Why the moons of Uranus are named after characters in Shakespeare

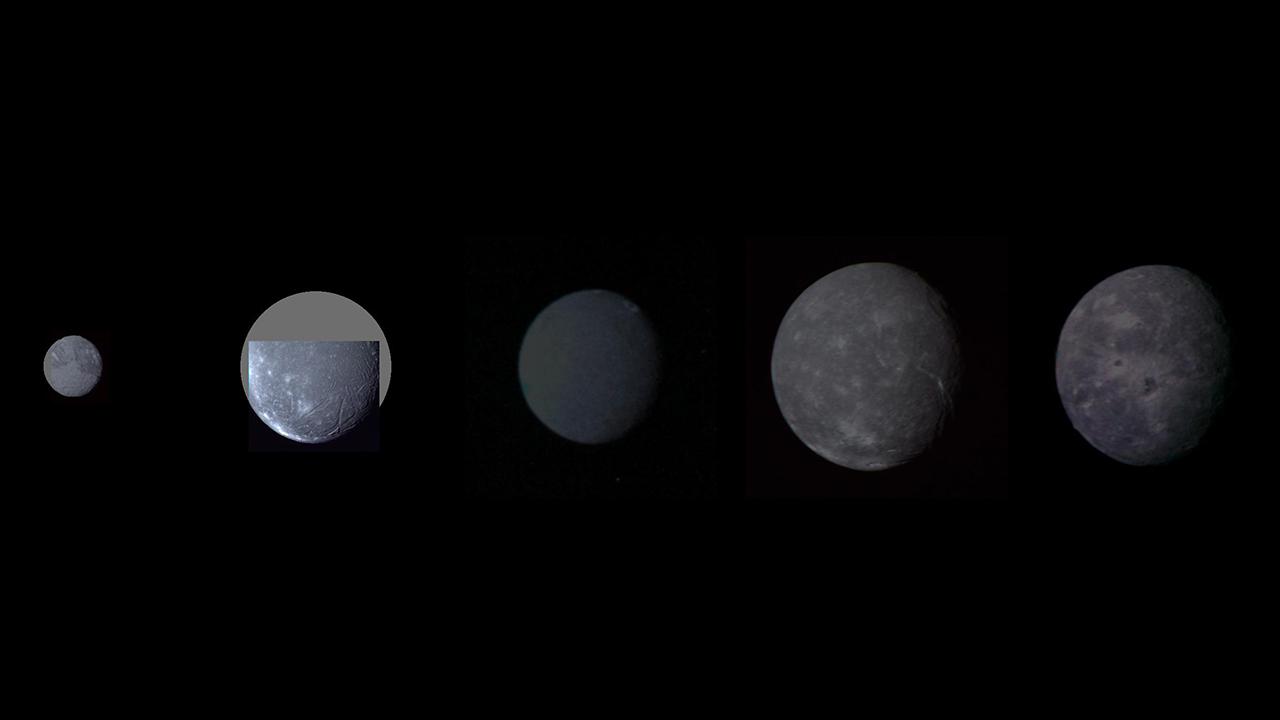

Five moons of Uranus are shown here: Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania and Oberon (from left to right).

"What’s in a name?" Shakespeare’s star-crossed Juliet famously wanted to know. And for those of us peering skyward, it’s a question for the ages: Where do celestial bodies get their names from?

There are constellations and planets christened after Greek and Roman gods. The craters on Mercury are artists and musicians, like Bach, John Lennon and Disney. And the moons of the planet Uranus — there are, impressively, 27 altogether — have literary ties — 25 of them relate to characters in Shakespeare’s plays.

For centuries, whoever discovered a celestial body usually had dibs on the naming rights. But when it comes to Uranus’ moons, details are murky about who exactly began doling out Shakespearean monikers.

The first two moons called Titania and Oberon, after the king and queen of the fairies in "A Midsummer Night’s Dream,"were discovered by William Herschel in 1787. (He was also a famous composer.) But Herschel simply referred to the satellites as "number one" and "number two," according to Cambridge University historian Michael Hoskin.

“I've read a huge amount of what Herschel wrote. And as far as I know, he’d never heard of Shakespeare,” Hoskin says.

But the Shakespeare references had to come from somewhere. One clue: Herschel’s son, John Herschel, also became an astronomer. He never discovered any moons, but he was a three-time president of the Royal Astronomical Society and one of Britain’s most prominent scientists in the 1850s. He also named Saturn’s moons. So, there’s reason to believe that when his contemporary William Lassell stumbled upon two more of Uranus’ moons in 1851, John Herschel may have had a hand in theirnaming, too.

In 1899, William Lassell’s daughter Jane Lassell told a reporter that the moons' names were given by Sir John Herschel, “to whom my father applied.” What that means for sure, we'll never know — she also said she lost their letters in a move — and Herschel never took the credit.

What is certain is this: Next to Titania and Oberon, the moons Lassell learned of became known as Ariel and Umbriel. (Umbriel is a figure in an Alexander Pope poem, and Ariel turns up as a character in both Shakespeare’s and Pope’s works. Pope is the literary exception to Shakespeare’s claim on Uranus’ moons.)

Continuing the tradition

Nevertheless, a clear Shakespearean precedent had been set by 1948, when the American astronomer Gerard Kuiper discovered a fifth moon of Uranus. “So you are now putting Kuiper among these prominent astronomers from the 19th and 18th centuries. This was really a big deal,” says Derek Sears, a scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center, who’s writing a biography of Kuiper. And true to tradition, Kuiper named the new moon Miranda, after a character in "The Tempest."

In the 1980s, NASA’s Voyager 2 probe found 10 new moons around Uranus. To label them, members of the Outer Planets Task Group in the International Astronomical Union’s Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature went back to the source: They started with Puck, from "A Midsummer Night’s Dream." The remaining moons sound like a character list out of the "Complete Works of Shakespeare." They include Cordelia, Ophelia, Bianca, Cressida, Desdemona, Juliet, Portia and Rosalind. Belinda, named for a Pope heroine, rounds out the leading ladies.

Two young astronomers, Brett Gladman and JJ Kavelaars, found two more moons in the mid-1990s, as they pored over images taken at the Palomar Observatory in San Diego. The images were created using a technique that made faint celestial bodies more visible. And when the question of what to name the moons was raised, Gladman — who knew his Shakespeare — had a ready answer.

“What's a Shakespearean character that lives in the dark? So Caliban leaped out right away, as you know, a creature emerging out of the dark,” Sears says.

Gladman and Kavelaars named the next moon Sycorax — in reference to "The Tempest," but also because Kavelaars loved the television show "Doctor Who." Several years later, they found two more moons, which had staggering, off-kilter orbits. They named them Stephano and Trinculo, after the drunken butler and drunken jester in "The Tempest."

It would, of course, be more practical to quit linking celestial discoveries with mythological heroes, rock stars or the odd mix of characters from Shakespeare and Pope. But according to Sears, sometimes simple has nothing to do with it.

“I do think most astronomers have some sort of a huge romantic streak,” he says. “It's just something about the right side of the brain of the astronomers that says, ‘Let's give them all names,’ you know — totally unnecessary, but we kind of like it.”

This article is based on a story that aired on PRI's Studio 360. The audio story was made possible with support from the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum and the Folger Shakespeare Library.