This Canadian oil pipeline could cause the next great controversy

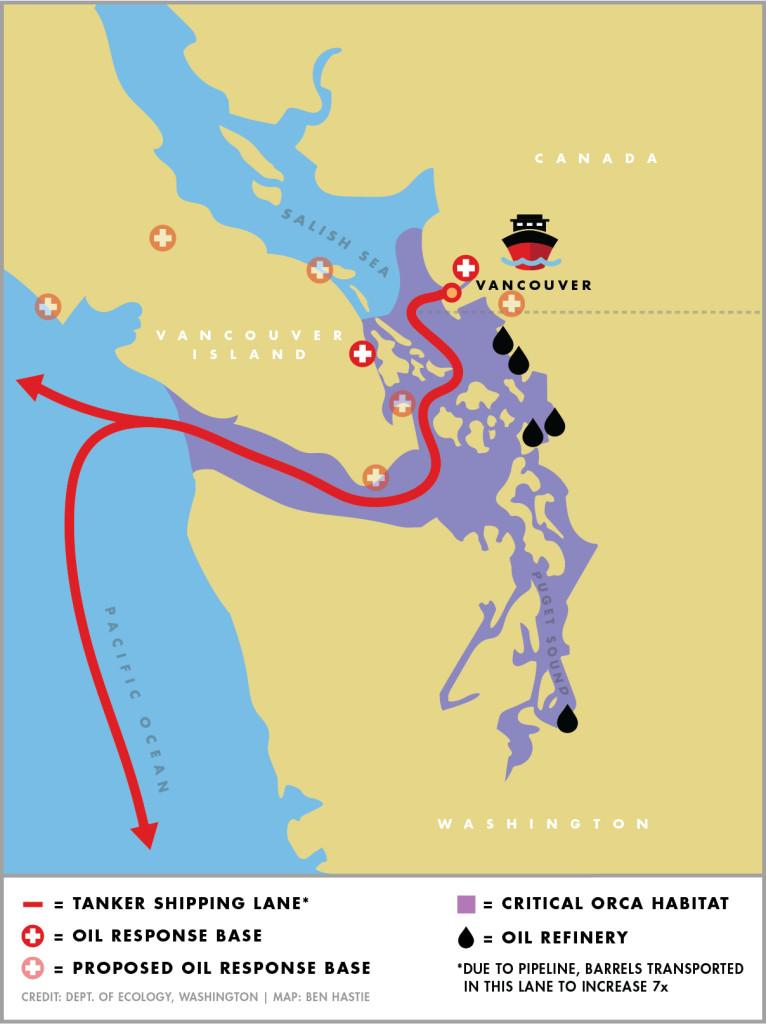

Oil flows through pipes to the Westridge Marine near Vancouver, BC. A second, much larger pipeline here is part of Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's plan to increase exports of oil from Alberta's tar sands region. Opponents say that would increase carbon pollution, trample on native lands, and threaten a vast marine ecosystem shared by Canada and the US.

The Westridge Marine Terminal overlooks a finger of water that separates Vancouver, BC, from the deep green hills of the nearby provincial parks. It’s where oil tankers come to fill up, at the terminus of the TransMountain Pipeline, which winds down through the trees and straight out onto a dock.

The pipeline’s been carrying oil here from the tar sands of Alberta for decades, but it’s a pretty sleepy operation by industry standards.

“It’s the Honda Civic of marine loading facilities,” says Mike Davies, the director of marine affairs for pipeline owner Kinder Morgan. “This is a very small facility.”

Only about 60 tankers a year call at Westridge. But that could change soon, because Kinder Morgan wants to build a second, much bigger pipeline from Alberta. When it’s done, tanker traffic would shoot up to about 400 ships a year, bound for California and Asia.

Davies says that would relieve a big oil bottleneck.

“Canada has the third-largest reserves of petroleum in the world, and we currently only have the ability to trade with one other country, which is the United States,” Davies says. "It's just good for Canada to be able to reach other markets.”

Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau thinks so too. Since coming into office in 2015, Trudeau has pledged big cuts in carbon pollution under the Paris Agreement to fight climate change. But he’s also a big booster of Canada’s oil industry. And he says building new pipelines would create jobs without busting Canada’s carbon budget.

Related: Climate warrior? Champion of 'Big Oil'? Canada's leader wants to be both.

But many people take issue with Trudeau’s math and his philosophy, partly because tar sands oil is some of the most carbon-intensive in the world.

“If you are advocating and planning to build two major pipelines from the dirtiest oil in the world with nearly two million barrels of oil flying out of that place per day, you are not within the Paris climate agreements,” says Paul Che oke ten Wagner. The new pipeline would pass through his British Columbia homeland — the Saanich Nation.

Wagner lives in Seattle now, and says he didn’t actually pay much attention to the pipeline plan back in BC until some friends invited him to go with them to Standing Rock, North Dakota, last year. That’s where other Native Americans were protesting another oil pipeline.

He says he came back a changed man.

“Coming home from Standing Rock was one of the biggest challenges I’ve ever had in my life,” Wagner says. He was moved by the thousands of other protesters, “all doing it for the protection of water, protection of their traditions, their children and for the future generations.”

After he got home, Wagner helped led a four-day march along the waterways south of Vancouver that all those new oil tankers would ply. The protesters were marching in support of legal challenges in Canada against the new pipeline. And they were joined by about a dozen people from the US side of the border, motivated by concern for indigenous rights, climate change and their own backyard, which they share with Canada.

The proximity is clear from Deborah Giles’s office on Washington state’s San Juan Island. From her window, she points across the narrow Haro Strait to the city of Victoria, BC — just a few miles away.

“We can see the tallest buildings sticking up over the ridgeline there,” Giles says.

“Noise is one thing,” Giles says. Ship noise can interfere with orcas’ ability to find food and communicate.

But she also has a bigger concern.

“The potential for oil spill is astronomically more scary, because … there’s this crazy, random border,” Giles says. “If oil gets spilled in Canada, it’s not going to end at that imaginary border. It’s going to decimate this entire ecosystem.”

The marine ecosystem here stretches from Vancouver Island in Canada, down to Seattle and Puget Sound in the US, and out to the Pacific. It’s home to millions of people and invaluable marine resources.

But Davies of Kinder Morgan, says the risks of an spill are exaggerated.

“We've never had a release from a tanker loading in the 60-year-plus history of the operations here,” Davies says. Still, Davies says Kinder Morgan is helping beef up spill response systems on the Canadian side of the border.

Of course, with a more than six-fold increase in traffic, the risk of a spill is considerably greater than it has been in the past.

Despite the possible impacts to their local communities and environment, people like Deborah Giles on the US side of the border have no sway over whether the new pipeline gets built and the new tankers start streaming through. But BC’s First Nations could influence the outcome, because the pipeline route would pass through some of their traditional territories, including the home of Wagner’s Saanich Nation.

And Wagner says they will fight it.

“They cannot trespass upon their land without the acknowledgement of those first peoples, and their saying, ‘Yes, you can do that,’” Wagner says. “And so over 100 tribes have signed onto an alliance, saying, ‘No pipelines will cross our borders.’”

First Nation legal challenges are working their way through Canada’s courts. But, even if they fail, Wagner says he’s not giving up. He’s ready to launch a Standing Rock-style protest in Canada.