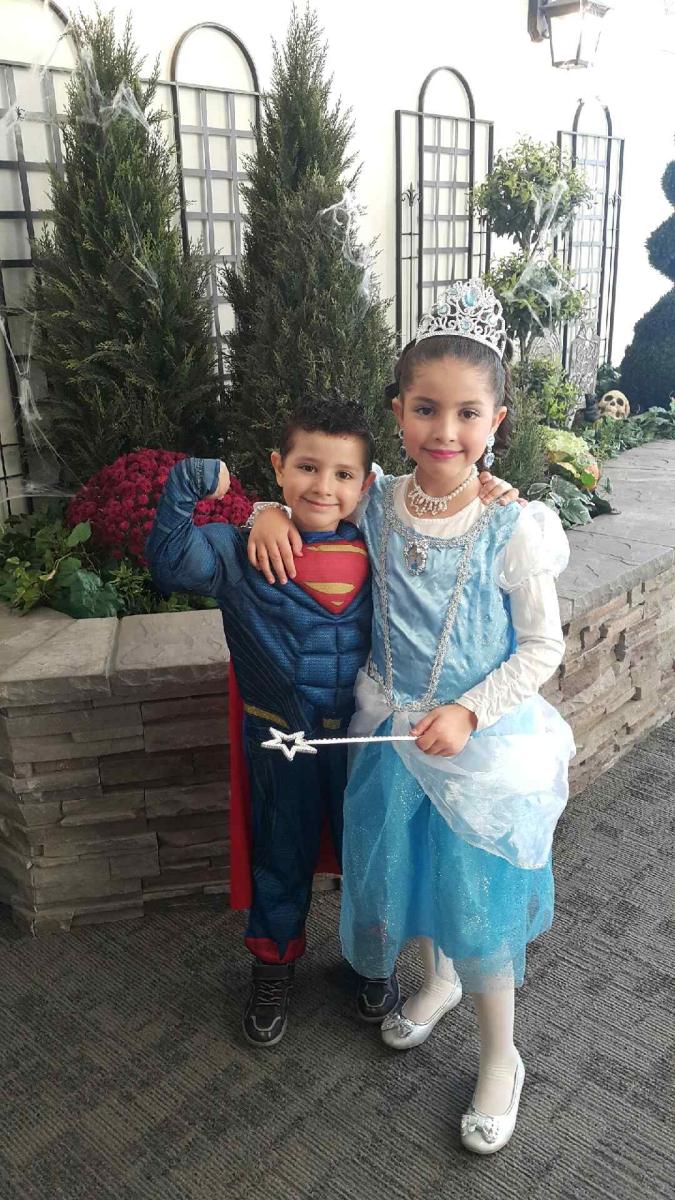

Hamzeh Mourad and his daughter, Houda. The Syrian family arrived in Canada last December with nothing but their clothes and $800.

More than 35,700 Syrian refugees have arrived in Canada since then-newly elected Prime Minister Justin Trudeau welcomed the first planeloads at Toronto’s Pearson International Airport last December.

Among the first to arrive were Hamzeh Mourad, his wife Ghader Bsmar and their two small children, Hoda, 7, and Feras, 5. Mourad wanted to support his family, so as soon as he learned to use the subway, he went straight to work.

Within six weeks, he was stocking shelves at a Middle Eastern grocery store in Toronto. Soon afterward, he took a second part-time job at a bakery that specializes in Indian sweets. The family now has enough money saved to buy a car so that Mourad can start a third job, driving for Uber.

Taking on a third job is an important move for Mourad and his family. Refugees receive financial support from either the Canadian government or private sponsors for a full year after they arrive.

But for the Mourads and thousands of other families who arrived early in the Canadian program, that support is now coming to an end.

Mourad sees a bright future ahead. He says he’s confident that working three jobs is just a temporary measure and that he’ll find better work once his English improves.

But for most of the refugees, the arrival of “month 13” in Canada will likely mean continued struggle. For many refugees, the first year of financial support barely covers the necessities. They can apply for social assistance once the official program ends.

Government studies show that up to 80 percent of refugees do that. But welfare payments are even lower and as recipients try to adapt to Canadian life, they can face significant financial difficulties.

Radwan Baranbo and his family arrived in Hamilton, Ontario last February. They are sponsored by the Canadian government, which pays them a monthly allowance to cover living expenses. Baranbo, 31, says the allowance barely pays for the essentials now. Welfare payments would be even lower.

His father, Ahmed Baranbo, has multiple sclerosis so the family has extra expenses. Radwan and his oldest sister, Khuloud, both have part-time jobs that pay the minimum wage — CA$11.40. They have to count every penny to make ends meet.

“It’s good if we have maybe 100 [Canadian dollars] on the 27th day of the month,” Radwan says. “This money that comes from the government, it covers just one month. Not extra things to save it.”

The Baranbos left Damascus in 2013 as Syria’s civil war intensified.

“We lost our home, we lost our houses and we lost our jobs, me and my sister and my dad, we lost everything there,” Radwan says.

They went to Jordan to try to build a new life. The Canadian government invited them to resettle here last February.

The Baranbos are a close-knit family, and education and self-improvement are a big priority. The father, Ahmed, 61, was a businessman in Damascus. Khuloud taught physics at Damascus University and hopes to pursue her PhD in Canada.

“I’d really like to be an expert or researcher in physics laboratories because I love experiments and physics,” she says.

He clearly enjoys learning English and is proud to say that he finally understands grammar. He says his future in Canada depends on it. As soon as his English is good enough, he wants to pursue an MBA and work in finance.

“If I have good English, I have a lot of choices. And I have good job. I will make lots good money,” Radwan says.

But as month 13 approaches, Radwan and Khuloud worry they may have to give up classes so they can support the family. Radwan says they don’t want to apply for welfare, because they’ve already taken enough from the government. He says he’s willing to take any job he has to, and that could mean the end of his English studies and possibly his ambitions.

“If I don’t have English I have [little] choices,” he says. “Maybe, like now in a restaurant, wash dishes. Not more, not higher position. I don’t like to stay at one level in life. I like to improve my life and improve my skill to be better.”

Canada has a program that allows private citizens to sponsor refugee families. And resettlement workers say that refugees who have private sponsors tend to settle in to their new home faster than government-sponsored arrivals. They say that’s because most private sponsorship groups provide ready-made connections to the community and an ongoing source of financial and social support.

A group of seven friends organized by Toronto residents Ashley McCall and her husband Chris Monahan have guided the Mourads every step of the way since the family arrived in Toronto last December.

McCall says everyone in the group was nervous about taking on the family.

“It was, you know, anxious that everything turn out and it felt like a big responsibility,” she says.

The Mourads escaped from Homs after Ghader’s youngest brother was killed by a roadside bomb. Their son, Feras, was just 2 years old, and had been diagnosed with leukemia, so they went to Jordan for medical care. They arrived in Canada with only their clothes and $800.

After meeting the family at Toronto’s international airport, McCall and Monahan took the Mourads to a friend’s home where they stayed over the Christmas holidays. Ghader says her family was nervous too but that they quickly settled in. The family is Muslim and it was their first Christmas. She says there were scented candles everywhere. When they woke up on Christmas morning they were surprised and delighted to find gifts from Santa Clause outside their door.

The sponsors have helped the Mourads with everything since. They enrolled the children in school, signed up the adults for English classes and helped Hamzeh find work.

Perhaps most importantly, they raised $43,000 (US$32,000) for the family. That was enough for Hamzeh could save his earnings, which will allow the family to live independently once the sponsorship ends this month.

She says that in Syria, family comes first and it was enough for her husband to work so she could stay home with the children. But life in Canada is more expensive and one salary isn’t enough. So she also has to work in order to provide a better future for the children.

It was a point of pride for Hamzeh to be able to support his family on his own. The sponsor group met with the couple several times to talk about the issue before Hamzeh finally relented. Starting in January, Ghader will earn her own paycheck as an Arabic teacher. Later in 2017, she’s going to college to study social work.

“I’m very happy because I feel like businesswoman,” Ghader says.

Things are looking up for the family. Hoda is earning good marks in school and Feras’ leukemia has gone into remission. After a year together, the Mourads and their sponsors say they feel more like family than friends and that even when the formal part of the sponsorship ends, they expect to remain close.

An earlier version of this story said that Ghader Bsmar’s sister was killed by a roadside bomb in Syria. It was her brother.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!