NASA Mars rover finds clear evidence for ancient, long-lived lakes

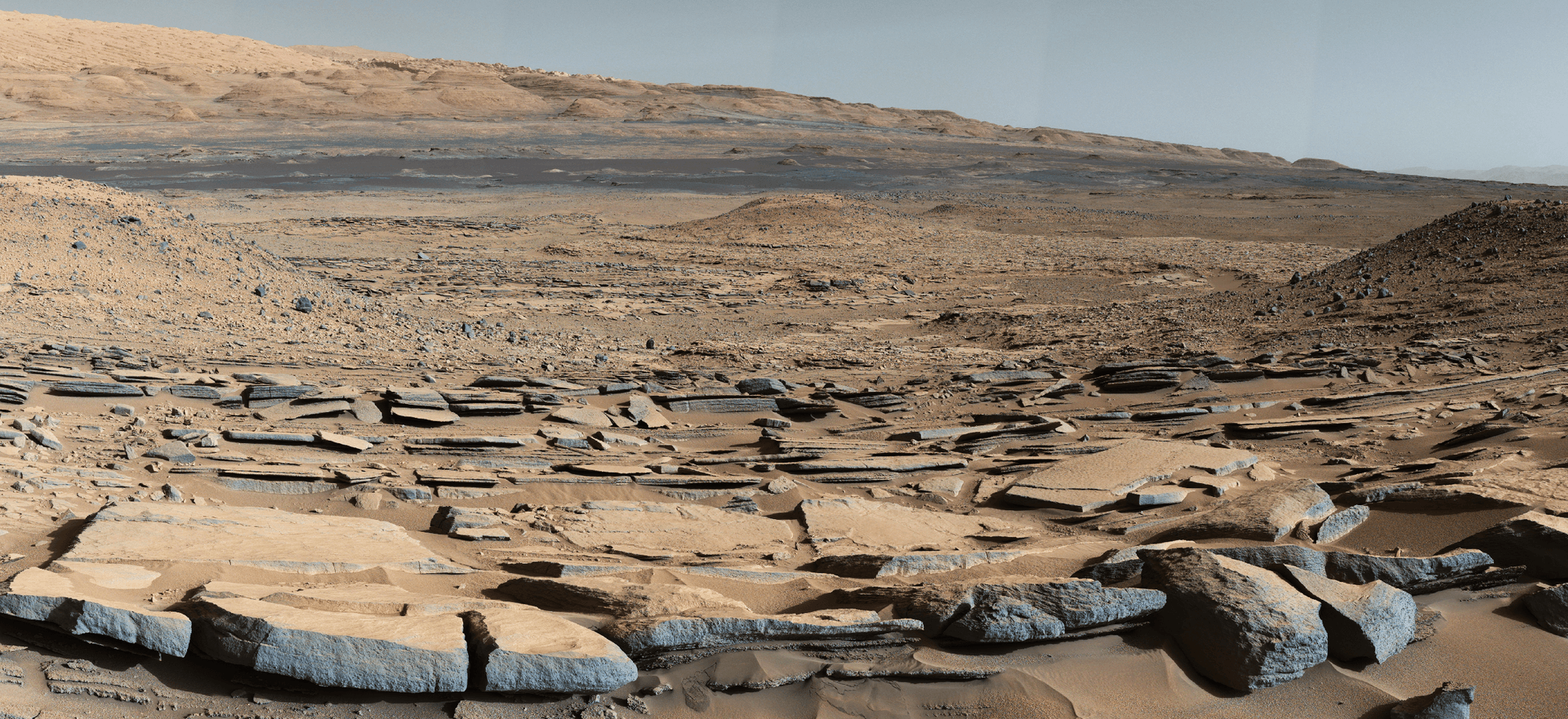

A view from the "Kimberley" formation on Mars taken by NASA's Curiosity rover.

By Irene Klotz

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — Three years after landing in a giant Martian crater, NASA's Curiosity rover has found what scientists call proof that the basin had repeatedly filled with water, bolstering chances for life on Mars, a study published on Thursday showed.

The research offered the most comprehensive picture of how Gale Crater, an ancient, 87-mile (140-km) wide impact basin, formed and left a 3-mile (5-km) mound of sediment standing on the crater floor.

Early in its mission, Curiosity discovered the gravel remnants of streams and deposits from a shallow lake.

The new research, published in the journal Science, showed that the crater floor rose over time, the result of sediments in water settling down, layer after layer, for what may have been thousands of years, California Institute of Technology geologist John Grotzinger said.

"We knew that we had a lake there, but we hadn't grasped just how big it was," Grotzinger said.

Water from north of the crater regularly filled the basin, creating long-lasting lakes that could have been a haven for life. Scientists suspect the water came from rain or snow.

"If one discovers evidence of lakes, that's a very positive sign for life," Grotzinger said.

Eventually, the crater filled with sediments. Then the winds took over and eroded the lakebed, leaving behind just a mound at the center. That mound, named Mount Sharp, is why Curiosity was sent to Gale Crater to look for ancient habitats suitable for microbial life.

Scientists have learned that Mars had all the ingredients thought to be necessary for life.

Exactly how Mars managed to support long-lived surface water is a mystery. Billions of years ago, the planet lost its global magnetic field, which allowed solar and cosmic radiation to gradually blast away its protective atmosphere. Under those conditions, liquid water evaporates quickly.

"If you have a body of standing water that lasts more than hours to days without boiling off, that is a huge surprise," Grotzinger said.

Current computer models of Mars fall well short of an atmospheric blanket thick enough to support the long-lived lakes, the researchers noted.

Grotzinger suspects that Mars may have had greenhouse gases or some other chemistry that so far has gone undetected.

Last week, another team of scientists published research showing that trickles of briny water seasonally flow on present-day Mars, carving narrow streaks into cliff walls throughout the equator. The source of the water is not yet known.

(Reporting by Irene Klotz; Editing by Scott Malone and Will Dunham)