Lolita the Killer Whale is fed a fish by a trainer during a show at the Miami Seaquarium in Miami on January 21, 2015. Female killer whales are one of two mammals apart from humans to undergo menopause.

Menopause is a puzzle for biologists. Why would the female of a species cease to reproduce halfway through her life, when natural selection favors characteristics that help an individual's genes survive? A study of killer whales — one of only two mammals apart from humans to undergo menopause — is providing clues.

Granny is very spritely for a centenarian. When I finally catch sight of San Juan Island's local celebrity, she leaps clear out of the ocean to delighted gasps from everyone on my boat.

Granny is a killer whale, or orca.

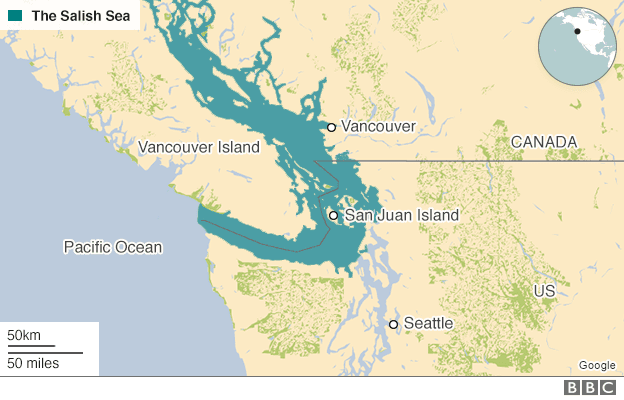

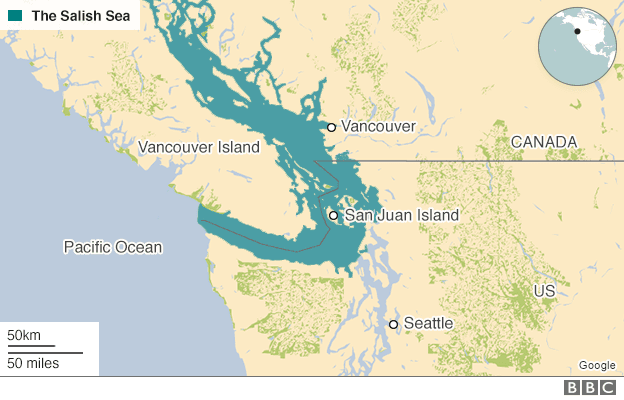

She lives in a coastal area of the North Pacific, close to Vancouver and Seattle, known as the Salish Sea. And while she is affectionately known as "Granny", her formal name is J2 — an alpha-numeric title that identifies her as a member of a population known as the Southern Resident orcas.

It is a clan of 83 killer whales in three distinct pods — J, K and L-pod — all of which return to this area of coastal Pacific waterways every summer. The network of inlets and calm inshore sea is peppered with forested and mountainous islands. Its beauty makes it popular with tourists – especially whale-watchers.

What many camera-clasping visitors want most is a glimpse of Granny — the oldest known living killer whale. Her age is an estimate, based on the age of her offspring when she and her pod were first studied in the early 1970s. She is at least 80, scientists say, and could be as old as 105.

I am here with a team of biologists who have a particular interest in her. They want to understand why J2, and the other females of this population, stop having babies in their 30s or 40s, even though they live so much longer. Biologists call it post-reproductive lifespan. We call it menopause.

Only three known mammals experience menopause — orcas, short-finned pilot whales and we humans. Even our closest ape cousins, chimpanzees, do not go through it. Their fertility peters out with age and, in the wild, they seldom live beyond childbearing years.

But female orcas and women evolved to live long, active, post-reproductive lives.

"From an evolutionary perspective, it's very difficult to explain," says Professor Darren Croft, who travels here from the UK's University of Exeter to study the whales.

"Why would an individual stop having their own offspring so early in life?"

Darwinian evolutionary theory says that any characteristic reducing an animal's chance of passing on its genes to the next generation will be edged out — the process of natural selection.

That has led some to argue that menopause in humans is a result of longer life, better health and better medical care. But, as well as painting a rather depressing image that post-menopausal women are simply alive beyond their evolutionarily prescribed time, that theory has been largely debunked — thanks, in part, to these orcas.

Obviously, medical care is not increasing their lifespan.

"So studying them in the wild could help us reveal some of the mystery of why menopause evolved," Croft says.

He and his fellow researcher Dr Dan Franks from the University of York, are investigating whether older post-reproductive females increase the survival chances of the rest of their family, and therefore of their own genes.

One part of their research is to plug the whales' vital life statistics – birth rates, death rates and odds of survival — into a Darwinian calculator to see if menopause is a net benefit.

It is a biological cost-benefit analysis. The question is whether an older female brings a measurable benefit to her existing family which outweighs the genetic cost of having no more babies.

But Croft and Franks also watch, very closely, how the killer whales behave.

Some of their latest insights came from analysing hundreds of hours of video footage of the whales going about their lives — chasing the salmon on which they depend for sustenance.

"We noticed that the old females would lead from the front — they're guiding their groups, their families, around to find food," says Croft.

Crucially, he and Franks also noticed that the older females took the lead more often during years when salmon supplies were low — suggesting that the pod might be reliant on their experience, their ecological knowledge.

"It's just like us," says Croft. "Before we had Google to ask where the shop was, if there was a drought or a famine, we would go to the elders in the community to find out where to find food and water.

"That kind of knowledge is accumulated over time — accumulated in individuals."

As we stand on the small research boat, Croft points out two dorsal fins, emerging briefly, like glistening black sails, from the surface of the water. They belong to a mother and an adult son, who appear to be working together to catch fish.

"That's an adult son, a 23-year-old male, staying right by his mother's side," Croft says.

His calculations have revealed just how much adult males depend on older matriarchs for their survival.

"From observations that had been collected on the whales, it appeared that the sons were dying shortly after their mothers died — they were being called 'mummy's boys,'" he says.

"So we looked at the [survival] data and found that if a mother dies, the risk of death of her sons is around eightfold the following year.

"And these are not immature males – these are 30-year-old, fully grown sons. She's doing something that's keeping those sons alive."

A mother killer whale's sons and daughters remain in her pod throughout their lives, and while the males leave briefly — to mix and mate with other females — they return, and are often seen swimming at their mother's side.

There have even been observations of older females sharing fish with their sons — literally feeding these full-grown "mummy's boys" with salmon.

So older females, it seems, work very hard to support their families, particularly their adult sons.

This makes good Darwinian sense, Croft argues. Sons mate with females from other pods, so those calves are the matriarch's genetic grandchildren, but it's a different pod that has the extra mouth to feed.

There is also evidence from the few remaining human hunter-gatherer societies that older females help their children, and their children's children, survive — a phenomenon dubbed the "grandmother effect."

University of Utah anthropologist Kristen Hawkes, who has studied the Hadza people of northern Tanzania since the 1980s, has observed how older women are particularly industrious, and spend more time foraging for their families than younger women.

"Kids in this Hadza hunter-gatherer population are also surprisingly active foragers at very young ages, but – as in all human populations – they can't fully feed themselves when they are weaned and still depended on food supplied by their mothers," she says.

"But when mothers had a new baby — the weaned youngsters depended on grandmothers. So we saw grandmothers' subsidies in action in those people, that would have likely operated in ancestral [human] populations."

Rather than foraging for regular sustenance, Hadza men go after big game, and when they make a kill, they share it with the whole community.

"Everybody comes to join in eating the mountain of meat," says Hawkes. "So most of it goes not to their own wives and kids but to others."

But despite the evidence of vital, industrious grandmothering among both orcas and humans, this benefit does not quite outweigh the cost — the cessation of reproduction — in Darren Croft's evolutionary equation.

There could be another factor driving the evolution of menopause, he thinks.

So the next thing the killer whale team has set out to examine is whether menopause helps the orcas survive by reducing the chance of mothers and daughters having babies at the same time – and by this means, perhaps, avoiding competition for resources such as food, or even parental care, a job that a pod's female orcas often share among themselves.

The ongoing Southern Resident census allows them to investigate this. They will be able to check, for example, whether calves have a better chance of survival when they have a post-menopausal grandmother.

And this could also get to the root of the drivers of human menopause.

Spending time with the killer whales of the Salish Sea, and focusing on what they have in common with humans, it's hard not to regret the way this population was treated by humans as recently as the 1970s.

The predictable habits of the Southern Residents made them an ideal target for capture, and for 10 years, between 1965 and 1975, killer whales were taken from the Salish Sea to supply marine parks.

Teams of hunters drove them into coves, separating the young animals they wanted from the rest of the pod. It's estimated that at least 13 animals were killed during the captures and 45 were taken into captivity, from a population of less than 100. It is an episode made infamous by the 2013 movie Blackfish.

Today, one Southern Resident remains in captivity — Lolita, a female who dwells in a tank at the Miami Seaquarium.

Now 50 years old, she has been kept in an enclosure at Miami Seaquarium for 46 years. She was dubbed the loneliest killer whale after her companion, Hugo, died in 1980 — she has had no contact with a member of her own species since then.

Lolita should now be returned to open water, according to campaigner Dr Jeffrey Ventre, a former SeaWorld trainer. "Her mother and siblings are still alive. She is an excellent candidate for release," he says. "Her case is particularly tragic because she has none of her own kind to interact with, and we know that these are the most social animals on the planet."

Ventre has published research comparing life expectancy in captive and wild orcas, which suggests that although survival rates have improved over the past 30 years, killer whales live longer in the wild.

But Miami Seaquarium has said it will not release Lolita because "it would be reckless to treat her life as and experiment and jeopardize her health and safety."

But the hunting and capture of the animals prompted a young zoologist, Ken Balcomb, to start observing and cataloguing the killer whales in 1976. His work exposed just how unsustainable the hunting of the whales was, and garnered the Southern Residents protection as endangered species.

He set up the Center for Whale Research on San Juan Island, and it now holds four decades of data on the births, deaths and social structures of the Southern Residents.

"We take identification pictures on everybody," Balcomb tells me.

"And we see who has new babies, and we see who's missing. And do this over and over all the years, and have kept very good track of the total population."

The population gradually recovered from the captures, but is now struggling once again, due to salmon shortages, pollution and noise in the orcas' coastal environment.

Although it was not designed for this purpose, Balcomb's unique 40-year-old dataset turned out to be a goldmine for the British evolutionary biologists studying the menopause.

And in the same unplanned way, Croft's findings have turned out to be of great interest to women writing about the menopause, a number of whom have contacted him.

One of them was Christa D'Souza, who published a book earlier this year about her own experience of menopause.

"I didn't want the book to be the anecdote of a West London woman, and I thought it would be interesting to look scientifically at why this happens to us," says D'Souza.

"The idea of women passing on information; the idea of wisdom with age – there's a beauty in that that is about something other than being able to reproduce.

"We complain, women of my age, of becoming invisible, and it's true – you realise how very much you're defined by sexuality. But I have a sense – galvanised by stories about the killer whales – that now is the time when you become the person you really want to be."

Croft says that talking to D'Souza and the other women opened his eyes to the wider impact of his work with the orcas.

"This very important role that old females have to play in killer whale society has highlighted the value of older individuals," he says.

"I'm delighted that the work is having this reach."

And while he can only watch from the surface, while so much of orca social life goes on beneath, he and Dan will return in the coming years. Hopefully, to be reunited with Granny once again and continue to reveal her evolutionary secrets.

This story was first published for the BBC Magazine. Hear Victoria Gill's documentary, "The Whale Menopause." PRI's The World is a co-production of the BBC World Service.

Menopause is a puzzle for biologists. Why would the female of a species cease to reproduce halfway through her life, when natural selection favors characteristics that help an individual's genes survive? A study of killer whales — one of only two mammals apart from humans to undergo menopause — is providing clues.

Granny is very spritely for a centenarian. When I finally catch sight of San Juan Island's local celebrity, she leaps clear out of the ocean to delighted gasps from everyone on my boat.

Granny is a killer whale, or orca.

She lives in a coastal area of the North Pacific, close to Vancouver and Seattle, known as the Salish Sea. And while she is affectionately known as "Granny", her formal name is J2 — an alpha-numeric title that identifies her as a member of a population known as the Southern Resident orcas.

It is a clan of 83 killer whales in three distinct pods — J, K and L-pod — all of which return to this area of coastal Pacific waterways every summer. The network of inlets and calm inshore sea is peppered with forested and mountainous islands. Its beauty makes it popular with tourists – especially whale-watchers.

What many camera-clasping visitors want most is a glimpse of Granny — the oldest known living killer whale. Her age is an estimate, based on the age of her offspring when she and her pod were first studied in the early 1970s. She is at least 80, scientists say, and could be as old as 105.

I am here with a team of biologists who have a particular interest in her. They want to understand why J2, and the other females of this population, stop having babies in their 30s or 40s, even though they live so much longer. Biologists call it post-reproductive lifespan. We call it menopause.

Only three known mammals experience menopause — orcas, short-finned pilot whales and we humans. Even our closest ape cousins, chimpanzees, do not go through it. Their fertility peters out with age and, in the wild, they seldom live beyond childbearing years.

But female orcas and women evolved to live long, active, post-reproductive lives.

"From an evolutionary perspective, it's very difficult to explain," says Professor Darren Croft, who travels here from the UK's University of Exeter to study the whales.

"Why would an individual stop having their own offspring so early in life?"

Darwinian evolutionary theory says that any characteristic reducing an animal's chance of passing on its genes to the next generation will be edged out — the process of natural selection.

That has led some to argue that menopause in humans is a result of longer life, better health and better medical care. But, as well as painting a rather depressing image that post-menopausal women are simply alive beyond their evolutionarily prescribed time, that theory has been largely debunked — thanks, in part, to these orcas.

Obviously, medical care is not increasing their lifespan.

"So studying them in the wild could help us reveal some of the mystery of why menopause evolved," Croft says.

He and his fellow researcher Dr Dan Franks from the University of York, are investigating whether older post-reproductive females increase the survival chances of the rest of their family, and therefore of their own genes.

One part of their research is to plug the whales' vital life statistics – birth rates, death rates and odds of survival — into a Darwinian calculator to see if menopause is a net benefit.

It is a biological cost-benefit analysis. The question is whether an older female brings a measurable benefit to her existing family which outweighs the genetic cost of having no more babies.

But Croft and Franks also watch, very closely, how the killer whales behave.

Some of their latest insights came from analysing hundreds of hours of video footage of the whales going about their lives — chasing the salmon on which they depend for sustenance.

"We noticed that the old females would lead from the front — they're guiding their groups, their families, around to find food," says Croft.

Crucially, he and Franks also noticed that the older females took the lead more often during years when salmon supplies were low — suggesting that the pod might be reliant on their experience, their ecological knowledge.

"It's just like us," says Croft. "Before we had Google to ask where the shop was, if there was a drought or a famine, we would go to the elders in the community to find out where to find food and water.

"That kind of knowledge is accumulated over time — accumulated in individuals."

As we stand on the small research boat, Croft points out two dorsal fins, emerging briefly, like glistening black sails, from the surface of the water. They belong to a mother and an adult son, who appear to be working together to catch fish.

"That's an adult son, a 23-year-old male, staying right by his mother's side," Croft says.

His calculations have revealed just how much adult males depend on older matriarchs for their survival.

"From observations that had been collected on the whales, it appeared that the sons were dying shortly after their mothers died — they were being called 'mummy's boys,'" he says.

"So we looked at the [survival] data and found that if a mother dies, the risk of death of her sons is around eightfold the following year.

"And these are not immature males – these are 30-year-old, fully grown sons. She's doing something that's keeping those sons alive."

A mother killer whale's sons and daughters remain in her pod throughout their lives, and while the males leave briefly — to mix and mate with other females — they return, and are often seen swimming at their mother's side.

There have even been observations of older females sharing fish with their sons — literally feeding these full-grown "mummy's boys" with salmon.

So older females, it seems, work very hard to support their families, particularly their adult sons.

This makes good Darwinian sense, Croft argues. Sons mate with females from other pods, so those calves are the matriarch's genetic grandchildren, but it's a different pod that has the extra mouth to feed.

There is also evidence from the few remaining human hunter-gatherer societies that older females help their children, and their children's children, survive — a phenomenon dubbed the "grandmother effect."

University of Utah anthropologist Kristen Hawkes, who has studied the Hadza people of northern Tanzania since the 1980s, has observed how older women are particularly industrious, and spend more time foraging for their families than younger women.

"Kids in this Hadza hunter-gatherer population are also surprisingly active foragers at very young ages, but – as in all human populations – they can't fully feed themselves when they are weaned and still depended on food supplied by their mothers," she says.

"But when mothers had a new baby — the weaned youngsters depended on grandmothers. So we saw grandmothers' subsidies in action in those people, that would have likely operated in ancestral [human] populations."

Rather than foraging for regular sustenance, Hadza men go after big game, and when they make a kill, they share it with the whole community.

"Everybody comes to join in eating the mountain of meat," says Hawkes. "So most of it goes not to their own wives and kids but to others."

But despite the evidence of vital, industrious grandmothering among both orcas and humans, this benefit does not quite outweigh the cost — the cessation of reproduction — in Darren Croft's evolutionary equation.

There could be another factor driving the evolution of menopause, he thinks.

So the next thing the killer whale team has set out to examine is whether menopause helps the orcas survive by reducing the chance of mothers and daughters having babies at the same time – and by this means, perhaps, avoiding competition for resources such as food, or even parental care, a job that a pod's female orcas often share among themselves.

The ongoing Southern Resident census allows them to investigate this. They will be able to check, for example, whether calves have a better chance of survival when they have a post-menopausal grandmother.

And this could also get to the root of the drivers of human menopause.

Spending time with the killer whales of the Salish Sea, and focusing on what they have in common with humans, it's hard not to regret the way this population was treated by humans as recently as the 1970s.

The predictable habits of the Southern Residents made them an ideal target for capture, and for 10 years, between 1965 and 1975, killer whales were taken from the Salish Sea to supply marine parks.

Teams of hunters drove them into coves, separating the young animals they wanted from the rest of the pod. It's estimated that at least 13 animals were killed during the captures and 45 were taken into captivity, from a population of less than 100. It is an episode made infamous by the 2013 movie Blackfish.

Today, one Southern Resident remains in captivity — Lolita, a female who dwells in a tank at the Miami Seaquarium.

Now 50 years old, she has been kept in an enclosure at Miami Seaquarium for 46 years. She was dubbed the loneliest killer whale after her companion, Hugo, died in 1980 — she has had no contact with a member of her own species since then.

Lolita should now be returned to open water, according to campaigner Dr Jeffrey Ventre, a former SeaWorld trainer. "Her mother and siblings are still alive. She is an excellent candidate for release," he says. "Her case is particularly tragic because she has none of her own kind to interact with, and we know that these are the most social animals on the planet."

Ventre has published research comparing life expectancy in captive and wild orcas, which suggests that although survival rates have improved over the past 30 years, killer whales live longer in the wild.

But Miami Seaquarium has said it will not release Lolita because "it would be reckless to treat her life as and experiment and jeopardize her health and safety."

But the hunting and capture of the animals prompted a young zoologist, Ken Balcomb, to start observing and cataloguing the killer whales in 1976. His work exposed just how unsustainable the hunting of the whales was, and garnered the Southern Residents protection as endangered species.

He set up the Center for Whale Research on San Juan Island, and it now holds four decades of data on the births, deaths and social structures of the Southern Residents.

"We take identification pictures on everybody," Balcomb tells me.

"And we see who has new babies, and we see who's missing. And do this over and over all the years, and have kept very good track of the total population."

The population gradually recovered from the captures, but is now struggling once again, due to salmon shortages, pollution and noise in the orcas' coastal environment.

Although it was not designed for this purpose, Balcomb's unique 40-year-old dataset turned out to be a goldmine for the British evolutionary biologists studying the menopause.

And in the same unplanned way, Croft's findings have turned out to be of great interest to women writing about the menopause, a number of whom have contacted him.

One of them was Christa D'Souza, who published a book earlier this year about her own experience of menopause.

"I didn't want the book to be the anecdote of a West London woman, and I thought it would be interesting to look scientifically at why this happens to us," says D'Souza.

"The idea of women passing on information; the idea of wisdom with age – there's a beauty in that that is about something other than being able to reproduce.

"We complain, women of my age, of becoming invisible, and it's true – you realise how very much you're defined by sexuality. But I have a sense – galvanised by stories about the killer whales – that now is the time when you become the person you really want to be."

Croft says that talking to D'Souza and the other women opened his eyes to the wider impact of his work with the orcas.

"This very important role that old females have to play in killer whale society has highlighted the value of older individuals," he says.

"I'm delighted that the work is having this reach."

And while he can only watch from the surface, while so much of orca social life goes on beneath, he and Dan will return in the coming years. Hopefully, to be reunited with Granny once again and continue to reveal her evolutionary secrets.

This story was first published for the BBC Magazine. Hear Victoria Gill's documentary, "The Whale Menopause." PRI's The World is a co-production of the BBC World Service.