When many South Koreans look at North Korea, they just don’t see much to fear. Shown here, a North Korean soldier waves to tourists on a Chinese boat sailing the Yalu River near the North Korean town of Sinuiju, April 2, 2017.

The 11th floor cafeteria at Sogang University has a fabulous view of downtown Seoul stretching all the way to the Han River.

The South Korean capital and surrounding area is home to nearly 25 million people. And the border with North Korea is only 30 miles away.

But for many students here, the dangers posed by the regime of Kim Jong-un seem like they are a whole world away.

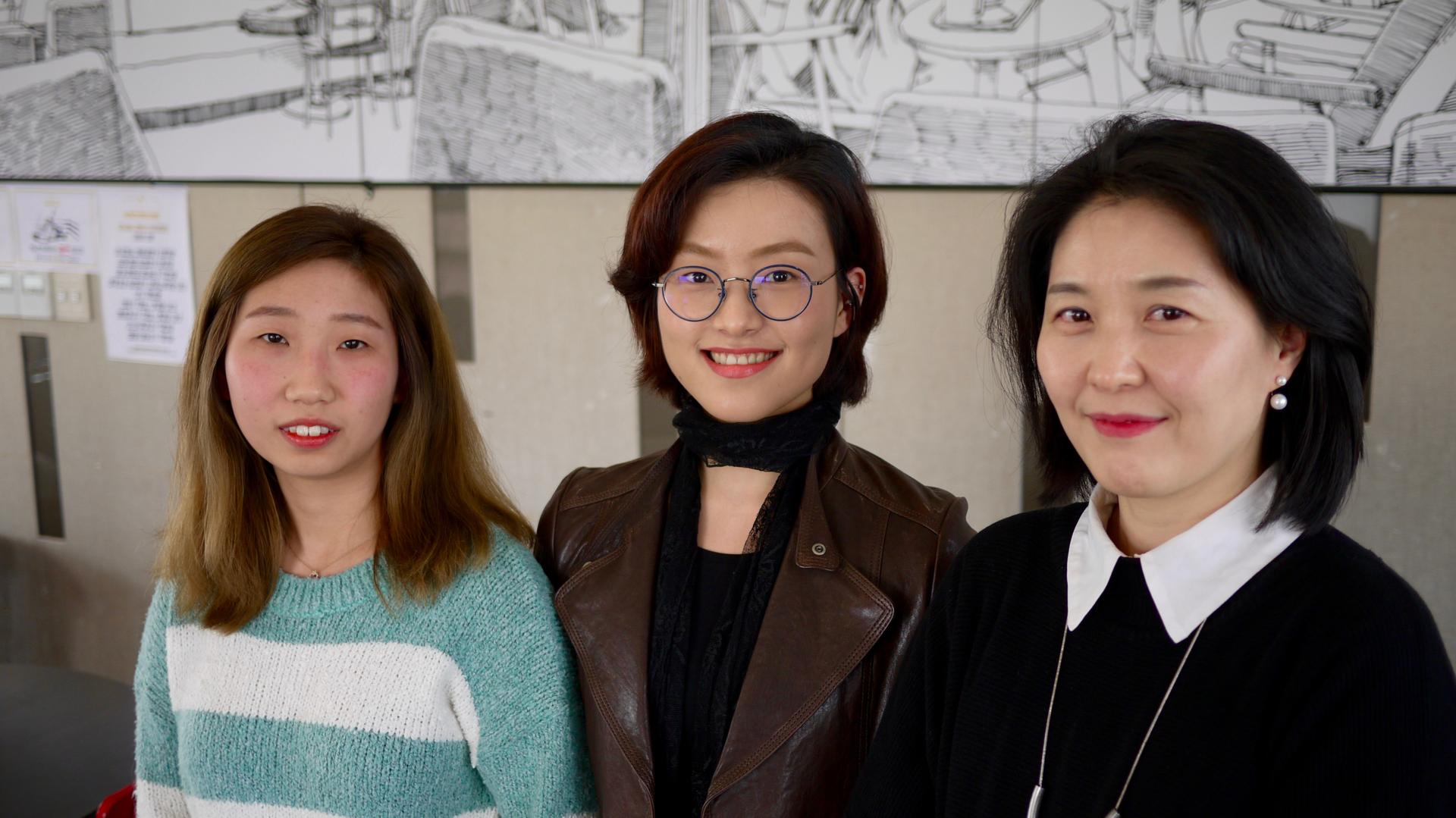

“There is a threat from there,” says Ko Young-sil, a 30-year-old psychology student enjoying a leisurely cafeteria lunch with two of her classmates. “But I have been hearing about the threat for a long time, and nothing ever happens. It’s just threats.”

Ko says she really doesn’t worry very much about North Korea, and neither do her two friends.

“They’re not our enemies, they’re our brothers and sisters,” Nam Ji-hye says about the North Koreans. “That’s what I’ve been taught.”

Voters in South Korea will go to the polls to elect a new president on May 9. And Nam says she will vote for a candidate who is friendly toward North Korea and wants to improve North-South relations.

Shim Joo-won, another psychology major, says she is a little more wary.

Shim, who is in her 40s, says she has a lot of confidence in the South Korean military and political leadership. And she doesn’t completely agree that the North Koreans are not the enemy.

“I remember the Cheonan,” she says, referring to the North Korean attack in 2010 on a South Korean navy ship that killed 46 sailors.

But again, Shim says North Korea, its military, missiles and even its nuclear weapons are things that she just doesn’t worry about very much in her daily life.

In between classes, I talk with an engineering student Un Hyo-jun in a designated campus smoking area. When I ask about his top concerns for the future, Un says it’s not North Korea.

“How to make a living,” says the 25-year-old, “how to get a job.”

Un says South Korea’s economy is so competitive that he is far more concerned about his own individual success than he is about the nation’s security.

On the basketball courts next to the smoking area, Paek Seung-ho tells me that North Korea’s nuclear weapons are a little scary to him. Paek is a 22-year-old chemical engineering student.

But the North Koreans know very well that deploying their nuclear weapons would mean the end of North Korea, he says.

In 2018, Paek will begin his two-year stint of mandatory military service in the South Korean army. He admits that North Korea is a sensitive issue, but he says he doesn’t really lose any sleep over fretting about it.

“When Obama was president, I had a lot of confidence, around 80 percent. But not so much now that Trump is president,” Paek says. “Trump doesn’t seem so willing to help out South Korea, and a lot of people here worry about that.”

Many older South Koreans feel differently, especially the folks at a protest camp in front of Seoul City Hall. The camp has been in place for weeks, as a show of support for the conservative ex-president, Park Geun-hye, who was impeached and is now in jail facing corruption charges.

There are no young people in sight at the protest camp. It’s mostly retirees, many of them military veterans like 77-year-old Lim San-mook, who is wearing a full army uniform and a red beret.

When this American reporter shows up, Lim stands at attention and offers a salute.

“Us old-timers, we experienced the Korean War. We are well aware of North Korea,” Lim says.

“But the youngsters, they don’t get it. They are more worried about their own future. We care more about national security.”

Related: President Trump, do you have a red line when it comes to North Korea?

Young people coming out of university here have good reasons to be worried about their prospects for personal success, says Kim Sung-kyung. She’s a professor at the University of North Korean Studies in Seoul. Besides, a divided Korean Peninsula between North and South has been a reality for more than 70 years, Kim says.

At the same time, Kim adds that there is a real danger in young South Koreans not taking the threats posed by North Korea seriously.

“If we don’t really recognize that danger, then we can’t make our plan. We can’t make our strategy to react to the danger. That’s one of very big problems with South Korea’s younger generation.”

“We have to be more prepared,” she says.

Related: A Korean adoptee meets his birth mother and winds up moving in with her