These authors provide a glimpse of the buildings that were never built in New York City

The skyline of New York, which could look very different today.

New York City is home to one of the world’s most famous skylines. But for every landmark structure, there are dozens that never made it on the map. A floating airport on the Hudson River? Not quite. A gigantic dome protecting midtown Manhattan from bad weather? Never mind.

These ambitious plans are just a few of New York’s “never builts,” and these days, they exist only as discarded artistic renderings. Until now, that is: In a new book, “Never Built New York,” journalist Sam Lubell and his co-author, Greg Goldin, collect dozens of drawings and renderings that provide a glimpse of the New York skyline that was not to be — no easy task, given the subject matter.

“You can't go to the library and look for things that never happen because they don't get documented very often,” Lubell says. “But what you do is, you really get to know the history of people that build in the cities.”

Lubell and Goldin visited current firms to ask them what they knew of projects that never materialized. They also combed through archives around the country — over 30, Lubell says — that collect the work of New York’s architects, engineers and builders. “They've got incredible stuff that's just sitting in vaults, sitting in cold storage,” he adds.

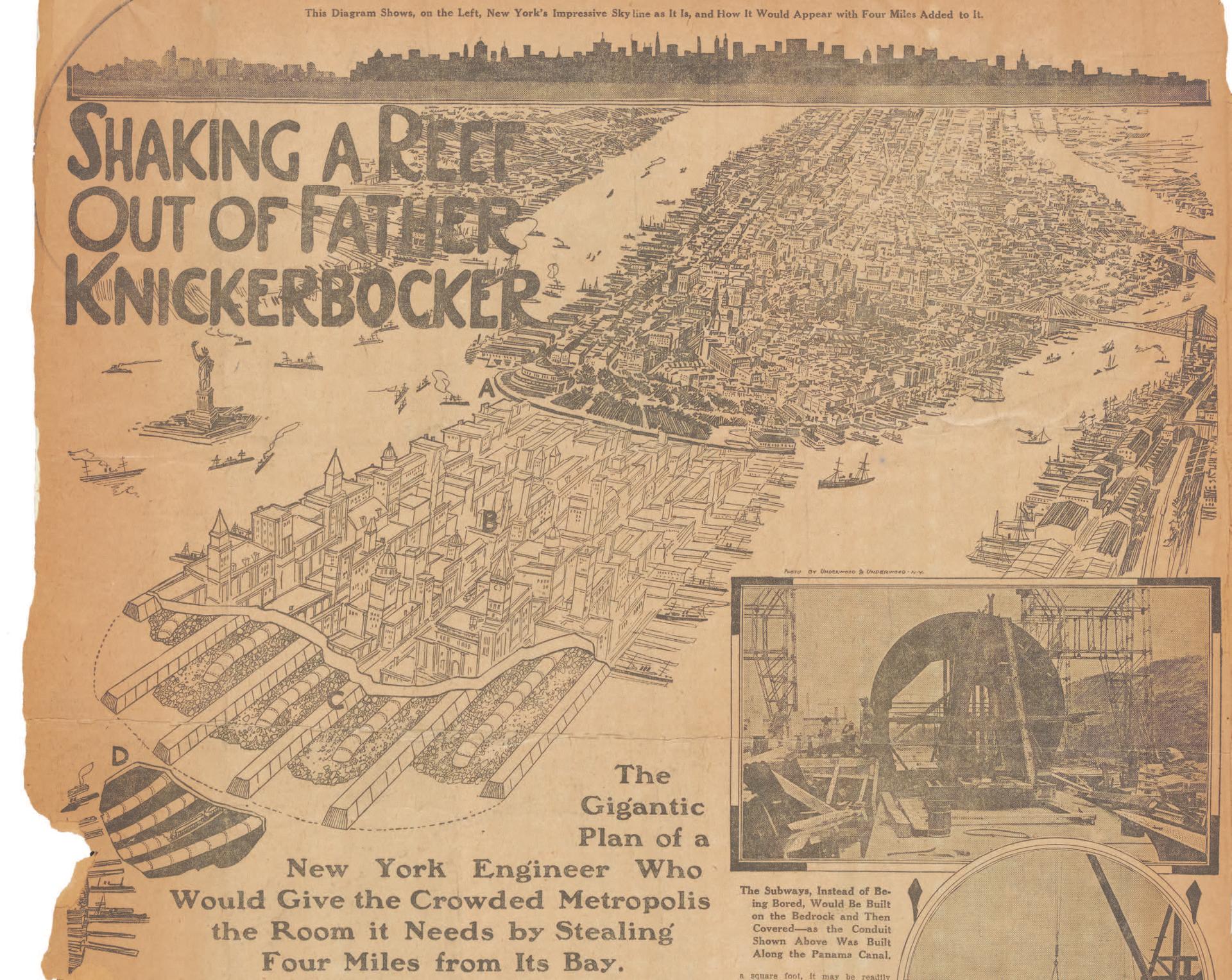

If constructed, many of the schemes and sketches in “Never Built New York” would have dramatically altered the fabric of the city. One project, proposed in 1911 by the civil engineer, T. Kennard Thomson, planned to extend Manhattan into New York Bay.

“The idea was basically to build another Manhattan off the tip of Manhattan … extending all the way down to basically Staten Island, swallowing Governor's Island, swallowing basically all of New York Bay,” Lubell says, carefully noting that Thomson “was not a crackpot by any means.”

In fact, Lubell adds that the city extension addressed the real anxieties of business groups in lower Manhattan: “[They] were scared that the momentum of business was moving northward toward midtown — which it was — and they were no longer going to be the center of things,” Lubell says. “But if things went south they'd remain the center.”

The extension project never materialized, but according to Lubell, it flitted in and out of the major newspaper headlines for decades. “This was not a joke of an idea,” he says. “And it was a time when ideas like this weren't … considered that far-fetched, amazingly.”

Although it’s hard to know the complete scope of New York’s “never builts,” Lubell says that one especially "fertile" period was the Great Depression, which he calls “the great collector of never-built projects.”

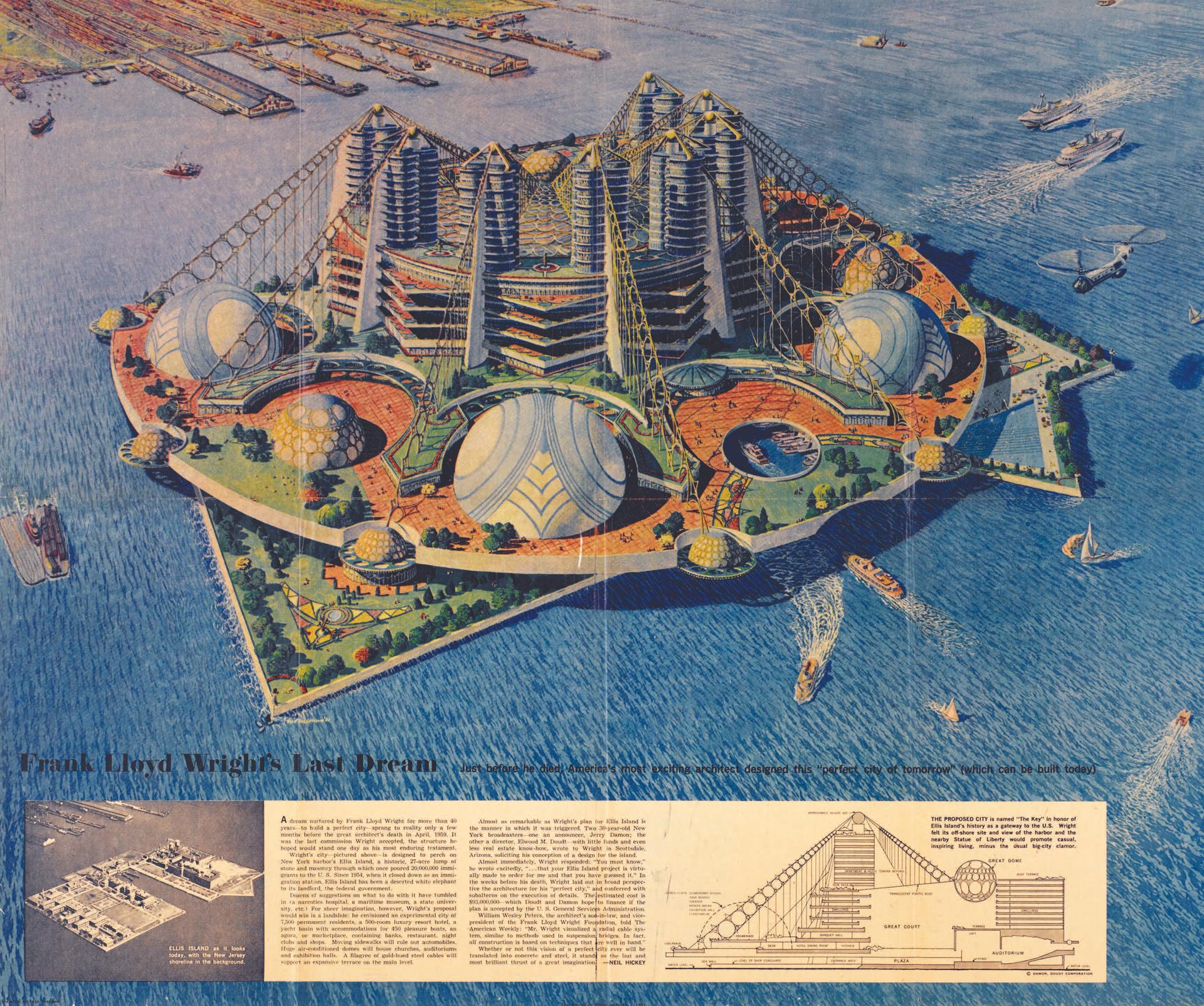

Another tide swelled several decades later, as the city dug deep to reinvent itself. During that period, for instance, we almost lost Ellis Island to Frank Lloyd Wright.

“The book shows these sites that you think are sort of sacrosanct,” Lubell says. “You know like, ‘Oh yeah, it's Ellis Island.’ And it's like, well actually, Ellis Island only served its purpose until the 1950s. And then the national government put it out to bid for developers.”

After proposals failed for a prison, and then a resort, Lubell says the highest bid came from a group that had hired Frank Lloyd Wright to redesign Ellis Island as a “city within a city.” Promotional materials for the development advertised “casual, inspired living, minus the usual big-city clamour,” but Ellis Island lived to tell its history.

Other famous sites, however, have been the subjects of repeated attempts on their architecture. Since the old Penn Station was torn down in the 1960s, Lubell says there have been more than half a dozen attempts to recreate it.

“And on the other side of the coin, we have more than half a dozen attempts to knock down Grand Central Station,” he notes. “Again, these things that you think are sacred in the city really weren't.”

Many of the ideas in “Never Built New York” came close to fruition. According to Lubell, one that didn’t was a plan by architect Buckminster Fuller to shelter midtown Manhattan with a giant dome. “That's not one that was particularly close, although it was very well-researched,” he says.

But the dome — and many of the other wild plans collected in “Never Built New York” — tells us something about the state of urban life as modern technology unfolded.

“It was a time when people really believed in the power of technology,” Lubell says. “And they thought, you know, we can do kind of anything. … We're building spaceships that go to the moon, why can't we build a dome over Manhattan to get rid of all this pollution, get rid of all the problems of weather?”

Today, things may not actually be so different — New Yorkers still have a preoccupation with making the most of their space. The Lowline, a proposed subterranean park beneath the Lower East Side, is one grand new idea.

“It's an interesting concept, which is how do you bring natural light, how do you bring new life into subterranean areas of Manhattan?” Lubell says. It’s the kind of project T. Kennard Thomson — would-be extender of Manhattan — might have supported a century earlier.

“It's again, rethinking how you live in Manhattan and how you use this limited space,” Lubell adds.

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Science Friday.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!