In Kenya, sex workers want jobs and protection, but not just condoms

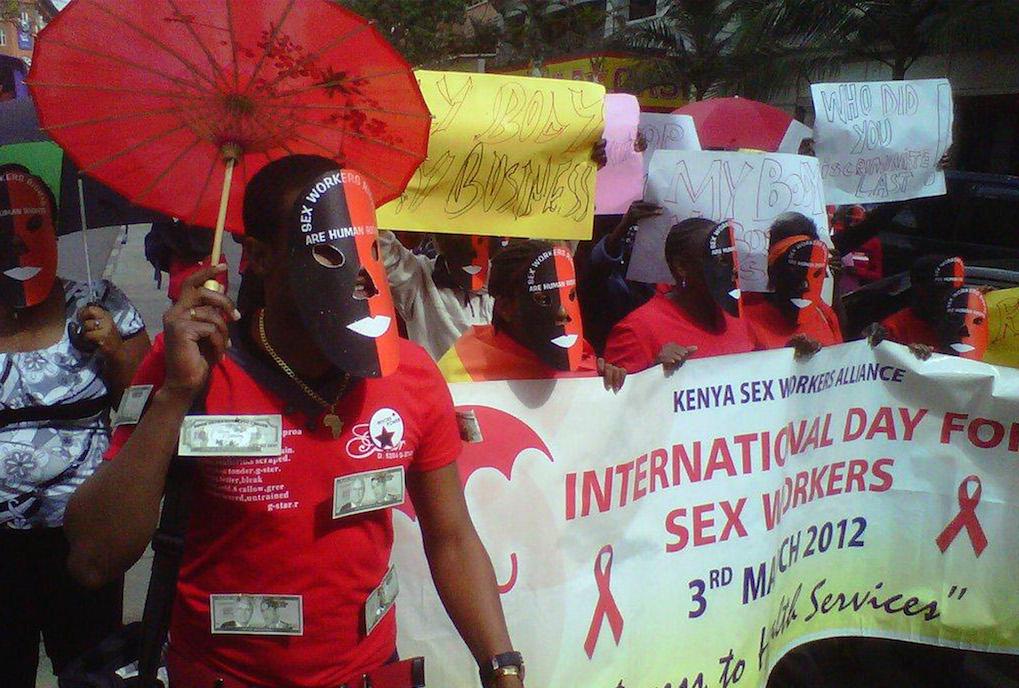

Kenyan sex workers march to protest for the legalization of prostitution on March 6, 2012 in Nairobi. Under red umbrellas and in red T-shirts, the protesters bore masks written with the phrases: “sex workers rights are human rights” and “my body, my business.”

Editor’s note: Elizabeth Daube traveled to Kenya last year as a master’s student at Boston University’s School of Public Health through the Pamoja Together reporting project—a collaboration of students around the world committed to “telling the stories of foreign aid.” Her graduate thesis looked at the tension between the pro-sex worker rights and anti-trafficking movements. This guest post has been adapted from “Selling Sex in Kisumu,” which originally appeared on the Pamoja website.

I started looking for sex workers long before I got to Kenya. I scoured Google, Facebook, Twitter—I even stumbled upon a message board made by foreign men looking for the “freshest” girls in the country.

After months of research on sex workers, violence and HIV around the world for my master’s thesis at Boston University, I’d heard what the public health and policy wonks had to say. Some portrayed sex workers as victims suffering unimaginable abuse; others depicted them as empowered entrepreneurs. I sensed the reality was somewhere in between. Talking to actual sex workers seemed like the only way to get closer to the truth.

With BU’s Pamoja Together reporting project, a storytelling collaboration of students in Boston and Kenya, I got my opportunity. In 2013, I was one of eight fellows selected to report in Kenya for Pamoja and work with 10 local students to share the stories of Kenyan recipients of foreign aid—capturing the perspectives of people on the ground, as opposed to those of outside experts. A few weeks and 7,000 miles later, the 18 of us were planning our reporting on global health and development issues over local Tusker beers.

Our Kenyan counterparts gave us the scoop on local culture and attitudes toward HIV, which has infected about 6 percent of adults. The disease has concentrated in the western Nyanza and Rift Valley regions, where more than half of all HIV-positive people in Kenya live, and we were near Kisumu, Nyanza’s largest city. Kisumu is a trading hub on Lake Victoria where men often travel for work—and where many of them buy sex from women working near hotel “hot spots.” A recent study found more than half of Kisumu’s female sex workers are HIV positive.

I wanted to meet these women, but my Kenyan colleagues didn’t exactly have them on speed dial. After many inquiries, I found KASH, or Keeping Alive Societies’ Hope—a Kisumu NGO funded by several US donors that helps sex workers protect themselves from HIV.

KASH advocates for sex workers’ rights, not just condoms.

The “hot spot”

When I first met Aluna at the KASH office, she was smiling and wearing a pink sweater and pressed slacks, carefully arranging the bangles at her wrists. She reminded me of a friendly suburban mom.

But Aluna was a sex worker, and a KASH peer educator. In her role, she brings together other sex workers for regular group meetings, where they discuss their problems and strategize ways to address them.

Aluna took me—along with Algah, my Pamoja peer and volunteer translator—to a “hot spot” where we could observe one of these meetings. We walked out of the midday sun and into a dark bar, then up the back stairs and down a hall of locked doors. At the end of the hall, two women in jeans and T-shirts were waiting in a small room, lounging on well-worn beds. Broken bed frames lay stacked in a nearby alcove. As more women filed in, they sat on the hallway floor and removed their shoes. When a pregnant woman arrived late, someone gave up a coveted plastic chair. In all, about 18 women showed up. Some yawned; Aluna told me most of them work from about 5 p.m. to 5 a.m.

Aluna and Algah explained my presence in the local dialect, Luo, and each woman introduced herself. Then Aluna asked the group if they’d faced any challenges since their last meeting. There was a sudden flurry of Luo, along with big swooping gestures and pointing fingers, peppered by English words: “uniform” and “Land Cruiser.” Algah told me they were complaining about police harassment.

Before we could ask more, the women suddenly turned to a recent episode of violence.

They started discussing a young woman who was sitting on the floor near my feet. She was wearing a flowery tank top over a black T-shirt, and she kept her eyes fixed on the floor. When she glanced up to address the group, her eye was so swollen that I almost winced. Shades of deep purple surfaced, despite the darkness of her skin.

“He refused to wear a condom,” she said of the client, almost whispering. “He started beating me and I fell down. He stepped on my head with two legs.” Someone explained to the group that other sex workers had heard her cries and entered the room; the man had fled, and her friends took her to the hospital.

A KASH field officer who was leading the meeting with Aluna assured the woman that “KASH will be there to defend you.” KASH has modest funding and a staff of only 12, but one lawyer and a few paralegals are among them, precisely for cases like this one. Because most sex workers don’t want to end up in court—cases can drag on for months or years—the legal team usually negotiates with police, and has found some success along the way.

KASH also trains police, trying to get them to see sex workers as people with human rights. But this strategy hasn’t yielded great results. “There is no trust,” one woman explained. “We know the policemen. They come as customers, ask for a price, then they start beating.”

The KASH officer offered some practical guidance: “When they pick you [up], call us and we will come.” Later, she snapped pictures of the victim’s swollen eye and the abrasions on her face and neck. KASH lawyers can use photos like these as evidence even after the victim’s wounds begin to heal.

Money talks

If violence is so routine, why do sex workers take the risk? I wasn’t exactly shocked by Aluna’s answer: “Money.” She needed it when she was 12 years old and a man propositioned her on a bus. And she still needed it when we met, so she could support her five kids.

Many researchers tend to skip over the details when it comes to how much money sex workers make—because they don’t view sex work as legitimate employment, or because they focus on health to the exclusion of economics. But regardless of one’s opinion of sex work, money undoubtedly motivates it.

And according to Aluna, it pays relatively well. She estimated that if she could get five clients a day at a high price—400 Kenyan shillings per transaction—she could make up to $23 USD a day, or about $8,000 a year. This amount wildly exceeds the incomes of many Kenyans, who, according to World Bank estimates, earn an average of just $820 a year.

But competition can shave down earnings. In the KASH group meeting, women complained that some sex workers charge just 50 or 100 Kenyan shillings. That’s less than $1 USD. “No sex for 100 shillings,” one woman said. “We do not want to be cheap.” Someone suggested creating a kind of union, convincing all local sex workers to agree on set prices.

During the heated Luo conversation that followed, I wondered if a union was a real option. Sex work in Kenya seemed to be a free market, with zero regulation and a high demand for youth. Aluna told me that she—like most Kenyan girls entering sex work—started on her own, without oversight from a pimp or brothel. She explained the ups and downs of the trade, including the “dry season,” during school holidays. That’s when most of the usual clients disappear to buy sex from girls around 14, who try to make money during their break. Kenya has a steady supply of adolescent girls who need cash, and the sex market seems to thrive on them. Research shows they’re not all selling sex to survive; some are just seeking the minor luxuries of modern life: a better pair of jeans, a cooler cell phone.

None of them were at our meeting because, according to Aluna, teenage girls usually try to keep their sex work a secret. They’re hard to reach. I thought of the only time I’d met a young sex worker—years ago, volunteering with a street outreach NGO in Puerto Rico. She was maybe 13, and so drugged that she staggered toward us. I wanted to do something, to protect her somehow. Instead, I handed her a sandwich.

It’s easy to sanitize sex work when you’re researching it from Boston, looking up public health data and analyzing the trends. In person, the reality—that a sizable number of women and girls are selling access to their more intimate body parts for the amount I spend on a large latte at home—unnerved me in a way I didn’t expect.

I wondered how funders of HIV prevention programs—particularly those based in offices far away from the “hot spots” of Kisumu—would react if they actually spent time with sex workers. Historically, for example, the US government has funded sex worker-focused projects with serious reservations, as evidenced by the “anti-prostitution pledge” that NGOs used to have to agree to when they received HIV/AIDS-related grants. (The Supreme Court struck down that policy just last summer.) Would visiting Aluna and the other sex workers foster more compassion? Less?

As the meeting wound down, the women started talking about ways out of sex work. Vocational training was available at a partner NGO, someone said. The woman with the swollen eye asked in a hushed voice if she might be eligible. The KASH officer asked her how old she was. She responded: “23.” Unlike many women in the group, she would just qualify under the age cap of 24.

I found myself exhaling, relieved. I thought she deserved a job that didn’t involve a high risk of getting raped and kicked in the face. A viable way out seemed to be what many sex workers wanted, too. Aluna was trying to get a loan to start a poultry farm with other sex workers. They would supply eggs and chickens to the hotels where they rented rooms and sold sex.

The shame associated with sex work remains, even among women who seem to earn a decent income. Through KASH, Aluna was advocating for the rights and respect that sex workers desperately need—but she also told me she didn’t want her real name on record. She didn’t want her kids to find out what she does. One child wants to be a pilot; another, an artist. More than anything, Aluna told me, she wants them to finish school—to do what she did not.

Maybe this is a difficult truth about sex work, one that public health researchers often gloss over. Aluna is empowered. She does what she needs to do to support her family. But she is not proud.

Elizabeth Daube is a freelance writer based in New York City and communications officer at American Jewish World Service. The views expressed here are entirely her own. In the US and in the developing world, she's worked as a journalist and with researchers and nonprofit programs focused on health, gender, violence and poverty. You can follow her on Twitter @lizdaube.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!