CIA urgently needs to increase its diversity, but that’s harder than it sounds

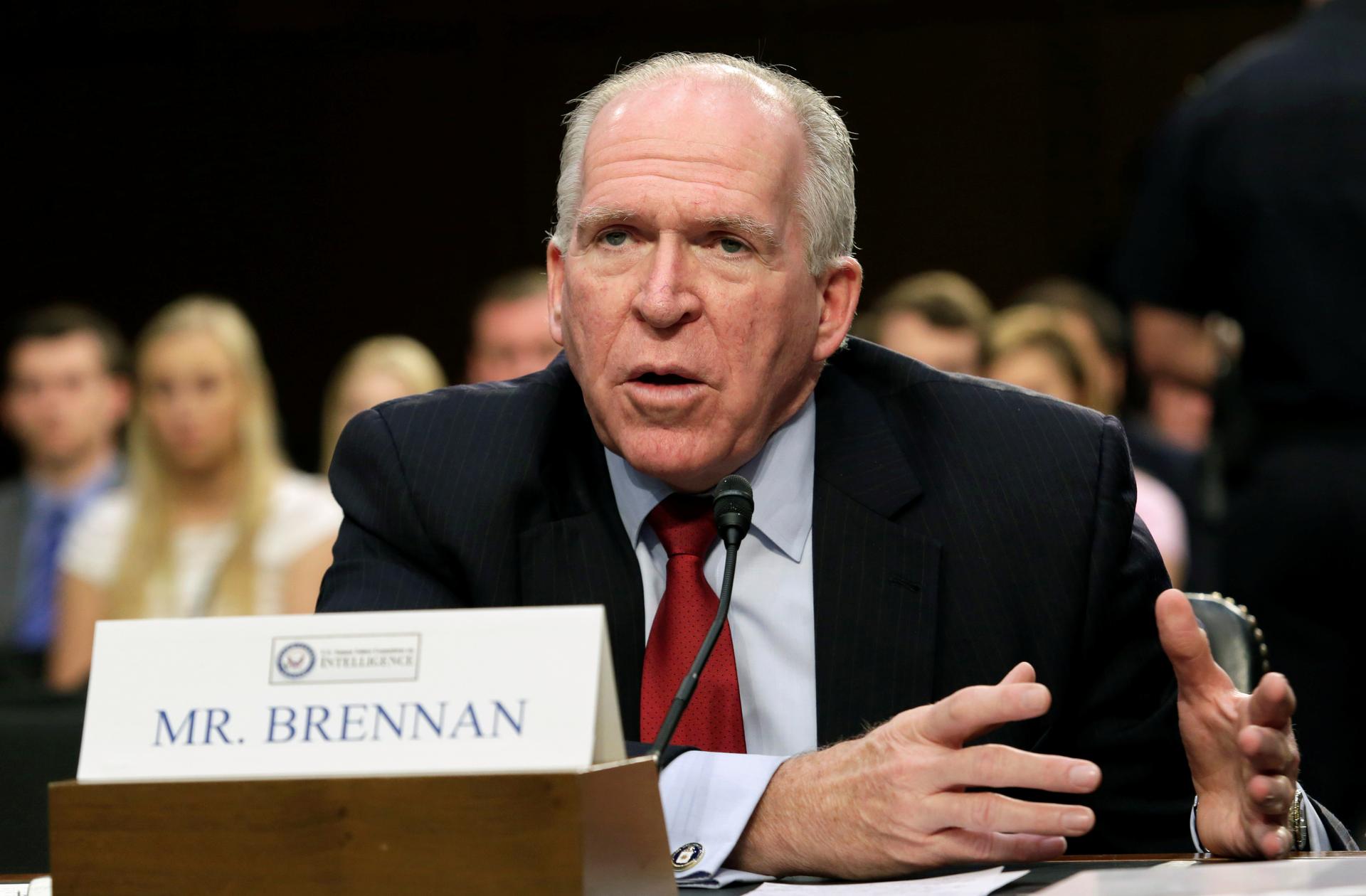

CIA Director John Brennan testifies before the Senate Intelligence Committee hearing on "diverse mission requirements in support of our National Security", in Washington, U.S., June 16, 2016.

Adrianne Rockhill is just the kind of person the CIA is looking to hire. She has degrees from several top tier universities, did private sector work that took her throughout the Middle East and Africa, and at a time when the agency is pushing to increase the diversity within its ranks, she’s African American.

The agency’s effort to improve diversity is about results, as CIA chief John Brennan explained to the Senate Select Intelligence Committee in June.

“Diversity not only gives us the cultural understanding we need to operate in any corner of the globe, it also helps us to avoid groupthink, ensuring we bring to bear, a range of perspectives on the complex challenges that are inherent to intelligence work,” he said.

Rockhill grew up in the Maryland suburbs, but now lives near London. She applied to the CIA but didn’t hear back for seven months, when she got a phone call.

“I picked up the phone and she said who she was, and I actually said, oh, I applied for that job months ago, and her reaction back was ‘We’re the CIA and we’re very busy,’ and I was like ok, ‘Fair enough!”

She grew up surrounded by friends and family who work for the federal government, and her father urged her to take the job, but Rockhill had several factors to consider. Taking a CIA job would mean a pay cut, and it could take a year to complete the hiring process.

For others, who are naturalized citizens, that process can be much longer, even though they are more likely to have the native language skills and cultural background the CIA needs in its efforts to fight terrorism

For her part, Rockhill ultimately decided to stay in the private sector.

“In a lot of ways this generation has been disillusioned. Coming from an HR background, you have to find something else to entice people,” she says.

That’s become especially true in today’s tight labor market, where organizations public and private all hire from the same limited pool of talent. For instance, whether it’s to fight terrorism or protect data privacy, virtually everyone needs to hire for cyber security.

And while companies like Google pay more, they too have well-documented diversity problems that are proving hard to fix.

Democratic Congressman Andre Carson is a member of the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. He’s also one of only two Muslims in Congress. He says diversity is critical, and that the government needs to work on hiring more Latinos, African Americans and Muslims in intelligence roles.

“I think when you have a diverse intelligence community that is reflective of larger society it makes for better intel, it makes for understanding cultural nuances,” he says.

The CIA does not track the religion of its employees, which isn’t unusual for the US government, but it’s safe to say that only a very tiny fraction of its workforce is Muslim.

One way to find a broader pool of talent is through outsourcing, but not all government work can legally be done by others. Earlier this year, Vice News published a report from the CIA’s Office of Inspector General that found contractors doing jobs that, by law, must be done by staff.

CIA contractors have been tasked with running some of the agency’s most controversial programs, including what the Bush administration called “enhanced interrogations.”

“They’ve hired hundreds of former agents and former officers in places like Guantanamo, and they hired a contract psychologist to run the torture program they did in Guantanamo and other places, and the secret prisons,” says Tim Shorrock, author of the book "Spies for Hire: The Secret World of Intelligence Outsourcing."

Recommendations for fixing the problem of contractors working outside their legal limit are redacted from that CIA report, but whatever they were, a spokesperson told Vice they were all were implemented.

Meanwhile, when terrorism strikes closer to home, as it did with June’s mass shooting at a gay nightclub in Orlando, that seems to spur people to apply for CIA jobs.

“We do see huge jumps in people who want to work for us depending on world events. Certainly, that generates a huge response from the American public as well as non-American citizens who want to come work for us to help protect the United States,” says Ron Patrick, the CIA’s s deputy director of talent development.

As for recruiting, Patrick says the CIA is unique in that they don’t participate in most typical forums, like social media or job boards. People tend to come to the CIA through school contacts, professional organizations, community organizations or, mostly commonly, through the CIA’s website, according to Patrick.

And sometimes, the agency even takes a shot at making a cold pitch to someone.

“There were several speakers at the conference and one of them had the exact skill set that we’re looking for for a hard-to-fill occupation, so following the presentation we took a break. I walked up to the person and just started talking and said, ‘Hey, have you ever thought of working for us.’”

This segment was part of America Abroad's episode "Espionage in the Age of Terror" about the current state of human intelligence gathering and its future. America Abroad is an award-winning documentary radio program that takes an in-depth look at one critical issue in international affairs and US foreign policy every month. You can follow us on Facebook, talk to us on Twitter, and subscribe to our weekly newsletter for updates.

Adrianne Rockhill is just the kind of person the CIA is looking to hire. She has degrees from several top tier universities, did private sector work that took her throughout the Middle East and Africa, and at a time when the agency is pushing to increase the diversity within its ranks, she’s African American.

The agency’s effort to improve diversity is about results, as CIA chief John Brennan explained to the Senate Select Intelligence Committee in June.

“Diversity not only gives us the cultural understanding we need to operate in any corner of the globe, it also helps us to avoid groupthink, ensuring we bring to bear, a range of perspectives on the complex challenges that are inherent to intelligence work,” he said.

Rockhill grew up in the Maryland suburbs, but now lives near London. She applied to the CIA but didn’t hear back for seven months, when she got a phone call.

“I picked up the phone and she said who she was, and I actually said, oh, I applied for that job months ago, and her reaction back was ‘We’re the CIA and we’re very busy,’ and I was like ok, ‘Fair enough!”

She grew up surrounded by friends and family who work for the federal government, and her father urged her to take the job, but Rockhill had several factors to consider. Taking a CIA job would mean a pay cut, and it could take a year to complete the hiring process.

For others, who are naturalized citizens, that process can be much longer, even though they are more likely to have the native language skills and cultural background the CIA needs in its efforts to fight terrorism

For her part, Rockhill ultimately decided to stay in the private sector.

“In a lot of ways this generation has been disillusioned. Coming from an HR background, you have to find something else to entice people,” she says.

That’s become especially true in today’s tight labor market, where organizations public and private all hire from the same limited pool of talent. For instance, whether it’s to fight terrorism or protect data privacy, virtually everyone needs to hire for cyber security.

And while companies like Google pay more, they too have well-documented diversity problems that are proving hard to fix.

Democratic Congressman Andre Carson is a member of the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. He’s also one of only two Muslims in Congress. He says diversity is critical, and that the government needs to work on hiring more Latinos, African Americans and Muslims in intelligence roles.

“I think when you have a diverse intelligence community that is reflective of larger society it makes for better intel, it makes for understanding cultural nuances,” he says.

The CIA does not track the religion of its employees, which isn’t unusual for the US government, but it’s safe to say that only a very tiny fraction of its workforce is Muslim.

One way to find a broader pool of talent is through outsourcing, but not all government work can legally be done by others. Earlier this year, Vice News published a report from the CIA’s Office of Inspector General that found contractors doing jobs that, by law, must be done by staff.

CIA contractors have been tasked with running some of the agency’s most controversial programs, including what the Bush administration called “enhanced interrogations.”

“They’ve hired hundreds of former agents and former officers in places like Guantanamo, and they hired a contract psychologist to run the torture program they did in Guantanamo and other places, and the secret prisons,” says Tim Shorrock, author of the book "Spies for Hire: The Secret World of Intelligence Outsourcing."

Recommendations for fixing the problem of contractors working outside their legal limit are redacted from that CIA report, but whatever they were, a spokesperson told Vice they were all were implemented.

Meanwhile, when terrorism strikes closer to home, as it did with June’s mass shooting at a gay nightclub in Orlando, that seems to spur people to apply for CIA jobs.

“We do see huge jumps in people who want to work for us depending on world events. Certainly, that generates a huge response from the American public as well as non-American citizens who want to come work for us to help protect the United States,” says Ron Patrick, the CIA’s s deputy director of talent development.

As for recruiting, Patrick says the CIA is unique in that they don’t participate in most typical forums, like social media or job boards. People tend to come to the CIA through school contacts, professional organizations, community organizations or, mostly commonly, through the CIA’s website, according to Patrick.

And sometimes, the agency even takes a shot at making a cold pitch to someone.

“There were several speakers at the conference and one of them had the exact skill set that we’re looking for for a hard-to-fill occupation, so following the presentation we took a break. I walked up to the person and just started talking and said, ‘Hey, have you ever thought of working for us.’”

This segment was part of America Abroad's episode "Espionage in the Age of Terror" about the current state of human intelligence gathering and its future. America Abroad is an award-winning documentary radio program that takes an in-depth look at one critical issue in international affairs and US foreign policy every month. You can follow us on Facebook, talk to us on Twitter, and subscribe to our weekly newsletter for updates.