New hope for a Sudanese asylum-seeker stuck in an Australian offshore detention camp

Sudanese asylum-seeker Abdul Aziz Muhammed, who has been stuck in an Australian-funded immigration detention camp on a remote island in Papua New Guinea for nearly four years, is pictured here. His only hope is that the Obama-era agreement to resettle refugees like him to the United States is honored.

UPDATE: This story was originally published on April 7. On April 22, the Trump Administration said it would honor an Obama-era agreement with Australia, under which the United States would resettle up to 1,250 asylum seekers stuck in offshore processing camps on two South Pacific islands: Manus in Papua New Guinea and the tiny island nation of Nauru. Back in January, President Donald Trump described the deal as "dumb".

In Sydney, Vice President Mike Pence said the deal would be subject to vetting and that honoring it "doesn't mean we admire the agreement." Part of the agreement is that in return for the US taking the refugees from Manus and Nauru, Australia will resettle some refugees from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras who are in refugee camps in Costa Rica.

This means that Abdul Aziz Muhamat, who has been in the detention camp on Manus Island for almost four years (and the subject of our story below), has a good chance of being resettled in the United States. We will continue to monitor the story.

Remember that "dumb deal" President Donald Trump tweeted about back in January, after his less-than-cordial phone call with Australia's prime minister?

It had to do with an Obama-era pledge to accept migrants into the US that Australia rejected. Trump put it this way:

Well, some of those "illegal immigrants" have been stuck in Australian offshore detention camps for almost four years. One of them is Aziz, a 25-year-old asylum-seeker from Sudan.

"We have been locked away in a place where it's an isolated island and far away from the [others]. When you cry or when you scream, no one can hear you."

Aziz had the bad luck of entering Australian waters aboard a smuggler's boat from Indonesia in October 2013, just a few months after a new law had taken effect. The law said that asylum-seekers arriving in Australia by boat would no longer be allowed into the country, ever — not even for processing. And so after his boat was intercepted, Aziz was flown to an Australian-funded immigration detention center on Manus Island, which is part of Papua New Guinea.

Fast-forward some 864 days, to March 2016. Aziz gets a WhatsApp audio message from Australian journalist Michael Green. Green was investigating conditions in Australia's detention camp on Manus Island, and someone gave him Aziz's phone number.

His first audio message to Aziz: "Hi, this is Michael here. I just thought that I would leave a voice message so that you could hear my voice. Bye."

Aziz responded. "Michael, yeah bro. Uh, how you doing? Um, good to hear from you. So, how's your day and how things are going with you down there?"

Green was entranced. "From the first night that I sent him messages, really from the first one, Aziz was just so warm and generous with his answers. And I had been a bit apprehensive because, you know, who am I? I'm just some guy contacting him."

Some 3,600 audio messages later, Green and Aziz are still audio pen pals. The Australian journalist has created a podcast, The Messenger, about Aziz and what life is like for those in indefinite detention in Australia's deeply disputed offshore camps.

The Australian-funded camp where Aziz resides is called the Manus Regional Processing Centre, but there hasn't been much processing of the detainees' asylum applications. Many of the roughly 800 men at Manus have been languishing there for several years.

For Aziz, his audio messaging relationship with Green has been a godsend. In one early message, Aziz says: "I was just looking for something … to pass … my time. And I was looking for something that [can] help me to reinvigorate my memory. To be honest, I forgot heaps because our brain is not really functioning anymore because we have been in this place for a long time and whatever we had got we had lost it."

Aziz had a tough life even before he ended up in indefinite detention on a remote Pacific island. He's from the Darfur region of Sudan. His family fled their village when he was 16 because of the conflict there. For the next three years he lived in a refugee camp — his family is still there — until his father persuaded him to leave. Sudanese rebel militias were raiding refugee camps and looking for fighting-age boys. Aziz first made his way to Sudan's capital, Khartoum, to live with an uncle. But it was too dangerous there so he proceeded to Indonesia. That didn't work out either. His final try: the smuggler's boat to Australia which landed him on Manus Island.

Conditions at the Manus camp are grim. Early on, the detainees lived in tents and there was no air-conditioning on the blazing hot tropical island. For a long time they couldn't leave the camp or have phones, though Aziz had one smuggled into him. Eventually, they got A/C, a gym, and some English classes, and a local court ruled that the camp had to allow the detainees phones and give them permission to leave the camp for trips into the nearby town.

"What I learned really is that it's this strange combination of both being … indefinite, there's nothing happening," says journalist Green. "But at the same time it's incredibly volatile. The men there are following the news incredibly closely about what's going to happen to them. And policies change a lot. Rumors spring up. Rules constantly change about what they are and are not allowed to do. It's a really troubling place."

Another message from Aziz: "I have to do what I could to protect myself and to keep myself, like, active. I'm an energetic person and I don't want to lose my energy. Sometime I play soccer and I do other different stuff. I do reading and writing, a little bit of everything because I just want to keep myself active and I don't want to, like, harm myself."

Aziz has told Green that he's seen some detainees cut themselves with razors, swallow nail clippers and laundry powder, drink shampoo, and jump from fences. Then there's the constant depressing feeling of never knowing when they'll be able to leave the island and be resettled somewhere else. "Everything about their lives is controlled," says Green. "They have to queue up for everything. They have to ask for toilet paper. They have to queue up for laundry powder. They basically can't make any decisions about their own lives and that has a really debilitating effect on people."

At one point, Green worried that he was being too intrusive in his audio messages to Aziz.

Message from Green: "I just want to say that if you don't want to answer any questions, don't worry about it. Or if you don't [feel] like answering, just tell me because I'll probably just keep asking questions until you tell me to leave you alone."

Message from Aziz: "Oh, come on Michael. Just ask me any question. I'm not the kind of man to say don't ask me or don't do that to me, man. I'm happy to answer any question."

Their conversation is not in real time, but in 30-second sound bursts. "It's really strange," says Green. "At various times, I'll look at my phone and there might be a hundred or 150 messages from Aziz and I'll spend the next few hours going through them. Not only that, they don't necessarily come through in the order that he sends them, which is really confusing. You know I feel like I know him so well but I don't get the pleasure of a free-flowing conversation."

In Australia, the offshore detention camps are deeply controversial. That's why the November 2016 agreement Australia struck with the outgoing Obama administration to resettle the refugees was so important. It provided a solution for both the detainees and the Australian government.

After Aziz and the other detainees heard about the deal, they were ecstatic.

Message from Aziz: "People were really happy. We are really happy. You know, kind of like someone who has lost hope and then finally they got it back. They got it back. They were so happy about the deal."

But then Donald Trump was elected and had that fateful phone call with Australia's Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull. After that came Trump's attempted ban on travel to the US from Muslim-majority nations, which targeted countries that are heavily represented among the detainees on Manus Island and Australia's other offshore camp on the island nation of Nauru.

Green messaged Aziz: "And so what do you think's going to happen next?"

Aziz responded: "I feel like this is kind of my destiny. After this prison, I may end up in another prison or end up in another place or I will have a better life or, I don't know what will happen. But from what I can see right now, I'm still having a dark future."

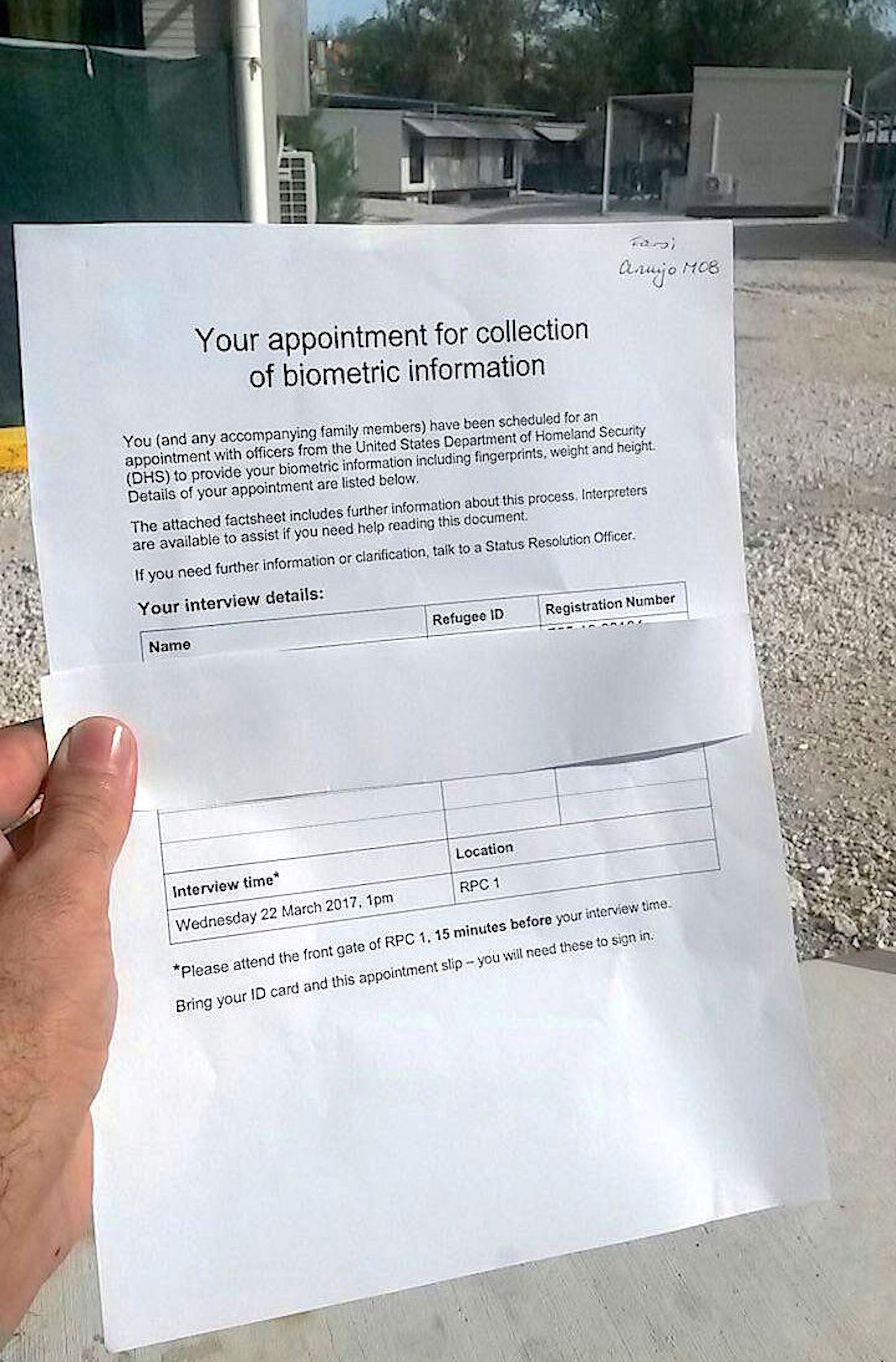

But there are signs that the United States may honor the Obama administration's agreement with Australia, after all. There are reports in the Australian press that Homeland Security officials have been on Manus doing prescreening, fingerprinting and photographing with some detainees. Those are preliminary steps in the process of resettlement to the US.

In response to a query from this reporter, a State Department official emailed: “Initial pre-screening interviews by a team from the Department of State’s Resettlement Support Center of refugees referred for resettlement consideration on Nauru and Manus have been completed as planned and DHS/USCIS interviews began on April 2. … The United States agreed to consider referrals from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) of refugees now residing in facilities in Nauru and Manus Island, Papua New Guinea (PNG). These refugees are of special interest to UNHCR and the United States is engaged in this resettlement effort on a humanitarian basis.”

But that's the State Department. One office that hasn't yet weighed in on the process, which seems to have already begun, is the White House.