and giving yellow flowers to soldiers. The rally was prompted by a callout from then-Cardinal Jaime Sin. In 2001, the church was also instrumental in calling people to an uprising and overthrowing President Joseph Estrada.

But times have changed. Despite 90 percent of the country’s estimated 100 million people being Catholic, the church's political influence and spiritual ascendancy have been tarnished by sex scandals and corruption allegations.

Sarabia says that divisions within the church also make it difficult to take a solid, unified stand. Some priests voted for and support the president, while others have chosen to remain silent out of fear of possible retaliation from vigilantes or vicious online attacks from Duterte supporters.

Related: The Filipino president has deployed a ‘social media army’ to push his agenda

Documentation

At the beginning of the drug war, the police provided regular statistics about the number of deaths in buy-bust operations and in vigilante killings. But after the murder of a South Korean businessman by law enforcement in police headquarters last February, the updates became more sporadic — and confusing.

The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism has questioned police statistics and criticized them for being “crowded with constantly changing concepts and terms” — with erratic numbers that are “inflated and then deflated and later inflated again.”

Human Rights Watch estimates that drug-related killings had already surpassed the 7,000 mark at the end of January, and says there are alarming indications that the current death toll is significantly higher.

“The government has frustrated efforts by media and other independent observers to maintain a transparent tally of the drug-war-related deaths by issuing contradictory data. That opaque statistical soup appears designed to confound parsing of the data,” said Phelim Kine, HRW’s deputy director for the Asia Division.

The church is also beginning to document cases themselves, which may be used as evidence later on. According to Sarabia, often, witnesses don’t want to tell the police what they saw, but they may be more inclined to open up to a church volunteer. This effort, too, prevents the victims from being reduced to statistics.

David is also urging mayors to set up local human rights councils in their cities to document and monitor cases. Meanwhile, the president has said he wants to abolish the national commission on human rights. Duterte’s statement was later qualified as a “joke.”

“I have resolved that no matter how long it takes, the fight against illegal drugs will continue. … The fight will be unremitting as it will be unrelenting. Despite international and local pressures, the fight will not stop. The alternatives are either jail or hell.” — President Rodrigo Duterte.

Other parishes like Sarabia’s have partnered with the Free Legal Assistance Group, the largest group of human rights lawyers in the country.

FLAG trains pastoral workers to gather and collate testimonies and copies of police and autopsy reports.

“Many of the victims are reluctant to seek justice. The situation may change at some point, and they may want to pursue a case,” said Jose Manuel Diokno, FLAG founder.

“I don’t think the situation that we have now will last forever. Those who hold power now will not hold power forever. When that time comes, they must be held accountable,” Diokno concluded.

At the president’s second State of the Nation Address in July, Duterte reinforced the campaign promise that won him the presidency: “I have resolved that no matter how long it takes, the fight against illegal drugs will continue. … The fight will be unremitting as it will be unrelenting. Despite international and local pressures, the fight will not stop. The alternatives are either jail or hell.”

His proclamation was met with resounding applause from Congress.

Ana P. Santos reported in Manila. Reporting for this project was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.