Germany embarks on a green energy revolution

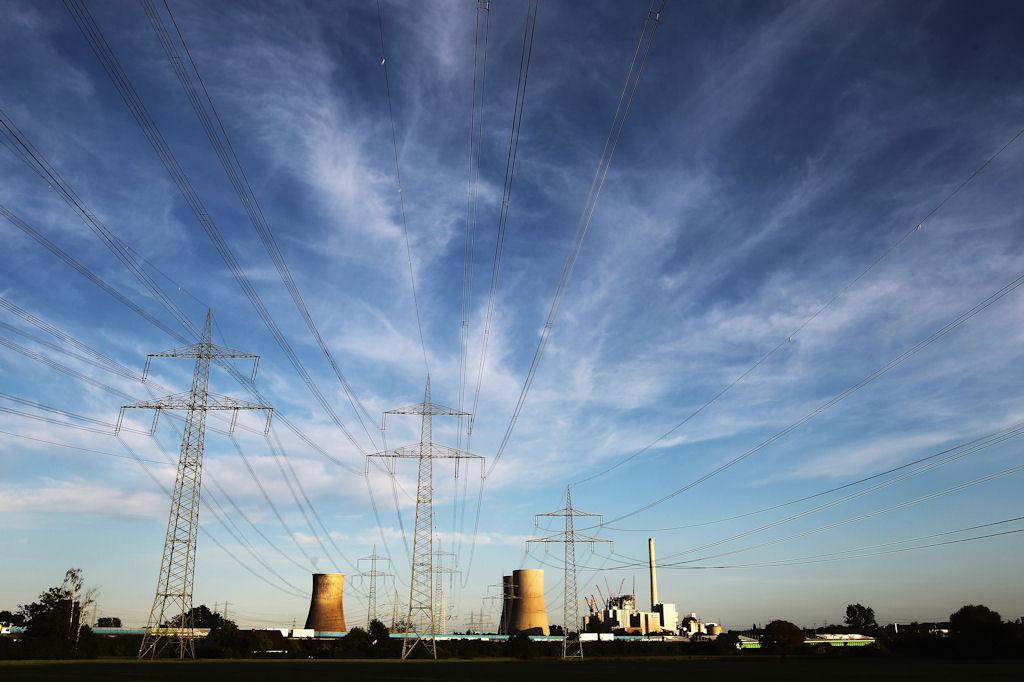

The Kraftwerk Westfallen coal-burning power plant stands illuminated on May 23, 2011 in Hamm, Germany.

BERLIN, Germany — As a trained physicist, Angela Merkel knows the calculated risks of nuclear power better than most politicians.

To the physicist, Germany’s 17 atomic reactors are no more dangerous after Japan’s Fukushima nuclear disaster than they were before.

To the politician, the risk assessment has changed dramatically. And on Monday in Berlin, the chancellor bowed to the majority of German people who want to see a quick end to nuclear power, putting in place a plan to shut Germany's plants by 2022.

That would make Germany the first industrialized nation since Italy in 1986 to shut down its nuclear reactors. The 17 reactors have contributed heavily to the European giant's energy needs and helped power its manufacturing-driven economy.

Germany hopes to largely replace the lost nuclear energy with renewables such as wind and solar, although some natural gas will also be needed to replace the energy that comes from nuclear reactors — almost a quarter of its total.

It will be a vital test case for a world fumbling to find the way toward cleaner energy, experts say. Germany already has a thriving green technology sector and a strong economy. It has a political consensus to move toward clean energy — though the pace of the transition has been hotly debated. Moreover, the public broadly supports clean energy and has long been suspicious of nuclear power.

If Germany of all countries can’t make this work, it will send a bad signal to the rest of the world, said Marcel Vietor, energy and climate expert at the Germany Council on Foreign Relations.

“We have the historic chance to set an example that this transition is possible and how it can be done,” Vietor said. “Will we make it in a way that preserves our competitiveness, in a way that will not harm our economic growth? That is extremely important for emerging economies like China and India who simply wouldn’t think of doing it in a way that harms their growth.

“If we don’t succeed, why should anybody else embark on this path? If we fail, the harm will be great on a global level.”

Few in Germany deny it is a gamble. Merkel admitted the transition, which constitutes a U-turn on her policy of last year to extend the lifetimes of the 17 reactors by an average of 12 years, would present a “great challenge.”

At present, Germany gets about 23 percent of its electricity from nuclear plants, compared with about 17 percent from renewable energy, nearly half from coal and about 13 percent from natural gas.

The aim is now to boost renewables to 35 percent of the energy mix by 2020 and to use more natural gas as a bridge until renewables can make up the shortfall left by the nuclear shutdown.

On Monday, Merkel touted the plan as an energy revolution. It was a “huge opportunity” for future generations and would put Germany in an international leadership role, she said.

On the whole, Germany appears upbeat about its prospects of managing the transition over the next decade. While it is a U-turn for Merkel, it is effectively a return to the nuclear phase-out timetable her predecessor, the center-left Gerhard Schroeder, established in 2000.

“I regard the plans as realistic and achievable,” said Claudia Kemfert, head of the energy, transportation and environment department at the German Institute for Economic Research. “In principle we are back to [Schroeder's] exit decision, which many firms had signed up to."

But if it is to work, experts say, Germany urgently needs an infrastructure overhaul, for instance expanding the electric grid and making it a so-called “smart grid” that responds to changes in supply and demand. Also, political leaders need to start preparing for the NIMBY (or “not in my backyard”) backlash once wind farms and new power lines begin to crowd the horizon.

The opposing, and indeed unavoidable, argument is that the cost of electricity will rise. Even the government itself admits there will be modest price increases as new infrastructure and some new gas power plants need to be paid for.

The big question is what effect this will have on Germany’s energy-hungry economy, which relies heavily on the big factories that assemble the country’s signature products such as cars and machinery.

The government is offering a 500 million euro ($714 million) compensation package for energy-intensive industries to help them with rising power bills — a figure slammed as too modest by some members of the pro-business Free Democrats, the junior members of Merkel’s ruling coalition.

Industry, which wanted much more time and flexibility for the transition, is appalled by the rigid deadline of 2022. Hans-Peter Keitel, president of the Federation of German Industries, said the government has rushed the whole process out of political expediency, risking Germany’s energy supply, its carbon reduction goals, its economic growth and its jobs.

“I am increasingly concerned by the clearly visible political motive in fixing a final and irreversible end point for the use of atomic energy with a haste that is unparalleled,” he said. “Reaching climate protection goals will now be more difficult and expensive as the shortfall in low-carbon nuclear power is met by additional coal and gas power.”

It is certainly a dim week for the big four utilities firms that currently earn up to 1 million euros ($1.4 million) a day from each reactor. They are now considering legal action against the government.

But advocates of the transition point to the brighter side: that this is a great chance for Germany. According to this argument, clean energy is the future and an economy that gets on board early — even if it causes a bit of pain in the short-term — will be better off.

“The economic opportunities are greater than the risks, because investment will be made in the three-figure billions in the next decade, which in turn will create value and jobs in Germany,” Kemfert said.

Vietor agreed, saying: “The German economy has to adjust to the new situation but it’s not something to fear. It might be new companies that succeed or old ones that transform themselves, but in the long run, it will be a good decision for our industry."

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!