Indonesia’s ‘liberal’ president is about to execute more drug smugglers

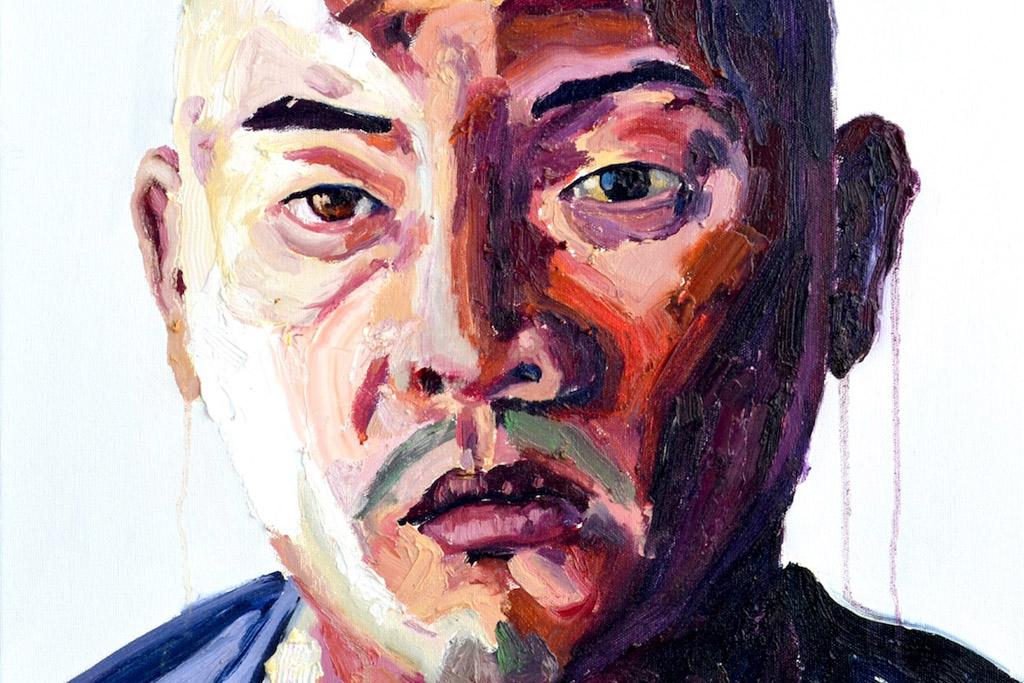

Australian artist Myuran Sukumaran's depiction of his co-accused, Australian Andrew Chan.

Editor's note: This story was originally published on Feb 8, 2015. Indonesia's government on April 23 ordered preparations for two Australian drug smugglers, Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran, to be executed by firing squad.

JAKARTA, Indonesia — When Indonesia’s president rejected his clemency plea in early January, Myuran Sukumaran stopped painting for a week. “He was in tears,” said his friend and artistic mentor Ben Quilty.

“He said I haven’t missed a day of painting since the day I’ve met you three years ago,” recalls Quilty, a well-known Australian artist fighting to keep his compatriot from being executed by firing squad.

“I said Myuran, what are you doing, sitting on your ass. Get amongst it, you’re wasting your time and maybe you don’t have much left, and every day, you’re missing out on the opportunity of continuing your practice.”

Ben Quilty acts tough when he’s with Sukumaran, but he says this is the “hardest thing” he’s ever done.

They first met in 2011. Sukumaran had sent a letter to Quilty from his jail in Bali, where he has been since he was arrested in 2005 for attempting to smuggle eight kilos of heroin to Australia. “He asked me for the most simple tips on how to use paint in the way that I use it, in very thick gestural marks.”

Quilty was moved by the letter, and curious. He asked to come visit Sukumaran, and the prisoner agreed. Three years later, Quilty recalls perfectly this first meeting.

“I was obviously very anxious … there is a stereotype of a drug smuggler around the world, someone who’s very bad and evil.”

That wasn’t Sukumaran.

“He was quiet, very humble, very thankful that I was there and extremely keen to learn from me … and he’s never wasted one second of our meetings on self-pity.”

The two became friends, and Quilty came to visit and teach Sukumaran as often as he could.

He calls Sukumaran’s progress over the years “dizzying.” “He has all the techniques, he’s nailed them … he draws honestly as well as me.”

Quilty also got very involved in a “mercy campaign” for Sukumaran and his co-accused, fellow Australian Andrew Chan.

Both have now had their presidential clemency plea rejected and Indonesia’s attorney general said they will be amongst the next convicts to be executed. No date has yet been set, but they could be only days away from facing the firing squad.

Indonesia’s anti-drug legislation is one of the toughest in the world. Six drug convicts were executed in January, including five foreigners, despite international pleas for mercy.

Human rights defenders were stunned. Many had hoped Joko “Jokowi” Widodo would be the president to boost human rights in the country. After all, as the first leader without links to previous dictator Suharto’s regime, he was to be the symbol of change in Indonesian politics. As a presidential candidate, he had repeatedly promised to make human rights a priority.

But less than three months after Jokowi took office, it appears that executions of drug convicts are a more pressing matter.

During an interview with CNN last month, he explained: “Imagine, every day we have 50 people die because of narcotics, of drugs. In one year, it's 18,000 people who die because of narcotics. We are not going to compromise for drug dealers. No compromise. No compromise.”

Indonesia, he had previously said, is “in a state of emergency” and needs “shock therapy.”

That’s why the authorities announced 20 executions of drug smugglers in 2015, and that’s why, as Jokowi confirmed on CNN, “there will be no amnesty for drug dealers.”

The problem, specialists say, is that the president’s plan simply won’t work.

According to Human Rights Watch’s Asia director Phelim Kine, Jokowi makes a “serious mistake in his assessment of the facts.”

“All studies show that death penalty for drug convicts doesn’t work as a deterrent,” he insisted during HRW’s World Report 2015 launch in Jakarta. More than 30 Indonesian organizations working with drug addicts sent a letter to the president to argue the same case: Death penalty and executions of drug convicts they wrote, “have failed” to reduce the numbers of drug trafficking and of drug addicts in the country.

Kine also notes the “extreme hypocrisy” of the Indonesian authorities, who spend fortunes to save Indonesians on death row abroad from being executed, particularly in Saudi Arabia. Last April, the government paid nearly $2 million in “blood money” so a domestic worker convicted of killing her Saudi employer would be spared.

Why should clemency only apply to those on death row overseas, asks Kine, calling death penalty “cruel, barbaric, unacceptable.”

While Sukumaran and Chan have exhausted all legal recourse and their chances appear to get slimmer by the day, their families and supporters refuse to give up hope.

As Andrew’s brother Michael Chan told Australian media in January, “they were young kids, stupid kids that made a stupid mistake, that have showed over the last 10 years they have changed and reformed themselves.”

Sukumaran was arrested on his 24th birthday, Chan was 21.

Australian Prime minister Tony Abbott said both showed to be “reformed characters,” and “deserve mercy.” Andrew Chan, who his brother says is a “totally different” person, is now studying to become a pastor.

“I don’t expect him to come home tomorrow,” Michael Chan said in the same interview. “They both have done a crime and they both should pay for it, but not with their lives.”