Spanish mobs block evictions

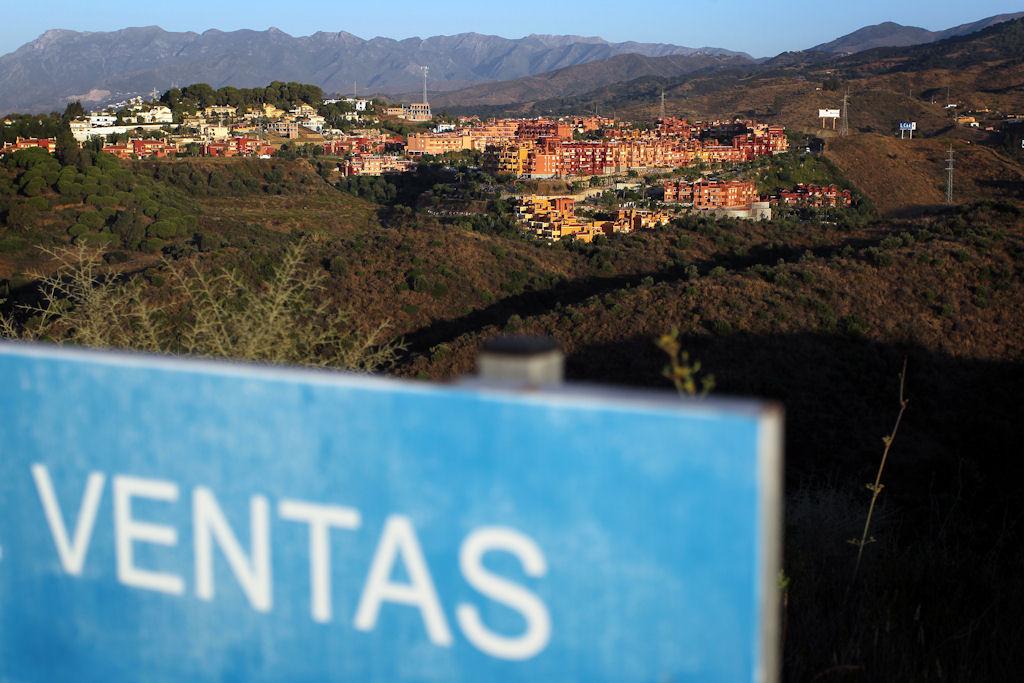

Early morning sun lights apartments and houses constructed during the Costa del Sol real estate boom, on Sept. 29, 2010 in Marbella, Spain.

MADRID, Spain — When Ronald de la Cruz bought an apartment in Madrid in 2004 for 216,000 euros ($313,000), it seemed like a good investment. The future looked bright for the 40-year-old father of four from the Dominican Republic who had been drawn to Spain by the wealth of jobs in the booming construction sector.

Seven years later, de la Cruz is unemployed, he can’t keep up with his mortgage payments and the bank is about to take his property back. To make matters worse, his apartment is now valued at just 108,000 euros ($156,000). That means he still has to keep paying the bank to make up for the difference between the market value of his apartment and his original mortgage.

“I feel like I’ve been defrauded,” he says. “The bank says my property has lost half its value.”

The Spanish economy’s difficulties, including a soaring unemployment rate, have led to a wave of similar cases, with home repossessions rising since the real estate market collapsed in 2008.

But in recent months, victims of the crisis have been striking back at lenders. They have started blocking the doors of properties due to be repossessed so that officials cannot deliver eviction orders. The “15-M” or May 15 civic movement, which staged sit-in protests in cities across Spain this spring, has thrown its weight behind the anti-eviction initiative.

“In this crisis, our government has bailed out banks that are not giving credit but at the same time are trying to evict people,” said Eduardo Munoz, a spokesman for the 15-M movement, which is made up mainly of young people. “People are really mad right now.”

The anti-eviction drive started in Barcelona and was led by Latin Americans, who were particularly exposed to the crisis since many worked in the construction sector. However, with many Spaniards now also in danger of losing their homes, several social organizations across the country have joined to give the movement greater heft.

Activists use social networking sites to announce imminent evictions, ensuring that hundreds of people turn up at the property in question, peacefully preventing court officials and police from enforcing the repossession.

On June 15, Luis Dominguez, a 74-year-old man in Parla, near Madrid, contacted the 15-M movement because his house was due to be repossessed the next day. When officials arrived to evict Dominguez, who has health problems and uses crutches, they could not reach his door because dozens of protesters were blocking it.

Those involved say they have stopped about 40 evictions over recent months, although they estimate that more than 200 are taking place each day across Spain.

“People can’t pay back their loans and mortgages and so the banks have to show their muscle — they don’t want to allow irregularities,” said David Carominas, a Madrid-based real estate analyst. “We’re all trapped in this real estate bubble, because we bought the idea that it’s better to own than to rent. As it was so easy to get money, we went after the easy money — but it’s difficult to pay that kind of money back.”

The burst property bubble has left more than 700,000 unsold new homes and a market whose prices are close to freefall. In addition, Spain has a 21 percent jobless rate, the highest in the European Union.

The country is also struggling to match the growth rates of many of its neighbors. Despite a relatively low public debt, Spain's large deficit has fuelled doubts about its ability to finance payments and even made it a potential candidate to follow Greece, Ireland and Portugal in requiring an emergency bailout — although the government insists that will not happen.

The Socialist administration of Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero has embarked on an unpopular reform program in a bid to ward off such bailout rumors, including cutting public sector wages, increasing VAT, freezing pensions and raising the retirement age from 65 to 67.

Those involved in the anti-eviction actions admit that the bank usually obtains a new court order to evict the homeowner within a few weeks. However, they want to see the law changed so that when the keys to a property are handed back, all pending debts are cleared. They also want banks to be more sympathetic to families who are in particularly desperate financial situations.

The pressure seems to have paid off, at least in part. On June 30, the Socialists reached an agreement with other political parties to ensure properties are given a higher, fairer market valuation when owners are unable to keep up payments. The parties also agreed that a higher portion of an owner’s income should be protected from the bank in case of non-payment of a mortgage.

“Even the politicians are realizing that it’s time things changed,” said Aida Quinatoa, who has been one of the leaders of the anti-eviction movement, on hearing of the slated reform. “The banks’ abuses have reached such a point that people won’t stand it any longer.”