Photographer Nima Taradji saw a live match of lucha libre for the first time during the May 29, 2016 Mole de Mayo street festival in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago. He was impressed by its pageantry, acting and athleticism. His photography documents a spectacle that arrived to Mexico from the US in the 1930s, developed its own Mexican forms and traditions, and now returns to the US, where it is still evolving.

Every year, at the end of May, crowds gather in the Chicago neighborhood of Pilsen for the annual Mole de Mayo street celebrations and watch the feats of local luchadores. In an improvised ring, several men and a couple of women engage in fights similar to US professional wrestling, but with a Mexican, acrobatic twist.

Many of them — along with the children in the audience — wear the masks that have come to represent the sport in Mexico.

The Mole de Mayo fights were surrounded by street vendors, mariachis and other activities reminiscent of Mexico. Thousands of people attended the three-day festival. On other days of the year, the luchadores train and perform in Galli Lucha Libre in Villa Park, the only permanent lucha libre gym in the Chicago area. Hundreds of people attend these weekly events.

Luis Marentes, a professor of Latin American and US Latin@ literature and culture and member of the Global Nation Exchange on Facebook, discussed the event with his brother-in-law, photographer Nima Taradji, about how he sees this spectacle that crosses borders.

Taradji been observing this tradition since 2016. What emerges from his lens is a view of a world in constant contact and transition, as he chronicles a spectacle that arrived to Mexico from the US in the early 1930s, developed its own forms and traditions, became a symbol of a Mexican identity, and now returns to the US, where it is still evolving.

Luis Marentes: How did you discover lucha libre in Chicago? And as a photographer, why did you want to focus on it?

Nima Taradji: I saw them at last year’s Mole the Mayo and instantly became interested in the culture of lucha. The pageantry, the over the top acting, the real athleticism required to perform well — all was intriguing and I wanted to know more about it.

Often times, the projects I take on are really for me to learn about the subject matter I am photographing, and photography is a means by which I get access to places where I might not be able to otherwise go. I wanted to know more about lucha and the machinery behind it.

As a documentary photographer, I get access to the private home of a transgender person, or backstage during a burlesque show. In the instance of lucha libre, I get access to private training sessions where the fighters learn about falling, hitting and various techniques used during matches — those are private areas where the general public is not allowed. Even during the public event, I get access to the backstage where strategies are discussed.

You seem to be very interested in the narrative of good versus evil. How do you see this playing out in the spectacle of lucha libre?

The entire premise of lucha libre is based on the fight between the good and evil — the técnicos and the rudos. So the good and evil, or the “bad” as they sometimes call themselves, play an integral part of the entire presentation. From the story lines that surround each character, to the audience participation and expectation of the outcome, the entirety of the conflict is about the struggle of the good over bad and the bad over good.

The notion of the struggle between good and evil is a recurrent theme in many different cultures, be it in religious traditions or political principles. A parallel can easily be drawn in which the técnicos represent the God-fearing farmers and workers engaged in honest struggle to survive while facing daily assault by those who wield power over them. Rudos can be interpreted to represent the oppressors: factory owners, landowners, managers, politicians and law enforcement officers. Lucha libre embodies the proletarian struggle for justice — a justice that, in real life, is often non-existent but in the fantastical world of the ring happens on a fairly regular basis. Each match, each lucha, depicts the struggle between this good and evil — and, as it should be, the good often (but not always) beats evil, often quite literally.

How do you see the interaction between the Mexican and North American wrestling traditions displayed in the matches?

They are two different and distinct traditions. Although there are American luchadores who participate in the lucha libre, while they are doing so, they respect the rules and traditions imposed in the lucha fights.

In the Mexican tradition, the masked luchadores’ identities are well-kept secrets. When they appear in public or whenever they are being photographed, they wear their masks. When I was given access to the backstage, I was warned that I was not to take photos that could reveal the identity of the masked luchadores. When I photographed the training sessions, they all made sure that they had their masks on, even though during normal training sessions, they don’t usually wear their masks.

By contrast, the identity of the American wrestlers who participate in lucha is already known and therefore wearing a mask is an option.

Also, in contrast to the American style of wrestling, lucha libre is known for its spectacular aerial moves, where the fighters use the ropes around the rings to propel them onto the air in spectacular flying acrobatics.

You were born in Iran and lived in France for a while before moving to the US. Can you tell about how this journey has informed your photography?

At the outset, these facts have made me cognizant of the existence of different cultures that are all no more or less important than each other — they are simply different outlooks on societal interactions. There is no question that having lived in more open societies and having had access to a broad range of opportunities in terms of schooling, access to movies and books of different and varied nature, have had an effect on my outlook on life.

For example, I remember seeing an exhibition of photography by William Klein, an American-born photographer living in Paris, when I lived in France in the mid 1970s. I was 16.Those photos changed my vision about photography all together. It showed a new approach referred to as “street photography” and I became enthralled with it. It included the notion of the decisive moment, something generally known as a moment in time when all the objects in a photograph come together spontaneously in a certain specific and unique way to form the essence of the event photographed. Before that time, I had a more general approach to photography. After having seen Klein’s photography, I became more focused on what I wanted to see in my photographs. That is, I focused more on people, their interactions with each other in the public arena and their relationship with the spaces they occupied.

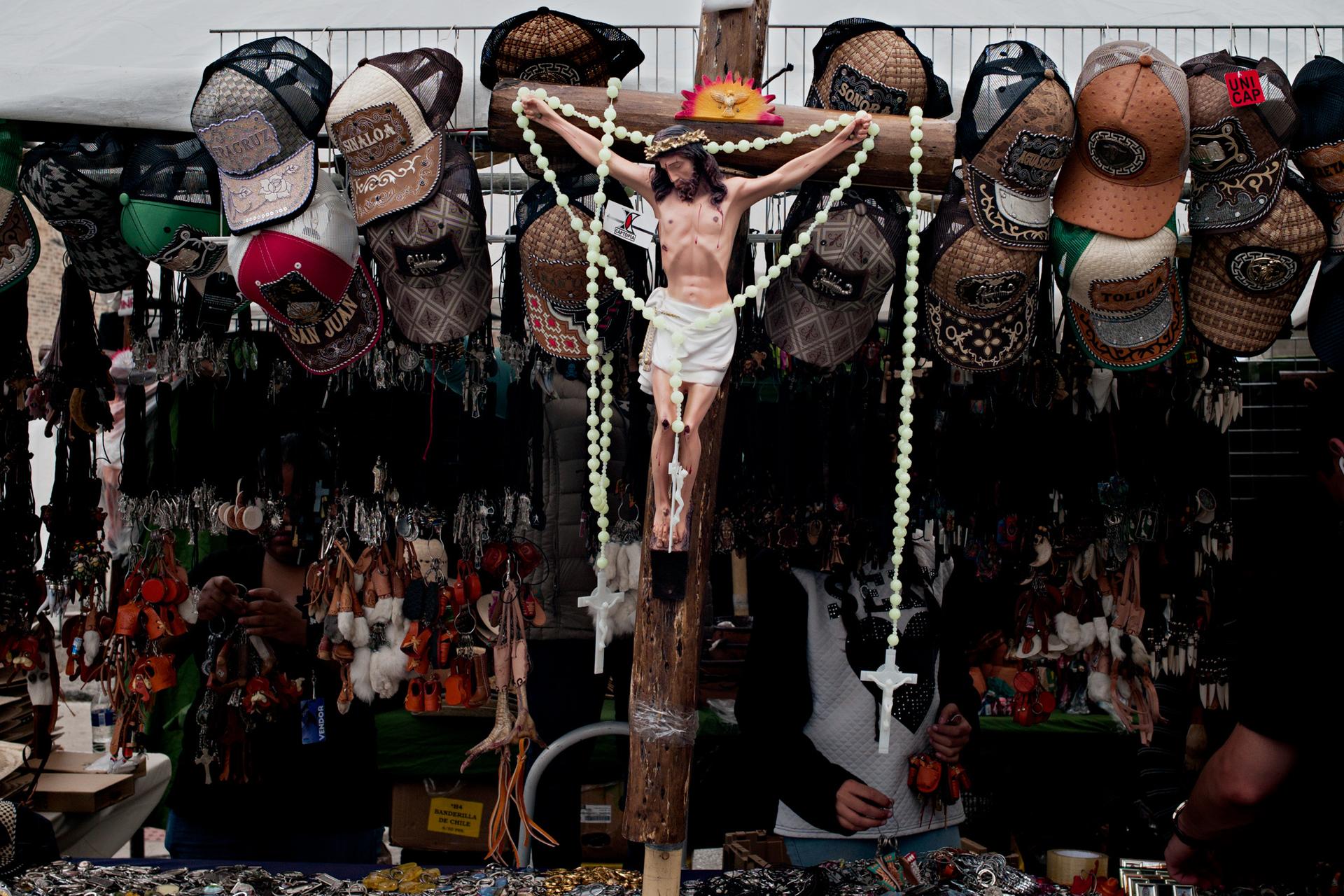

When contemplating the places I have lived — aside from Iran — in southern France, Texas, Los Angeles and now in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago, the Latino culture has been prevalent in all these areas. In all these places, I was exposed to the Catholic pageantry, the spectacle of religious traditions as performed in churches, the religious characters and the theatrical display of religious suffering (for example in re-enactment of religious event such as the Via Crucis). I see a parallel between the religious theatre — I use the word theatre not in a pejorative way but simply to refer to enactments of religious traditions — and the theatre of lucha. When looking at religious events and lucha one can hardly not notice the parallels: the struggle between good and evil, the pageantry of various characters and the suffering — seemingly real — of those characters engaged in their struggle.

I attempt to capture these public events in the spirit of “street photography,” as I saw with William Klein.

Join us for a conversation about lucha libre and other traditions that are transformed as they cross borders. Nima Taradji is discussing his work and life with us in the Global Nation Exchange on Facebook. He’s the first to join us in a series of conversations about the moments when different immigrant groups interact in the US. How are we different and how are we similar — and how do we create new American traditions?

Luis Marentes is a professor of Latin American and US Latin@ Literature and Culture at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Nima Taradji is his brother-in-law. See more of Taradji’s photography of lucha libre in Chicago on his website.