From Swaziland to Papua to Georgia, here are the world’s forgotten revolutions

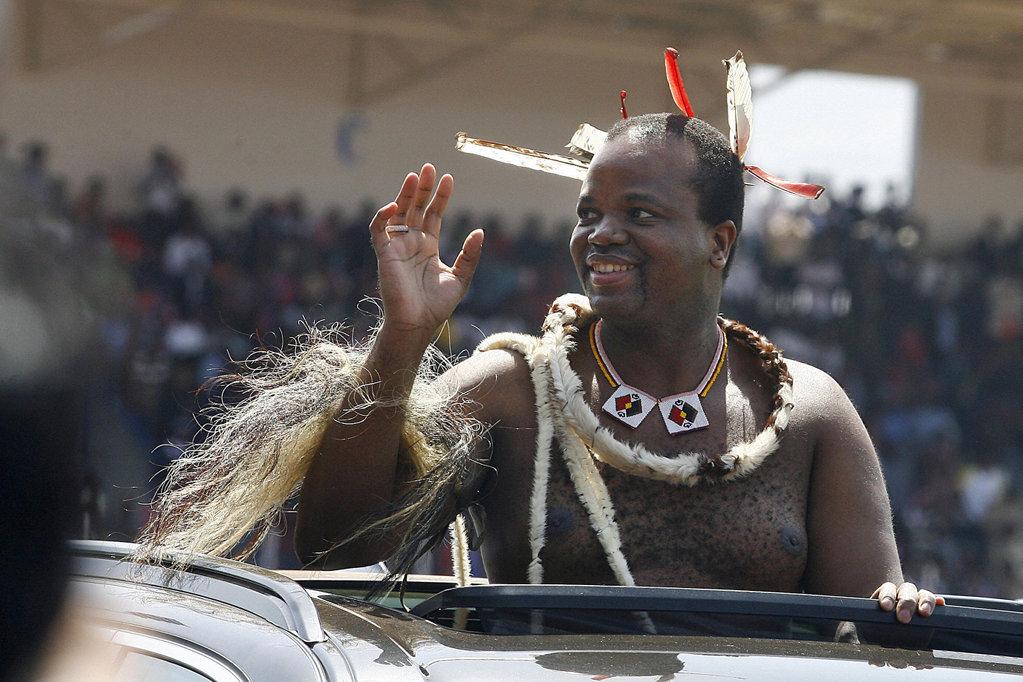

Swaziland, with a stagnant economy, rampant poverty and a soaring HIV rate, has caught the Jasmine contagion. King Mswati III, pictured here in 2008, is one of the world’s richest royals. Despite the unrest, he isn’t expected to go the way of Mubarak or Ben Ali.

Editor's note: The idea for this article was suggested by a GlobalPost member. What do you think we should cover? Become a member today to suggest and vote on story ideas.

LONDON, U.K. — As the Arab Spring moves into summer, uprisings are continuing to redefine North Africa and the Middle East. And with eyes focused on Libya, Syria, Yemen, Egypt, Tunisia and Bahrain, other lesser-known revolts are in danger of being lost in their shadow.

Despite brutal government retaliation in some countries, the Mideast’s pro-democracy movement has been so swift, tumultuous and unpredictable as to capture the media’s imagination, garnering a giddy, internet-age narrative about people power triumphing over oppression.

But away from dramatic TV coverage of war in Libya, away from the YouTube videos showing firefights in Syria, a myriad of forgotten, under-covered uprisings paint a different, less hopeful picture of popular struggle.

Some are smoldering civil wars. Others are protests that, year-after-year, fail to reach the critical mass, instead triggering violent backlash that typically generates outrage abroad but little else.

A sift beneath the main headlines uncovers political rumblings stretching from Europe's fringes to Southeast Asia's mountainous jungles — places that perhaps lack the strategic significance of Arab flashpoints yet are no strangers to calls for change.

Asked by GlobalPost to compile a list of lesser-known revolts that it is concerned about, Amnesty International nominated half a dozen struggles that, despite sparking scenes reminiscent of those witnessed in the Arab Spring, considerably fewer people will be aware of.

Other groups such as Human Rights Watch have their own lists. Georgia crops up because of recent political violence. But some struggles — such as a recent post-election flare-up in Albania — barely get a mention anywhere.

It isn’t immediately clear why certain uprisings capture the global imagination even as others are left to run their course in obscurity. A glance at the Amnesty chart suggests that a tricky political terrain and an obscure culture or cast of characters result in fewer headlines.

Chechnya, first on the list, is a textbook case. Both sides in this long-running conflict are seemingly guilty of violent excesses, albeit to differing degrees. Russia has fought two bloody wars with Chechen separatists beginning in the mid-1990s, ending its "counterterrorism" operations in 2009. But it still faces a sporadically violent Islamist insurgency with rights groups accusing authorities of serious abuses.

China’s treatment of ethnic Tibetans — familiar through the West’s affinity for the Himalayas, Buddhism and the charismatic Dalai Lama — receives considerable coverage. But Amnesty notes a forgotten conflict elsewhere within China’s borders. This involves the Uighurs, in the far west, who have been subjected to crackdowns since a major protest in 2009; China blames "mobsters" for fomenting Uighur uprisings against dominant ethnic Han Chinese. Another undercovered revolt is in Inner Mongolia. Beijing is currently stepping up action nationwide against dissent that it fears may develop into a "Jasmine revolution" echoing the Arab Spring.

Other Amnesty examples include Papua, one of several provinces where Indonesian authorities have sought to suppress separatist uprisings; Burma (also known as Myanmar), where the military regime has been waging war on ethnic groups including the Karen; Uganda, beset by political violence; and Swaziland, where calls for democratization are growing.

Misagh Parsa, professor of sociology at Dartmouth College, said these lesser-known struggles often grind on in vain because they lack the perfect storm of factors seen in the Arab uprisings — a merging of concerns over money, democracy, disenfranchisement, equality, class and civil liberties.

"All of these things combine and you bring in the internet, cell phones and all of this new technology, and because you add the working class conflicts and combine them, you get a lot of conflicts and that makes them very explosive," he told GlobalPost.

"These crises touch a lot of people, and when they touch a lot of people they can consolidate and come out and that becomes very impressive to the media and the world."

T. Kumar, Amnesty's advocacy director for Asia and Pacific, agrees. He said that because many of the unreported uprisings center on the problems faced by easily-suppressed ethnic minorities, popular support is likely to remain elusive.

"What is happening in the Middle East and North Africa is directly connected to national grievances where an overwhelming majority is fighting for human rights and democracy. When it comes to these smaller situations, they are overwhelmingly ethnic conflicts. These people are not the majority, so governments can easily control them — even a democratically elected government, which can often win votes by crushing minorities."

That said, change sweeping the Arab world has helped kindle new flames under a long-running insurrection in at least one country that until now has lacked the confluence of anger described by Parsa.

Dimpho Motsamai, an analyst at the South Africa-based Institute for Security Studies, told GlobalPost that while opposition to Swaziland's government was fragmented and somewhat unrepresentative of the wider population, recent events in the Arab world had spurred it to action.

And despite a dormant political scene and a crackdown on political dissent that, in addition to alarming Amnesty, has left many fearful of aligning themselves with protest movements, opposition does appear to be growing.

But, she said, whereas people in the Arab world have risen up against autocratic leaders seen as disconnected and contemptuous of their people, Swazis' respect for sub-Saharan Africa's last absolute monarch, King Mswati III, may spare him the same fate as Egypt's Hosni Mubarak or Tunisia's Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.

"There has been a sense of shared solidarity with the monarchy on the basis of culture and similarity," she said. "There is opposition to the way the current regime is governing the country, but not for the monarchy, and that makes the situation very difficult."