A Daughter’s Journey, Part VII: Testing the fear of stigma

WASHINGTON, DC — How would I tell my grandma?

The question raced through my mind while I swept the plastic mouth swab between my gum and my upper lip. I was sitting in a testing van in Anacostia, and I had taken a break from my reporting to get an HIV test.

It would be the greatest tragedy, I always thought, if I were to die from the same disease as my mom. This fear is what kept me from wanting to know my own HIV status for 18 years.

At the 19th International AIDS Conference in Washington, DC, doctors, researchers and advocates stressed how far we have come in the past 30 years of fighting HIV. Speaker after speaker assured attendees that science can now help HIV-positive people live long, healthy lives.

The biggest threat to the goal of transforming HIV/AIDS from a death sentence to a manageable chronic disease, it seems, is getting people tested and aware of their status so they can take advantage of the treatments available.

Why is this such a challenge? Because of stigma.

“Stigma has been around since the beginning of the epidemic, but those reasons have changed now,” said Dr. Dianne Rausch, director of the National Institute of Mental Health Division on AIDS Research. “With universal testing, treatment, and linkage to care, stigma is a barrier for people being able to get engaged, and it’s becoming more obvious that it is a problem again.”

The topic of stigma may not be new, but it is surely being talked about in new ways. Phill Wilson, founder and executive director of the Black AIDS Institute, said that as a society we have spent a lot of time looking at stigma from a position of deficiency. People with HIV have historically felt that they could not get the support or healthcare they needed. In response, Wilson said, HIV-positive people adopted a notion of secrecy under the guise of privacy, for protection — a value we still hold on to today. Now stigma must be addressed as a hurdle to be cleared in order for people to become open about their status.

Stigma can be both real and perceived, Wilson added.

“There is a difference, sometimes without a distinction, between actual stigma and perceived stigma,” he said. “Actual stigma is, I disclose that I’m HIV positive, and I go to a restaurant and they don’t serve me. Perceived stigma is that I think that my classmates are going to tease me even though they have not actually teased me.”

But perceived stigma does not come from nowhere. It’s a comment on what we see happening in our society and in our life experiences—people being ostracized for their otherness.

| |

An HIV test in the Community Education Group (Tracy Jarrett/GlobalPost) |

For people living with HIV, there can also be multiple layers of stigma. Wilson said that HIV stigma can be a surrogate for how people are dealing with other things, such as their sexuality, addictions, or family issues. Stigma on top of other insecurities can end up confirming a person’s feeling that they are not worthy in society.

“Here is the dirty secret: everybody is afraid of being stigmatized because everybody has an ‘other,’” Wilson said. “All of our societies struggle with otherness. The more marginalized a people are, the less tolerant we are of their otherness.”

Having lost my mom to AIDS-related complications, I have become outspoken about issues concerning HIV. I do not hide my story, and I have no shame. My mom likely contracted the virus from a boyfriend who did not know he was infected, or did not disclose his status.

But I do wonder, if my mom had contracted HIV from IV drug use, or sex work, would I be as open about her story? Maybe I would be ashamed, or uncomfortable, and keep my mom a secret. Today I am none of those things.

Even still, waiting for the results of my HIV test, I wondered how I would react if I were positive. I was tested for HIV after my mom died when I was five years old, but I didn’t get tested again until I was 22. I was too scared.

Two years later, at age 24, while I was reporting on the importance of getting tested in Anacostia, I decided to get tested again. And even though I knew I had been safe, for the 20 minutes I waited for my test results, my world felt filled with uncertainty. Would I tell my family? Would I live in denial? How would I cope?

“We can’t wait for it to be safe to come out, to start to come out, because it is the coming out that will make it safe.” Wilson said.

Eliminating stigma is a process, and a critical part of that process is having the courage to know and be open about your status. This is a challenge my own family faced when coping with my mom's illness.

I know firsthand how scary going to be tested can be. The thought of testing positive and then having to tell my grandma that I share the same fate as her daughter is more unnerving still. I tested negative. But if I were to find out that I was infected, I know that saving my life is worth it.

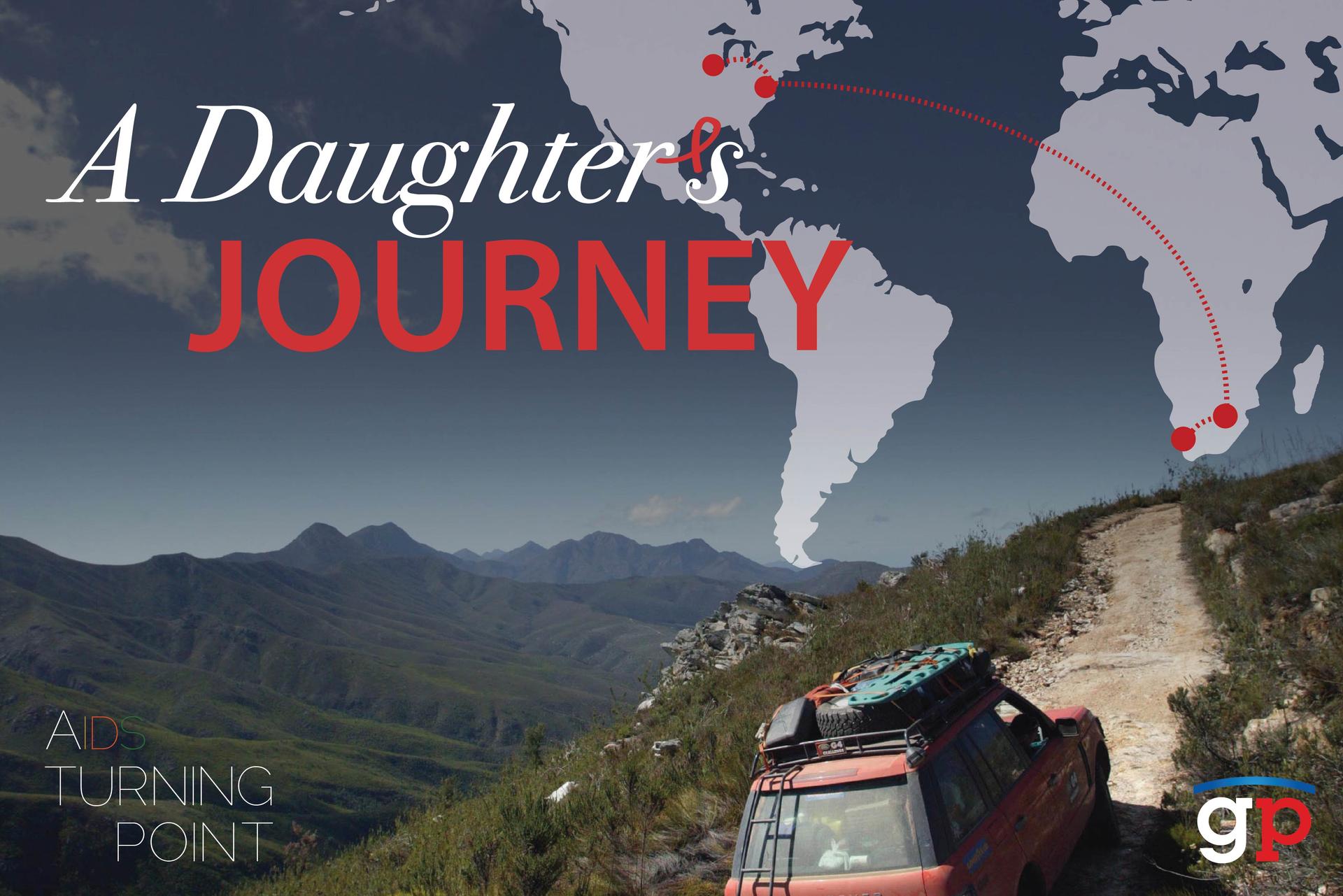

“A Daughter's Journey" is a series of blog posts by Tracy Jarrett, a GlobalPost/Kaiser Family Foundation global health reporting fellow. Tracy is traveling from her hometown, Chicago, to Cape Town, South Africa as part of a Special Report entitled "AIDS: A Turning Point.” Read Parts I, II, III, IV, V, and VI of Tracy's journey on GlobalPost.

More from GlobalPost: AIDS: The stories that change the game