'RedadAlertas': an App that tells you where there are raids against immigrants.

No abra la puerta! Don't open the door!

That may be the No. 1 piece of advice activists have for the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants living in the United States, many of whom fear possible deportation. If the authorities come knocking without a proper warrant, US residents have a right not to open the door.

Advance notice of when an immigration raid on a workplace is about to go down certainly helps, too.

Now there's an app for that, focused on serving Spanish-speaking undocumented immigrants. It's called "RedadAlertas" — or RaidAlerts.

“Well, it doesn't work yet. It’s still in development," says Arizona-based software developer Celso Mireles. "But the way it would work, right now, is we want people to be able to sign up for alerts about raids near them and another group of people that will serve to report and verify the alerts."

Mireles is part of a team of open-source developers, technology activists and volunteers who are creating the crowdsourcing app.

The RedadAlertas project came out of discussions over the years among people involved in immigrant rights work. “We were brainstorming about how technology can help the undocumented community and this is one of those ideas that was born out of that conversation,” says Mireles.

The app focuses on identifying immigration checkpoints and possible workplace raids. And Mireles is anticipating that those kinds of raids will be happening more often.

Among President Donald Trump's executive orders from January calls for the hiring of 10,000 more immigration officials. At least one White House draft memo, obtained and publicly released by the Associated Press, showed the Department of Homeland Security considered deploying 100,000 National Guard troops to apprehend millions of undocumented immigrants in 11 US states. (The White House denied the report.) That kind of strategy would likely include raids on workplaces such as factories and farms that employ migrant workers, and sweeps of locations where day laborers meet up. It could also include traffic stops in which drivers are required to show a license and identification to pass. Mireles believes it is possible that immigration agents could conduct "blanket raids by walking neighborhoods."

"It's unprecedented now but I think there are a lot of unprecedented things happening," he says. "So this is really preparation for a much higher escalation of oppression of undocumented immigrants in the United States.”

Which is not to say Mireles is trying to make people afraid. He wants the information in the app to do the opposite. It will not, for example, alert people to individual home raids, where immigration agents arrive on doorsteps. That would not be helpful, he says, and "would probably only serve to increase the fear in the community which is what this app is just trying to quell.”

There may also be a legal risk incurred by developing software tools that allow undocumented immigrants to evade the law or impede law enforcement efforts. But so far, Mireles says the developers haven't received complaints.

“Nobody from ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] has contacted me and there are volunteer lawyers involved right now with the legal expertise in terms of privacy concerns and the legalities so I think we are well within the means of the law,” he says.

Users are already anxious to download the app, Mireles says. Some have suggested that the raid alerts should be available in languages besides Spanish, to be useful to as many immigrants as possible. About 13 percent of undocumented immigrants come from countries in Asia, according to estimates by the Migration Policy Institute. RedadAlertas is inviting volunteer translators to help expand access. It's also open-source software.

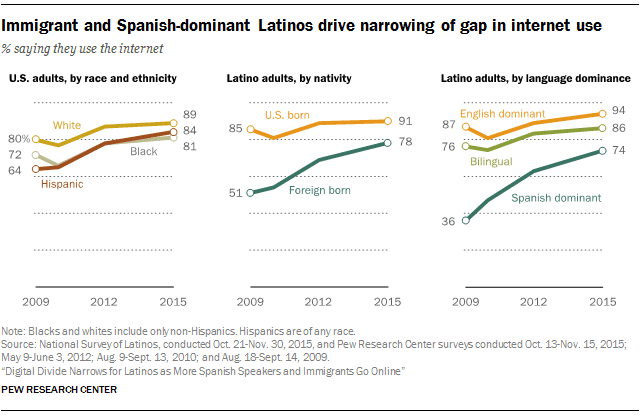

“Technology is advancing very quickly, and I'm interested in bringing that type of energy to the immigrant rights movement. We hear a lot of things like, ‘Well, you know, undocumented immigrants are loathe to adopt technology,’ and, ‘We need to think about accessibility.’ While some of that may be true, there are also studies that show, for example, that the Latino market is one of the early adopters,” he says.

“Of course we already see law enforcement using technology like a stingray to disable communications at peaceful protests,” says Mireles. But activists are accustomed to adapting. "I think we're trying to be aware of that as developers and just try to architect the tools so that it doesn't compromise and doesn't just create a nice tempting target for the government to infiltrate."

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!