Japan: Islands in dispute. Is K-pop too?

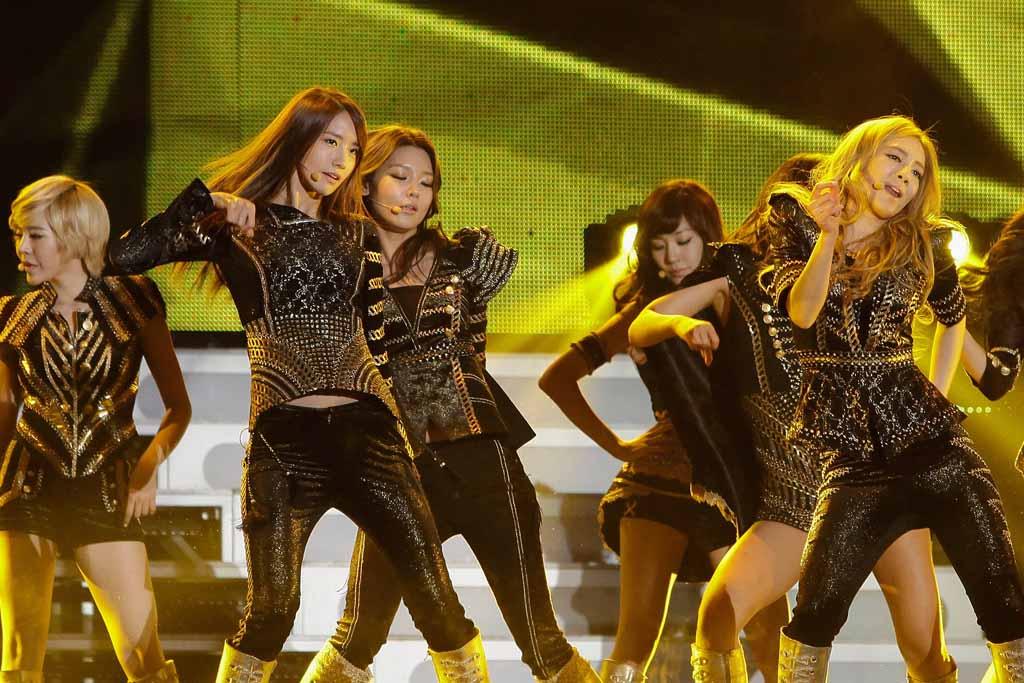

South Korean girl group Girls’ Generation perform at the 21st High1 Seoul Music Awards in Seoul on Jan. 19, 2012.

TOKYO, Japan — While Japan and South Korea try to steer a way out of their latest row over ownership of two rocky islands, animosity is creeping into the countries' close cultural ties.

Diplomatic relations have quickly deteriorated since South Korea's president, Lee Myung Bak, made a provocative visit to the Dokdo islands — known as Takeshima in Japan — in August.

The former enemies, now important trading partners with shared geopolitical interests, are behaving less like allies than a bickering couple, drawing on deep wells of resentment to make their point.

Japan has tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade its neighbor to hammer out their differences over Takeshima at the International Court of Justice. South Korea, meanwhile, took the unusual step of returning a letter of protest over Lee's visit from the Japanese prime minister, Yoshihiko Noda.

Japan is thought to be edging away from its threat to annul a currency swap agreement when it comes to an end in October, amid warnings that a currency crisis in South Korea could also harm its own economy.

South Korea, where ownership of the islands is closely linked to the recovery of its national dignity following Japan's defeat in the World War II, believes it has the upper hand in the dispute, and not without good reason.

The islands, which Seoul insists were ceded by Japan under the terms of the 1952 San Francisco Peace Treaty, are occupied by a South Korean police detachment and an elderly fisherman and his wife. As Oh Young Jin, managing editor of the Korea Times, said in a recent column: "If Dokdo is Japanese territory, why can't a Japanese prime minister … come and visit it?"

Japan's outrage intensified after Lee dragged emperor Akihito into the argument, challenging him to apologize for Japan's 1910-1945 occupation of the Korean peninsula or banish all thoughts of visiting South Korea.

And then, of course, there's K-pop.

While Japan struggles with its diplomatic response, popular resentment is spilling over into the Korean wave. The recent boom in global interest in South Korean pop culture has helped K-pop bands exploit Japan's huge music market — the world's second biggest after the US — while its dramas have become a wildly popular staple of Japanese TV output.

More from GlobalPost: K-pop born in Korea, headed for the USA

The tipping point was the participation of two South Korean celebrities in a swimming relay from the mainland to Takeshima on Aug. 15, the day Japan remembers its wartime defeat and Koreans celebrate liberation from their former oppressor.

In late August, Japan's senior vice foreign minister, Tsuyoshi Yamaguchi suggested that the TV actor Song Il Gook, would no longer be welcome after he took part in the swim, along with the pop singer Kim Jang Hoon and about 40 others. "I feel sorry for Song," Yamaguchi said in a TV interview. "It will not be easy for him to come back to Japan. That' the feeling among the public."

Song, who endeared Japanese audiences with his lead role in the TV drama Jumong a few years ago, retaliated on Twitter: "I am lost for words. Long live the Republic of Korea!" Japanese satellite broadcasters said they would postpone the screening of two dramas featuring Song.

Korean pop artists and their management agencies have gone to extraordinary lengths to cultivate the Japanese market. The K-pop genre has produced a steady stream of award-winning hits and fueled an assault on the Japanese pop charts that few Western artists have been able to match.

The boy band Toho Shinki began the charge several years ago, followed more recently by a string of girl bands, led by Girls' Generation, a nine-member group who completed a sellout tour of Japan last year.

More from GlobalPost: North Korea's answer to K-pop

According to the Korea Creative Content Agency, a body set up by the country's government to project its "soft power" abroad, South Korean exports of music and TV dramas to Japan — easily the biggest single overseas market with a 40 percent share — were worth $117 million in 2010. In 2011, the Korea wave added an estimated $3.8 billion of revenue to the South Korean economy.

Girl's Generation and the actor credited with starting the boom, Bae Yong Joon, now find themselves in an uncomfortable professional limbo: do they support their country's claims in public and risk alienating a core foreign audience, or remain quiet and leave themselves open to accusations of disloyalty?

It remains to be seen whether the Takeshima-Dokdo spat sees Japanese consumers fall in line behind their political leaders. Weaning themselves off K-pop and TV dramas will not be easy. In a recent poll conducted by the Japanese women's magazine Josei Seven, only 10 percent of respondents said the row over Takeshima had made them consider abandoning the Korean wave.

Any prolonged cultural estrangement would come at a cost to both economies: ordinary South Koreans and Japanese drawn to one another's food and culture form the bulk of the 5 million people who travel between the two countries every year. While Japanese authorities have not issued travel warnings, the country's embassy in Seoul has advised visitors to avoid anti-Japanese protests.

Korean cultural promotion officials in Tokyo were quick to distance themselves from the row, although one, who spoke to GlobalPost on condition of anonymity, admitted that some events in Japan had been affected.

"The political situation isn't good and that has led to the postponement of a few isolated events," the official said, adding that organizers had also received threats of disruption from Japanese ultra-nationalists.

Other events, however, have passed off without a hitch, including a meeting of fans of the Korean boy band Super Junior. "Japan has to remember that culture and politics must treated separately," the official said.

The biggest threat to cultural exchange may come from the South Korean government itself, which has spent huge sums promoting the country's pop artists throughout Asia. The Sports Chosun newspaper said it was "too early" to say if K-pop would stay above the fray, but warned, "If the government gets into this, there could be some problems for the K-pop industry."