9 of the best nonfiction comics from around the world

Comic books bridge continents.

Superman spinoffs are a hit in China; Japanese manga trickled into American culture through Frank Miller's Ronin and even the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. The Adventures of Tintin was translated from French into more than 50 languages.

But it's not just in the world of entertainment that visual storytelling circles the globe. Alongside the superhero franchises and funny pages, a thriving genre of nonfiction comics has created new audiences and new appreciation for everything from war reporting to memoir. Here are nine modern classics whose intricate illustrations have shaped the form.

1. Yoshihiro Tatsumi, “A Drifting Life”

“A Drifting Life” uses intimate and lighthearted frames to trace Tatsumi's growth as an artist — and in the process, he builds an intricate history of manga as a form.

2. Lynda Barry, “One! Hundred! Demons!”

Lynda Barry's "One! Hundred! Demons!" is what you get when you mix together a few cups of fact, a spoonful of fiction and innumerable cups of coffee. Barry says her memoir was inspired by a handscoll painted by a Zen monk named Hakuin Ekaku, in 16th century Japan.

Her own colorful variant on the handscroll, which falls somewhere between comic and collage, tells tiny stories of growing up that are both playful and profound.

3. Riad Sattouf, “The Arab of the Future”

“In 1980, I was two years old, and I was perfect,” Sattouf declares.

Through a child's eyes, Sattouf builds a backdrop for the Arab world we know today. In Syria, where young men style their hairs like characters in Grease, Sattouf writes: “Using their hands, the women began to eat the remains of the meal eaten by the men in the next room.”

In Tripoli, houses belong to whomever moves in, but families have to wait in food lines for baked beans and green bananas. After the disappointments of the Arab Spring, it's easy to be cynical about the history of the Middle East. But Sattouf chooses the more challenging approach — to look for hope and humor where there's not much to be found.

4. Art Spiegelman, “Maus”

"Maus" helped nonfiction comics go mainstream when, in 1992, it became the first graphic novel to with the Pulitzer Prize. In simple black-and-white strips that were serialized for more than a decade, Spiegelman tries to make sense of his Jewish father's memories of the Holocaust.

He wryly casts Jews as mice and Germans as cats, as if World War II were a horrifying version of Tom and Jerry. As Spiegelman alternates between his present and his father's past, he sketches out his own complex relationship to his roots.

5. Marjane Satrapi, “Persepolis”

In the next frame, we see dozens of people trying to pedal an unwieldy five-wheeled contraption. Needless to say, it's not going anywhere.

Satrapi's simple black-and-white illustrations capture a turbulent history with surprising depth. In one historical panel, British colonial rulers — embodied by a bald man sipping liqueur and a greasy man smoking a pipe — plot the takeover of Iran. In another panel, after the execution of one of her heroes, Satrapi argues bitterly with God.

She can forsake her faith, but for most of her childhood, she can't escape her home. And since she can't leave, she starts to love Iran. “This old and great civilization has been discussed mostly in connection with fundamentalism, fanaticism, and terrorism,” she writes in her introduction. Persepolis changes that.

6. Joe Sacco, “The Fixer and Other Stories”

“The Fixer” is a war story set in peacetime. In 2001, Joe Sacco traveled to Sarajevo, hoping to find the interpreter who'd helped him during the Yugoslav Wars. By this time, correspondents had cleared out and soldiers had become civilians. Memories of atrocity were starting to slip beneath the surface — but Sacco's book excavates them.

During one flashback, Sacco portrays his wartime arrival to Sarajevo, and it's styled like film noir: hulking architecture, empty streets, long shadows. In a surreal scene at the Holiday Inn, the concierge points to the hotel on a city map.

“This is the front line,” she says. “Don't ever walk here.”

Then, in the lobby, Sacco meets his fixer.

7. Henrik Rehr, “Terrorist: Gavrilo Princip, the Assassin Who Ignited World War I”

Rehr's graphic novel paints a sympathetic portrait of a terrorist — which, in our day and age, makes it both provocative and timely. Rehr, a Danish artist now based in New York, is no stranger to modern terrorism: During the September 11 attacks, his apartment was less than two blocks from the World Trade Center towers.

But in “Terrorist,” Rehr takes his readers a century back in time, starting with a quote from Otto von Bismarck: “Europe today is a powder keg.”

In dark, atmospheric sketches, Rehr depicts the explosive start to World War I — the assassination of Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. He tries to explain why Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb, embraced anarchy in the fight against the Ottoman Turks and the Austro-Hungarian monarchy.

By focusing on Princip, Rehr examines what we'd today call radicalization — and for the most part, he succeeds in helping humanize an assassin. As Rehr writes in the afterword: “Empathy for both the murderer and his victim came easily to me.”

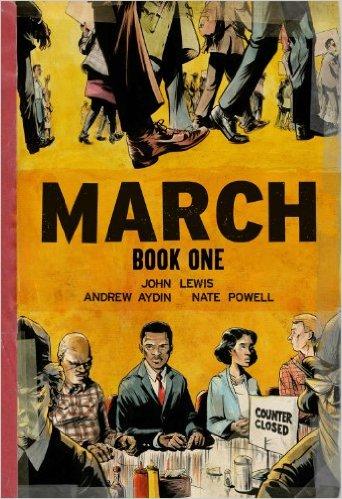

8. John Lewis, Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell, “March”

Growing up, Lewis encounters persecution everywhere. During a road trip to Ohio, he and his uncle have to carefully avoid segregated restaurants; after he goes to college in Nashville, student groups demand to be served at whites-only lunch counters. The book depicts the brutality, prison time and legal battles endured by Lewis and his fellow marchers, long before he became Congressman John Lewis of Georgia.

This year, “March” won three Eisner Awards, which are often called the Oscars of the comic books world. In the era of Black Lives Matter — and the year that Lewis led a congressional sit-in to demand gun control legislation — it's a timely and powerful book.

Two subsequent volumes also have become best-sellers.

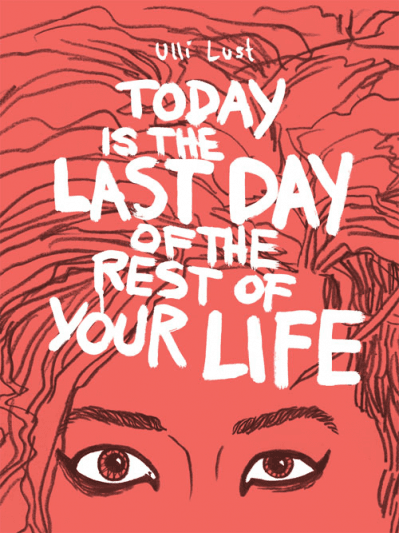

9. Ulli Lust, “Today is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life”

Many scenes take place in bars or brothels and delve into a gritty leftist subculture.

“Today is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life” is a testament not only to how boldly Lust traveled, but also how far she's come as an artist. Soon after the road trip in her book, Lust became a single mother; she tried to make a living by publishing books she wrote for her son.

Only after three children's books did she start studying illustration in Berlin.

A shortened version of this list originally appeared on Longreads. Do you have a favorite on this list, or want to tell us about a book you think belongs here? Let us know in the comments section.

Comic books bridge continents.

Superman spinoffs are a hit in China; Japanese manga trickled into American culture through Frank Miller's Ronin and even the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. The Adventures of Tintin was translated from French into more than 50 languages.

But it's not just in the world of entertainment that visual storytelling circles the globe. Alongside the superhero franchises and funny pages, a thriving genre of nonfiction comics has created new audiences and new appreciation for everything from war reporting to memoir. Here are nine modern classics whose intricate illustrations have shaped the form.

1. Yoshihiro Tatsumi, “A Drifting Life”

“A Drifting Life” uses intimate and lighthearted frames to trace Tatsumi's growth as an artist — and in the process, he builds an intricate history of manga as a form.

2. Lynda Barry, “One! Hundred! Demons!”

Lynda Barry's "One! Hundred! Demons!" is what you get when you mix together a few cups of fact, a spoonful of fiction and innumerable cups of coffee. Barry says her memoir was inspired by a handscoll painted by a Zen monk named Hakuin Ekaku, in 16th century Japan.

Her own colorful variant on the handscroll, which falls somewhere between comic and collage, tells tiny stories of growing up that are both playful and profound.

3. Riad Sattouf, “The Arab of the Future”

“In 1980, I was two years old, and I was perfect,” Sattouf declares.

Through a child's eyes, Sattouf builds a backdrop for the Arab world we know today. In Syria, where young men style their hairs like characters in Grease, Sattouf writes: “Using their hands, the women began to eat the remains of the meal eaten by the men in the next room.”

In Tripoli, houses belong to whomever moves in, but families have to wait in food lines for baked beans and green bananas. After the disappointments of the Arab Spring, it's easy to be cynical about the history of the Middle East. But Sattouf chooses the more challenging approach — to look for hope and humor where there's not much to be found.

4. Art Spiegelman, “Maus”

"Maus" helped nonfiction comics go mainstream when, in 1992, it became the first graphic novel to with the Pulitzer Prize. In simple black-and-white strips that were serialized for more than a decade, Spiegelman tries to make sense of his Jewish father's memories of the Holocaust.

He wryly casts Jews as mice and Germans as cats, as if World War II were a horrifying version of Tom and Jerry. As Spiegelman alternates between his present and his father's past, he sketches out his own complex relationship to his roots.

5. Marjane Satrapi, “Persepolis”

In the next frame, we see dozens of people trying to pedal an unwieldy five-wheeled contraption. Needless to say, it's not going anywhere.

Satrapi's simple black-and-white illustrations capture a turbulent history with surprising depth. In one historical panel, British colonial rulers — embodied by a bald man sipping liqueur and a greasy man smoking a pipe — plot the takeover of Iran. In another panel, after the execution of one of her heroes, Satrapi argues bitterly with God.

She can forsake her faith, but for most of her childhood, she can't escape her home. And since she can't leave, she starts to love Iran. “This old and great civilization has been discussed mostly in connection with fundamentalism, fanaticism, and terrorism,” she writes in her introduction. Persepolis changes that.

6. Joe Sacco, “The Fixer and Other Stories”

“The Fixer” is a war story set in peacetime. In 2001, Joe Sacco traveled to Sarajevo, hoping to find the interpreter who'd helped him during the Yugoslav Wars. By this time, correspondents had cleared out and soldiers had become civilians. Memories of atrocity were starting to slip beneath the surface — but Sacco's book excavates them.

During one flashback, Sacco portrays his wartime arrival to Sarajevo, and it's styled like film noir: hulking architecture, empty streets, long shadows. In a surreal scene at the Holiday Inn, the concierge points to the hotel on a city map.

“This is the front line,” she says. “Don't ever walk here.”

Then, in the lobby, Sacco meets his fixer.

7. Henrik Rehr, “Terrorist: Gavrilo Princip, the Assassin Who Ignited World War I”

Rehr's graphic novel paints a sympathetic portrait of a terrorist — which, in our day and age, makes it both provocative and timely. Rehr, a Danish artist now based in New York, is no stranger to modern terrorism: During the September 11 attacks, his apartment was less than two blocks from the World Trade Center towers.

But in “Terrorist,” Rehr takes his readers a century back in time, starting with a quote from Otto von Bismarck: “Europe today is a powder keg.”

In dark, atmospheric sketches, Rehr depicts the explosive start to World War I — the assassination of Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. He tries to explain why Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb, embraced anarchy in the fight against the Ottoman Turks and the Austro-Hungarian monarchy.

By focusing on Princip, Rehr examines what we'd today call radicalization — and for the most part, he succeeds in helping humanize an assassin. As Rehr writes in the afterword: “Empathy for both the murderer and his victim came easily to me.”

8. John Lewis, Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell, “March”

Growing up, Lewis encounters persecution everywhere. During a road trip to Ohio, he and his uncle have to carefully avoid segregated restaurants; after he goes to college in Nashville, student groups demand to be served at whites-only lunch counters. The book depicts the brutality, prison time and legal battles endured by Lewis and his fellow marchers, long before he became Congressman John Lewis of Georgia.

This year, “March” won three Eisner Awards, which are often called the Oscars of the comic books world. In the era of Black Lives Matter — and the year that Lewis led a congressional sit-in to demand gun control legislation — it's a timely and powerful book.

Two subsequent volumes also have become best-sellers.

9. Ulli Lust, “Today is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life”

Many scenes take place in bars or brothels and delve into a gritty leftist subculture.

“Today is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life” is a testament not only to how boldly Lust traveled, but also how far she's come as an artist. Soon after the road trip in her book, Lust became a single mother; she tried to make a living by publishing books she wrote for her son.

Only after three children's books did she start studying illustration in Berlin.

A shortened version of this list originally appeared on Longreads. Do you have a favorite on this list, or want to tell us about a book you think belongs here? Let us know in the comments section.