The future looks bright for solar power in India

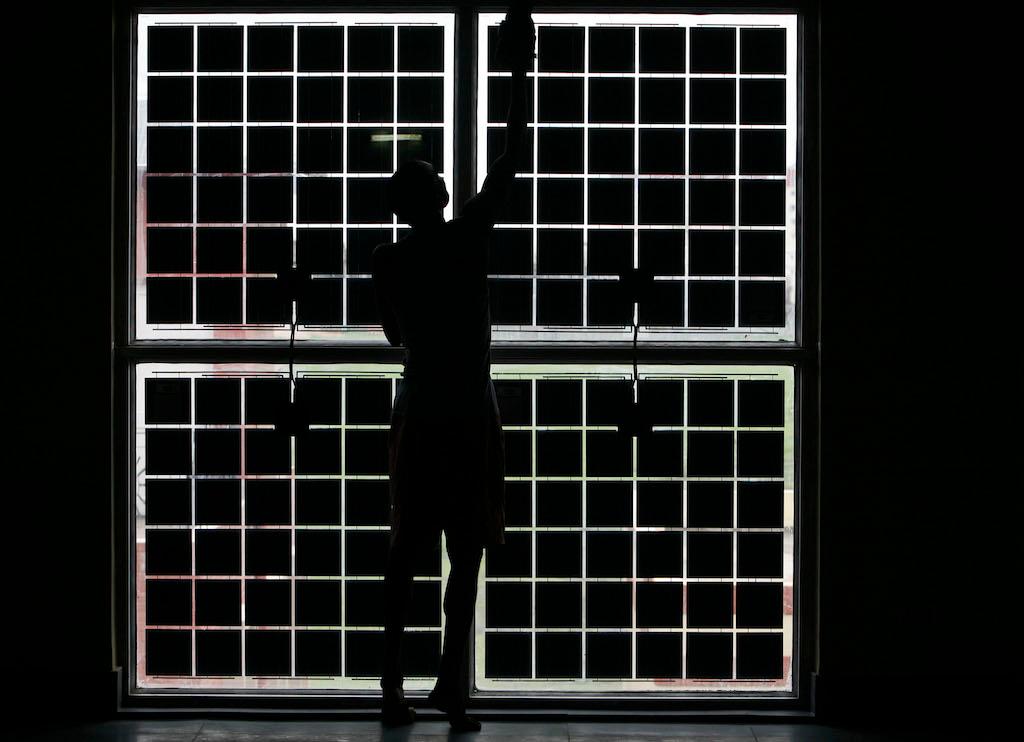

A laborer cleans solar cells in a newly constructed solar housing complex in Kolkata, July 8, 2008.

NEW DELHI, India — Free speech in cartoons can get tricky. The Australian newspaper learned a lesson about what crosses the line in December, when a cartoon in its pages drew international accusations of racism.

Something about the stereotypical illiterate Indian trying to eat — with mango chutney — solar panels sent by the United Nations just didn’t elicit a laugh.

While international media criticized the jibe, the cartoon raised, albeit inappropriately, a question that may well be on the minds of many in India and elsewhere.

The government wants to produce more than 10 percent of all energy from solar sources within just seven years from now, and over 25 percent by 2030. And yet India struggles with poor infrastructure, relies on coal for 61 percent of its power consumption, and a fifth of its population lives in poverty. Can it really afford a major shift to expensive solar power?

The Indian government and the country’s solar innovators are optimistic. Last month India committed to the Paris agreement to reduce emissions and helped found the International Solar Alliance, a group of 120 countries committed to expanding and improving the use of solar power technology. Earlier this year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government raised India’s solar capacity goal to 100,000 megawatts by 2022. The target is an ambitious 20 times current production. If India can meet it, it will become one of the biggest solar powerhouses in the world.

“With about 300 clear, sunny days in a year … the solar energy available exceeds the possible energy output of all fossil fuel energy reserves in India,” a senior official in the Ministry of Power, who asked not to be named, told GlobalPost.

Competitive bidding on India’s solar projects have allowed companies like the US-based SunEdison to offer the lowest-ever price per unit for solar energy in India, at 7 cents per kilowatt-hour. And a rising number of start-ups, encouraged by the government’s support, are stepping in to India’s solar market.

“Given the scale at which the Indian government wants to promote solar, making it reach every household, the timing to switch to solar has never been more conducive than it is right now,” said Samarth Wadhwa, the founder of Sun Bazaar. “Now solar has penetrated into the customers’ minds.”

Wadhwa believes that solar power can be more reliable than the government’s current coal-dependent power supply. His company reaches out directly to urban customers online, allowing consumers to choose how much they want to invest in solar energy, suggesting products that match those prices and installing them in their houses.

“The cost of thermal power is also appreciating, and if we take that into account the cost of a solar system for a household will repay itself within five years,” said Wadhwa.

It isn’t just urban, middle- or upper-class India that can reap these long-term benefits. Infrastructure, ranging from roads to power plants, is poor in rural India — but that is exactly why “off-grid” solar projects are finding success in remote villages.

“To find solar street lights or roof-top mounted solar panel, with battery and associated wiring in the home or shops for lighting and other appliances is a common sight in rural areas now,” said Shyam Patra, the founder of Naturetech Infra. The company provides solar energy directly to rural homes and small and micro enterprises in India’s poorest states, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. “Even petrol pumps and mobile towers operating in rural areas are going for solar power,” he added.

The government is trying to help, too. According to the government official, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy offers a 30 to 40 percent subsidy for the cost of solar lanterns, home lights and small systems.

“Around 20 million solar lamps are expected by 2022,” the official said. “These typically replace kerosene lamps and can be purchased for the cost of a few months’ worth of kerosene through a small loan.”

Despite the support from the public and private sectors, solar power still has a few hurdles to cross before it really takes off in India. Both Sun Bazaar’s Wadhwa and Naturetech’s Patra point to the lack of quality control on solar products as one of them.

“There are a lot of cheap and low-quality products coming in from China,” said Wadhwa. “That erodes consumer confidence in solar, because these systems are known to fail.”

According to the power ministry official, strengthening transmission lines and improving grid infrastructure will also be crucial. Patra added that costs are pushed up because providing services to small rural projects is currently expensive.

For once, though, India’s massive population may actually be an advantage in bringing costs down. “If we look at what SolarCity is trying to do in the US, if it is economical for them at their limited scale, it will obviously be economical to India at the scale we have.”

For now, it looks like no chutney will be necessary.