How a Lebanese immigrant helped pave the way for the study of Islam and Muslim culture in the US

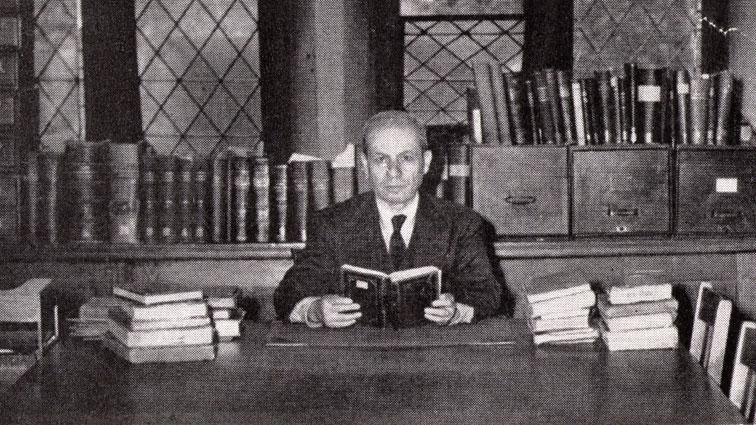

Philip K. Hitti, pictured at his desk at Princeton University in 1949. Hitti migrated to the US from Lebanon in 1913 and eventually helped create the first Near Eastern Studies program in the country.

By 2020, every high school student in California’s public and charter schools will be able to take at least one ethnic studies class.

It’s thanks to a bill that California state Rep. Luis Alejo and the California Latino Legislative Caucus. In doing so, they joined the ranks of educators, students, activists and elected officials who have pushed for courses that better reflect America’s changing demographics.

More about ethnic studies: California will soon provide ethnic studies classes for all high schoolers. Here’s why.

It’s not a new movement. At the height of the fight for civil rights in the 1960s, coalitions like the Third World Liberation Front argued for universities to introduce more courses on non-European histories and cultures, create better opportunities and services for students of color, and increase hiring of non-white faculty. Their efforts led to the country’s first College of Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University in 1969, and spurred the rise of ethnic studies programs across the country.

Yet the roots of the struggle to make the education system in the United States more inclusive along lines of race, ethnicity, religion, gender and sexuality go back earlier than the 1960s. One man — an immigrant who first came to the United States from Lebanon in 1913 — helped pave the way for greater diversity in American academics by pioneering the study of Islam in the United States. And it was all thanks to a broken arm.

Or at least that’s how Philip Khuri Hitti tells the story in his unpublished memoir, tucked away in his collection of personal and professional records that the Hitti family donated to the University of Minnesota’s Immigration History Research Center Archives.

Naturally, Hitti and his brother jumped onto the donkey as soon as they were out of their dad’s line of sight.

The fun and games lasted until the trio crossed paths with another donkey, throwing theirs into a stir, braying and jumping until the two boys fell to the ground. His brother was fine. Hitti, however, was not. The fall sent his bone through the skin of his right arm.

Hitti’s mother usually took care of the family’s medical needs. Repairing a compound fracture, however, was outside her skills. Village elders offered a range of remedies; one woman bent Hitti’s broken arm at the elbow and exposed it to steam rising from a brew of weeds and leaves. Hitti fainted. When he awoke, his wound remained.

Around that time, a graduate of the school of medicine at the Syrian Protestant College — known today as the American University of Beirut — was traveling through Shemlan and heard that a local boy required medical attention. His prognosis: Hitti’s arm had developed gangrene. He had to choose between death or the hospital.

After two surgeries and several months in recovery at a hospital about 15 miles away in Beirut, Hitti’s family held a meeting. Their prognosis: “Such a boy cannot make his living here; send him away to school.”

[[{“fid”:”167196″,”view_mode”:”default”,”type”:”media”,”link_text”:null,”field_deltas”:{},”attributes”:{“alt”:”black and white photo of a street corner with sign in Arabic and French: \”Rue du Dr. Philip Hitti” “,”height”:627,”width”:900,”class”:”media-element file-default”,”data-delta”:”2″},”fields”:{}}]]

Hitti had spent his earliest years as a student taking classes under an oak tree in the yard of his village’s church, and ended up in high school only as a side effect of a boyhood injury. College, he wrote, was “no nearer than the moon in pre-space days.”

But he excelled and, eventually, attended Syrian Protestant College just like the student who sent him to the hospital.

Hitti arrived in the US in 1913 and ultimately finished his Ph.D. at Columbia University in the summer of 1914. World War I temporarily interrupted his plans to return to Lebanon after graduating.

Hitti couldn’t help but feel out of place during his stint in wartime America. As far as he knew, he was the first “Near Easterner” to pursue a doctoral degree in the US. When he spoke with Americans who learned that the Lebanon he called home wasn’t in Pennsylvania or New Hampshire, but was a country on the other side of the world, Hitti felt like “a fossil on exhibit from some bygone age.”

He did return to Lebanon, though, in 1920 as a professor of Oriental history at the renamed American University of Beirut. A few years later, Princeton received a surge in funding for the study of the Middle East. One Princeton graduate left behind enough money to support scholarships and a library in the “ancient Oriental field.” Another donated enough Arabic books and manuscripts to start the Robert Garrett collection, which Hitti described as “one of the richest, if not the richest, of its kind connected with any university in the West or East.” In February 1926, Hitti returned to the US as an assistant professor of Semitic literature at Princeton.

Princeton may have had resources. But Hitti was perturbed by the university’s lack of coursework on Islam — the curriculum only offered classes that taught Islam as it related to Christianity and Judaism. As for language, Hitti explained there were no classes at Princeton or anywhere else in the US that focused on “Arabic for its own sake, as a carrier of a major world culture and as a key to one of the richest literatures.”

The courses Hitti taught were literally locked away in the ivory tower. When he first started teaching, the university tucked his classes away on the library’s edges, right next to patrons strolling the stacks and searching for books.

“The more I became aware of this giant blind spot in the American curriculum,” Hitti wrote, “the more I was determined to find a remedy for it.”

Hitti went to work. In addition to creating graduate courses in Arabic, Turkish and Persian languages, Hitti and the colleagues he recruited taught courses on the literature, history, religion, economics, sociology, politics and arts of the Near East.

When he tried to convince university administrators about “the merits of Islamic Studies,” Hitti remembered feeling like “Americans had inherited from Europeans a measure of political and religious prejudice against Islam.”

It took 20 years, but in the mid-1940s Hitti founded and became the first director of Princeton University’s Program in Near Eastern Studies.

In a 1971 interview in “Saudi Aramco World,” Hitti said that the deployment of Allied troops to North Africa and western Asia in World War II set the stage for increased interest in Middle Eastern studies — including in the US government, which began sending soldiers to Princeton so they could study Arabic. Tensions between Palestine and the emerging nation-state of Israel also played a key role in generating the financial and political support necessary for his program to get off the ground. Oil companies like Aramco and private philanthropic organizations like the Rockefeller Foundation, motivated by geopolitical maneuvering in the Middle East, helped foot the bill for Princeton’s Near Eastern Studies program.

Also: More American than apple pie, Muslims have been migrating to the US for centuries

Hitti played a major role in laying the foundation for the academic study of the Middle East in the US. But his legacy is not unproblematic. When discussing the Israel-Palestine conflict, he challenged Israel’s right to the land by suggesting their claim “had no more validity than a claim by Indians to the United States.” Scholar John Tofik Karam argued in an article in the “International Journal of Middle East Studies,” meanwhile, that Hitti’s role in helping create a program in Near Eastern studies owed too much to American political and military interests.

Nevertheless, nearly 40 years after his death in 1978, Hitti’s work to create more room for non-Eurocentric curriculum in American education is an important note in the ongoing struggle for ethnic and area studies in the US.

The Princeton program Hitti founded continues today. In addition, in March 2016, students and faculty gathered to protest budget cuts that threatened to undercut San Francisco’s College of Ethnic Studies.