These black women were the mathematicians behind American spaceflight

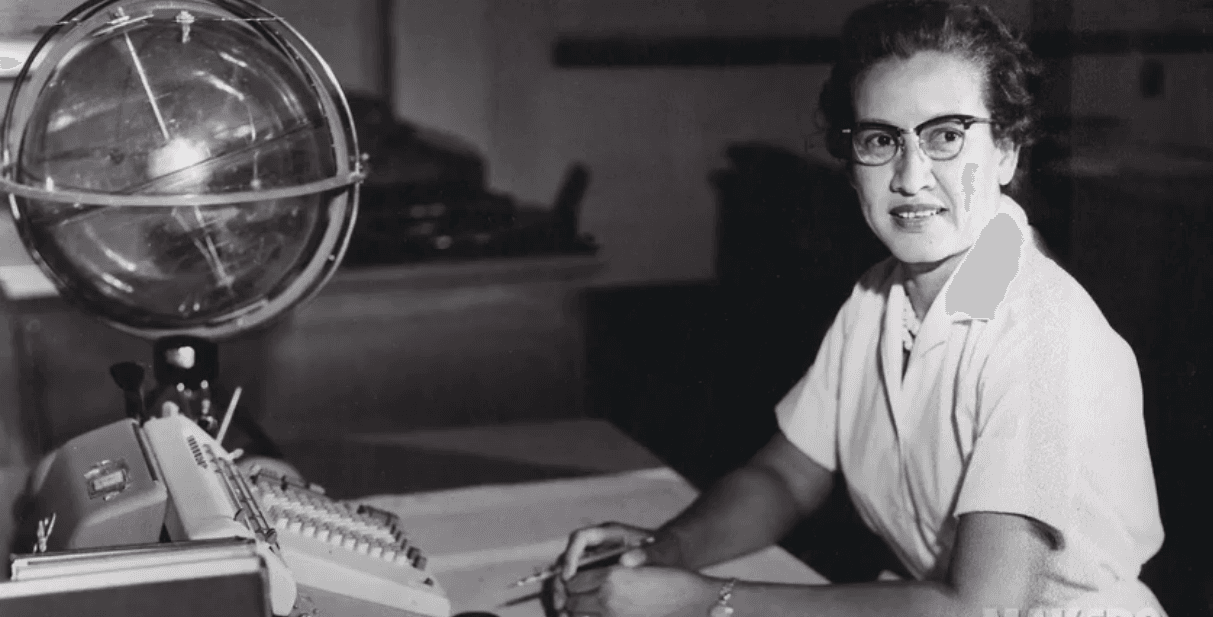

NASA research mathematician Katherine Johnson at her desk at Langley Research Center.

Before NASA, there was NACA — the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, headquartered at the Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. And before there were computers to analyze the NACA engineers’ data and double-check calculations, that job was done by “human computers,” or mathematicians hired to make sure the numbers were flight-ready.

In the 1940s, the first African American women entered the “computing pools,” as they were called, and dozens more joined in the decades following. Some continued on to become managers or engineers at NASA, and all made crucial — but often little-known — contributions to the math that put Americans in space. In her new book about Langley’s female mathematicians, “Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race,” Margot Lee Shetterly writes, “Growing up in Hampton, the face of science was brown like mine.”

It wasn’t until Shetterly was an adult that she realized what an anomaly Hampton’s scientific community had been. “Once I started asking questions like, ‘Well, how did they come to Langley? Why were there so many black women there?’ I just couldn't stop chasing the story,” she says.

NACA, which was tasked with building faster, more efficient airplanes, hired its first women “computers” in 1935. The engineers needed help processing large amounts of data their flight tests were generating.

“What they decided is, ‘What if we had a computing pool the same way we have a secretarial pool, and we’ll distribute this work to the members of the pool?’” Shetterly says. She adds that the first five women hired, all white, were paid less than their male counterparts, and their work freed engineers to focus on more research. From a management perspective, the program was a slam dunk — a fact only solidified as war became imminent.

“This is a time when airplanes are becoming more and more a part of the military,” Shetterly says. “And then on the eve of World War II, obviously the airplane was a very significant weapon of war.”

In 1941, at the urging of civil rights leaders like A. Philip Randolph, former President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, which banned discriminatory hiring practices in the defense industry. Two years later, the first black female mathematicians walked through the doors at Langley. They worked in the West Area computing office, in a remote wing of the facility that, as Shetterly writes, was “still more wilderness than anything resembling a workplace.” There were also segregated bathrooms and separate cafeteria tables at lunch. In the cafeteria, Miriam Mann, one of the early computers, intervened.

“Every day she took the sign that said ‘colored computers’ on the table,” Shetterly says. “She took it, she put it in her purse, and she took it home, just refusing to acknowledge the segregation, until one day the sign disappeared.”

The launch of Sputnik by the Soviet Union in 1957 ignited the space race and precipitated NACA’s metamorphosis into NASA — the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Other changes came about, as well. “The segregated era really lasted [until] the end of the NACA era,” Shetterly says.

In "Hidden Figures," Shetterly plots the career trajectories of four women along the curve of NACA’s shift toward space research. “They started their careers as math teachers. But they finished their careers at the Langley Research Center,” she says. “So it was possible to trace the course of their careers as they fought to get promoted, [and] as NASA started focusing on space and not just aeronautics.”

There was Dorothy Vaughan, who managed the all-black West Area Computing unit for nearly a decade. “She was actually the first African American manager, supervisor of any gender at Langley or at … all of what would become NASA,” Shetterly says.

Shetterly’s research also found that Mary Jackson, who became an engineer specializing in aerodynamics, was the first African American woman to be an engineer at NASA — and possibly in the entire United States.

Katherine Johnson calculated the trajectory for the Mercury mission that put the first American in space. And before John Glenn made his 1962 orbit of Earth, he asked that Johnson double-check the work of a very different type of computer: the electronic kind, which was, by then, in use at NASA.

“This [was] a very complicated mission that they had,” Shetterly says. “And one of the checklist items was having Katherine Johnson … take the raw numbers and run them through all of the equations that had been programmed into the [electronic] computer by hand, to make sure that the computer's results were the same as her results.”

Christine Darden, the former director of Langley’s Strategic Communications and Education office, also joined NASA in 1967 as a human computer. She entered a computing pool that was doing the tests for Apollo’s re-entry into the atmosphere, but seeing the work engineers were doing made her certain she wanted to be part of it — as an engineer.

“I had been in an all-black environment, pretty much until I came to NASA,” Darden says. “My entire education was segregated. And so when I got there, and I started thinking that I really wanted to pursue engineering and work as an engineer, and I wanted to go to school, one of the toughest decisions to make was I knew that the others in my class would be six or seven white males. And I would be the only female and the only black and that worried me a long time. And I finally just said, ‘I'm going to do it.’ And I did it.”

Darden enrolled in a doctoral program in mechanical engineering at George Washington University.

“Nobody spoke to me for a while. But after the first few weeks, and after a test or two, a couple of the guys came over and said, ‘Hey, you want to join our study group?’ And so it moved on from there, and I was focusing on doing what I was there to do.”

Darden’s first task as a NASA engineer was to develop a computer program that would help design an airplane that minimized "sonic boom" — to make it quieter in the air. She says she spent the next 15-odd years using that program to design, test and tweak models. If NASA develops an experimental "Supersonic X-plane," as it's called, its design could include her work from decades ago.

To Shetterly, stories like Darden’s are what make the saga of Langley’s African American human computers so compelling.

“In so many ways, these women's lives intersected other aspects of the 20th century, including the Civil Rights Movement [and the] Brown versus Board of [Education] decision,” she says. “So many aspects of their lives made for good science and good storytelling.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Science Friday.

The World is an independent newsroom. We’re not funded by billionaires; instead, we rely on readers and listeners like you. As a listener, you’re a crucial part of our team and our global community. Your support is vital to running our nonprofit newsroom, and we can’t do this work without you. Will you support The World with a gift today? Donations made between now and Dec. 31 will be matched 1:1. Thanks for investing in our work!