A Daughter’s Journey, Part II: Notes from New York

NEW YORK — Cape Town is worlds away from Chicago, and before I head to South Africa I want to speak with the movers and shakers of HIV prevention and treatment in American cities — where HIV infection rates rival those in southern Africa — about what they think are the “needs improvement” areas for treating the virus in the US.

Dr. Victoria Sharp, who works in HIV clinical care and management at St. Luke’s hospital in Manhattan and who currently serves as president of the board of HealthRight International, told me that despite our success in treating and preventing HIV in the US, there is still much to learn.

“We have multiple tools in our toolkit,” she said, but she does not believe that we are using them to the best of our ability.

“We don’t always do a good job of linking people to treatment,” she explained. She gave an example of a woman who tested HIV positive and then was asked to wait five weeks for the next open appointment before beginning treatment.

“That is called a non-appointment,” she said. “It is so far in the future that people move on and forget to take action."

Life getting in the way of pursuing HIV treatment seems like it could be a big problem in South Africa as well, where stigma is high, access to clinics is often difficult and where the standard of living is drastically different.

I wonder if Johannesburg and Cape Town are better about providing immediate counseling and treatment for patients who test positive, since the HIV/AIDS rate is so much higher there.

In Harlem I also spoke to Susan Rodriguez and her daughter Christina Rodriguez. Both are HIV positive, and they started SMART University, and the SMART Youth program, organizations that teach healthy living to women and youth affected by HIV/AIDS. They founded SMART to fill their own needs for education and support, which were not available in their neighborhood.

![]()

Christina (photo left) is now 20 years old and by looking at her you would never think that she is sick. When we met at SMART she came to shake my hand shyly but professionally, then sat across from me at a gray classroom-style table.

I asked her what she wanted to get out of our interview, and she told me she thinks HIV infected youth are overlooked and that she wants people to recognize that there is a population born with HIV that had no choice in whether they contracted the virus or not.

She also told me that HIV positive youth don’t always have access to the one thing they want most: mentorship from others who were born with HIV. For her its important to find others with whom she can talk about starting families, having sexually active relationships, and dealing with the responsibility of taking care of yourself when your peers are partying in college. This is what SMART tries to provide, but many of these types of programs don’t survive, and funding is a problem for SMART every year as well.

Dr. Elaine Abrams is the resident Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) expert at ColumbiaUniversity’s Mailman School of Public Health. She told me that there are lessons to be learned from community programs in South Africa that try to address the economic challenges that come along with treating large HIV positive populations.

“Perhaps there is an opportunity here to limit costs by borrowing from decisions in southern Africa, where patient care decisions include economic analysis,” she said.

I also spoke with Thurma Goldman, who is the PMTCT lead at PEPFAR, after spending six years with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in South Africa. She agreed with Dr. Abrams, saying that volunteer work and mentorship from HIV positive patients for other HIV positive patients is a large component of HIV prevention and care in South Africa.

Sitting across from Christina, both of us with our brown, puffy curls combed over our left shoulders as if mirroring one another, I couldn’t help but think about our similarities. We are both in our early twenties, born to mothers who were unaware of their HIV positive status when we were conceived, and we both had the same chance of being infected.

But there we were, her with HIV and me without.

Despite both being half orphaned by the disease (she lost her father when she was five—the same age I was when I lost my mom) both of our families had told us to keep our relationship with the virus secret until we were older. I wondered who I would talk to about sex and relationships if I were positive, and if I would feel like I had friends to turn to who also had the virus.

So this is the question I would like to follow as I begin my journey in South Africa: Is there more community involvement and mentorship for HIV patients, by HIV patients, in South Africa than there is here? Can we learn from these programs, and could they help support people like Christina in East Harlem?

My first stop in Johannesburg will be a USAID-funded Perinatal HIV Research Unit at a hospital in Soweto township. I will begin looking into how South Africans are able to treat and support mothers and babies who are HIV positive. Check back in to see what I find.

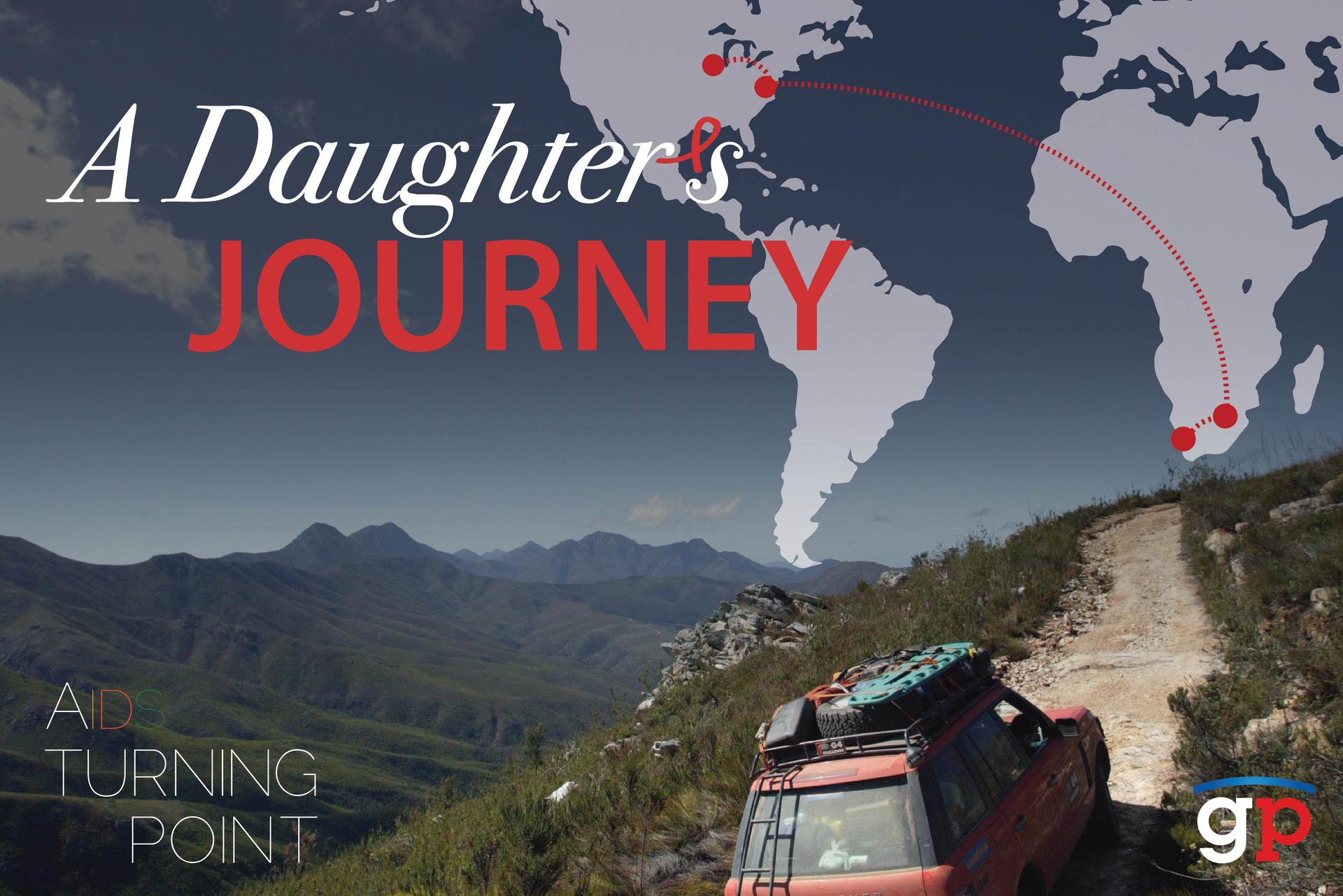

“A Daughter's Journey" is a series of blog posts by Tracy Jarrett, a GlobalPost/Kaiser Family Foundation global health reporting fellow. Tracy is traveling from her hometown, Chicago, to Cape Town, South Africa as part of a Special Report entitled "AIDS: A Turning Point.” Read Part I of Tracy's journey here.