A Daughter’s Journey: Reflections on Mother’s Day

I remember the day my mom died. The night before, we’d fallen asleep together in her room. I was wrapped up tight in my Princess Jasmine sleeping bag at the foot of her bed as she slept delicately next to my grandmother.

Then everything changed.

I woke up the next morning in a panic on the floor of my own bedroom, still zipped in my sleeping bag, while my dad slept on my bottom bunk. When I got up and ran for the door my dad suddenly awoke. He tried to stop me, but before he could say a word, I’d already run down the hallway into my parents’ room. She wasn’t there. I stared at her empty bed for what seemed like forever.

No one had to say a word. I knew she was gone.

Today is Mother’s Day. It is also my 25th birthday. And it is 20 years since I stood in the doorway of my parents’ bedroom not understanding why my 35-year-old mother had just died from AIDS.

Even now I can’t say that I fully understand why she died or why my father and I are HIV free, but I can say that I am learning to answer questions about the life my mother may have lived had she been diagnosed at a time when HIV wasn’t a death sentence.

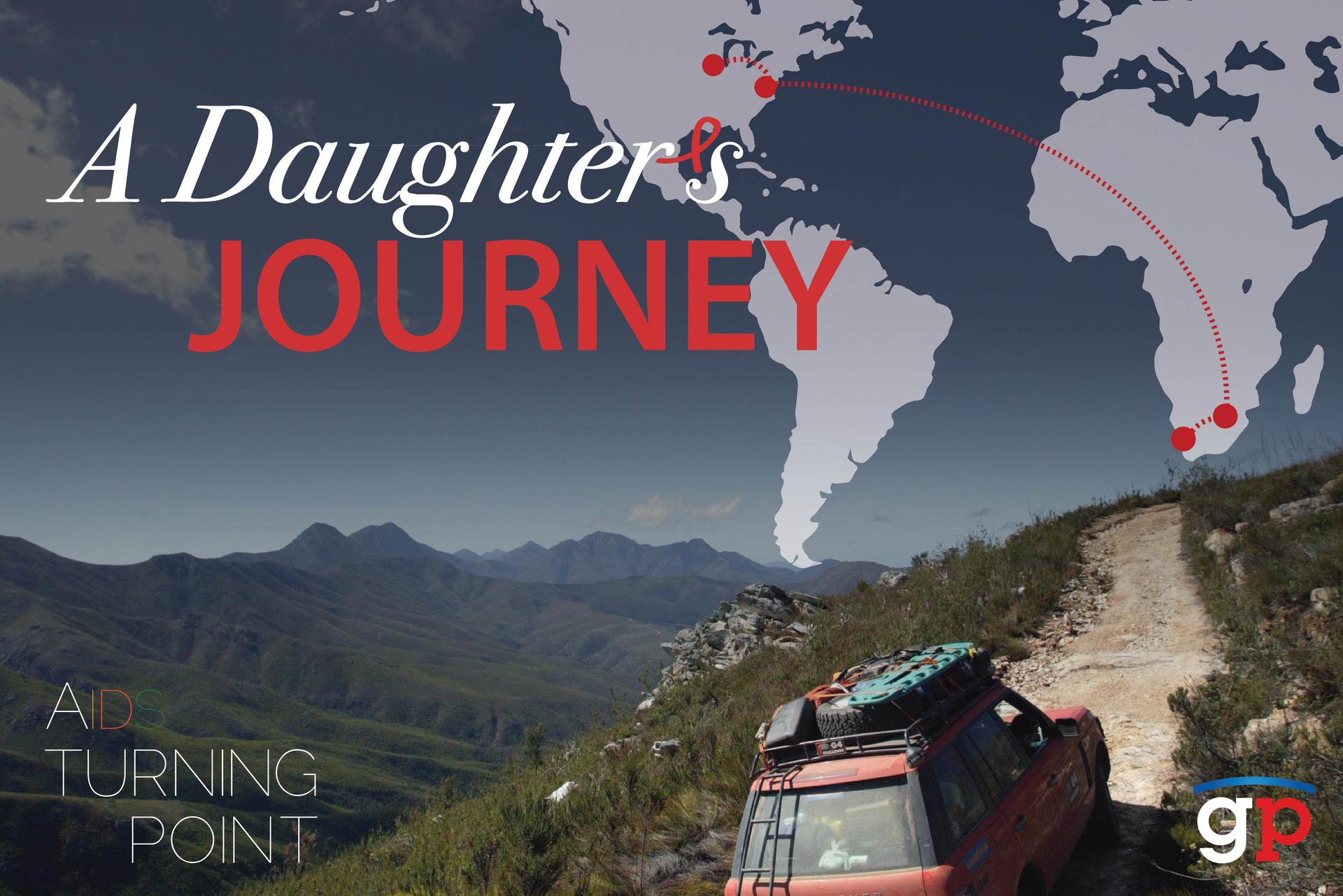

Many of these answers came in 2012 when I set out on a reporting journey for GlobalPost across two continents to document the lives of women, in particular mothers, living with HIV. The strength and courage illuminated in their daily lives made me proud of who I imagined my mom would be. Having HIV didn’t mean a life of unhappiness, but instead a life helping and caring for others—including me.

In my hometown of Chicago I interviewed my family about what it was like to learn my mom was HIV positive and to take care of her knowing people would judge her and that she would die. In New York I met with a mother and daughter who were educating women in their East Harlem community about how to live healthily with HIV. Susan and Christina Rodriguez’s quest was motivated by their personal experiences; both women were also infected with the virus. Halfway around the globe, in Cape Town, I spent time with another HIV-positive mother, Nozi Samela, who was dedicating her life to mentoring other mothers with the virus and helping them learn to take care of themselves and their newborn babies.

Two years later, I caught up with these courageous women.

Starting a new chapter in Cape Town

“I’m sorry to say that you have missed a lot,” Nozi said to me, laughing, when she picked up the phone earlier this week. Hearing her familiar voice took me back to South Africa where we’d met for the first time—I can still remember the salmon colored coat she was wearing that day, her infectious smile, and her bubbly laugh.

It was July 2012 and she’d recently become a communications associate for mothers2mothers (m2m)—an international nonprofit organization that educates and trains HIV-positive mothers to help other HIV-positive women who are pregnant. It also sets up mentorship programs aimed to prevent mother-to-child transmission of the virus. At the time, Nozi also had just found out she was pregnant with her second child.

I never would have known that Nozi was living with HIV when we met. She looked happy and healthy, she was glowing, and she was thriving in her career. But that was not always the case. When Nozi first came to m2m 8 years earlier, she told me, she was just 19, six months pregnant with her first child, and recently diagnosed with HIV.

With the help of m2m, Nozi changed her life. She gave birth to a healthy baby boy and went on to become one of the program’s mentors, sharing life-saving knowledge about how women with HIV can stay healthy and protect their babies from contracting the virus.

But three years later – five years before I met her – Nozi’s life changed again when her toddler son was killed in a car accident.

“I hated the organization,” Nozi told me in 2012 as she looked back on her son’s death and her role as a m2m mentor mother at the time. “It was called mothers2mothers and I was no longer a mother.”

Over time, however, Nozi began to redefine what being a mother meant to her and to her peers. She didn’t leave m2m. In fact, she became more involved.

“Mothers2mothers is not just about helping women accept their HIV status, or about helping women give birth to HIV-negative children, but it is helping women go on with their lives,” she said in 2012. “It is helping women understand that being HIV-positive is not the end of life, but actually a beginning of a new chapter.”

Today, Nozi’s newest chapter includes redefining motherhood through her baby girl, Mbali, who was born in November 2012.

“All over again things have changed for me,” she said. “Motherhood for me this time is learning–it’s a journey. Now, it is not just about nurturing and giving love or support, it’s learning a new person all over again.”

The journey has been an emotional one. Nozi had a complicated delivery, leaving her with no feeling in her body for reasons that the doctors could not diagnose. The numbing sensation made nursing impossible. As doctors tried to figure out what might have gone wrong, Nozi hospitalized and Mbali in the hands of nurses who would have to give her formula. Nozi was concerned, with good reason. Formula is against the World Health Organization’s instructions for HIV-positive mothers who, like Nozi, intend to breastfeed exclusively, because it can increase the risk of transmitting the virus. Nozi recovered and decided to breastfeed, but little Mbali needed to be tested.

“I will be honest with you, I was scared. I was terrified,” Nozi said of taking Mbali to the clinic. “I knew that I had taken my treatment; I knew I had done everything right, but then I still knew that even if the mother takes antiretroviral drugs and does everything right there is still a 2 percent chance baby could be infected.”

The test results took a week to get processed. It was the scariest week of Nozi’s life.

“The day I went to clinic to fetch the results I didn’t hear anything the counselor said to me. I was praying that if anything could change now, let it be changed,” Nozi said. “I knew if she was HIV positive nothing could change at that moment, but I was praying for [a] miracle.”

The test came back negative.

An ambassador for HIV-positive women around the world

With the help of m2m Nozi was able to not only learn her HIV status, but ultimately how to live a healthy life and protect both of her children from contracting the virus.

“Our prevention of mother to child transmission efforts are paying off, but there are some countries where there’s a long way to go,” said m2m co-founder and international director, Robin Smalley.

Since 2012, m2m has brought on a new CEO, Frank Beadle de Palomo, and under his leadership the organization has expanded its services. In addition to preventing mother to child transmission (PMTCT), it addresses more general maternal and newborn health issues facing women in sub-Saharan Africa, such as other infectious and chronic diseases.

“Our mothers are now being trained to do TB testing, to give referrals for cervical cancer screening, to raise awareness about malaria prevention, and to determine malnutrition,” Smalley said.

M2m is also working with the governments of Malawi an Uganda, where HIV is particularly virulent and access to healthcare can be limited, to develop and launch community-based mentor programs so that rather than having to go to different clinics for different services, as women currently must do, m2m would provide one-stop testing and support.

As a new mom, Nozi wants to help m2m in its new mission and hopes to use the coming years to travel abroad as an ambassador for the organization.

“I may have saved my daughter from HIV, and other women have saved their children, but there are so many women giving birth to HIV positive children, which is so unfair,” Nozi said. “I feel that I still have a role to play in advocating for mothers living with HIV in the entire universe.”

A new drive for an East Harlem community

On the other side of the world, in East Harlem earlier this month, I visited Christina Rodriguez and her mother, Susan. It was my first time visiting their organization's new office in a local community center. I walked up the stairs to Susan’s office and immediately, the nerves I felt were washed away when I was greeted with a warm hug from Christina. Susan sat behind her desk. She too got up and hugged me. I felt like I was home.

When I first met Christina two years ago, I couldn’t help but compare our stories. We were roughly the same age. She was five when her dad died; I was five when my mom died, too. Susan had contracted HIV from Christina’s dad; my dad did not contract HIV from my mom. Christina was HIV positive; I was not. In my mind we were opposite sides of the same coin.

Like Nozi, Susan, could help me envision the life my mother might have had if she had lived, but unlike them, Christina was the only one I knew who could show me what my life might had been had I been born positive.

Christina was the only one of her two siblings to contract the virus. But she did not shy away from her diagnosis. Her HIV-positive status propelled her to help other kids in the same situation, and she and her siblings founded a youth program under SMART, the community-based group that Susan had founded in 1998. SMART University (Sisterhood Mobilized for AIDS/HIV Research and Treatment) is an educational organization run by and for HIV-positive women to help educate and encourage healthy living.

When I first met Susan and Christina, SMART served nearly 500 people and struggled to find consistent forms of funding. Since then, the organization has expanded. It has moved from an HIV support group building to a more central location in East Harlem, allowing the SMART women to tap into other community organizations to share resources and cater to more people. While funding is still a struggle, SMART now helps close to 750 people and SMART Youth has more than 65 members. Just last spring, the organization was selected by community vote to receive $180,000 in capital funding for a mobile cooking classroom and emergency response center.

“This district has one of highest rates of obesity, poverty, asthma, and cardio vascular disease,” Susan said. “It’s really important that we bring what we know to the community in terms of healthy eating and cooking, so we feel this would be very critical component of what SMART does.”

SMART also has been working with Harlem Community & Academic Partnerships (HCAP) to become “research ready,” a technical designation that would allow SMART to collect data on their programs to assess and then share the impact they are having in the community.

“Government and academic institutions have their own criteria for assessing effectiveness of programs, so a lot of community-based organizations get left out when talking about effecting change,” said Janet Carter, SMART’s program director. “Becoming research ready is about bringing us and what we do to the table.”

SMART plans to take a deep dive into the data it has been collecting about its participants to see what it can do to help make a difference in terms of policy change. Susan will give a presentation on SMART’s journey to becoming research ready at the next International AIDS Conference this July in Australia, and Christina plans to go with her.

Both women admit that there are challenges when it comes to managing SMART while dealing with family growing pains: Christina hopes to graduate from college next semester and is navigating a long term relationship with her boyfriend. Susan is helping another daughter raise two young boys and is supporting Christina’s younger brother as he finishes college as well. Despite what comes their way, neither Christina nor Susan will rest until SMART is able to make a visible and lasting difference in the lives of those living in their community.

“When she talks about this mobile kitchen project this is when she’s shining and glowing,” Christina said of her mother. “This is the aspect of SMART that has rejuvenated her. This project, that’s her drive right now.”

“I hit the jackpot with my kids. They are great kids. I’m proud of Christina in what she does and that whatever she says comes out of Christina not out of me,” Susan said. “I’m just amazed. I’m continually amazed at what all three of my children do.”

The journey continues

I promised Susan, Christina and Nozi that I would do a better job of keeping in touch this time. I think of the three of them often. Each time I hear their stories, that gaping hole that emerged as I stood staring at my mother’s empty bed is filled up a little bit—made a little smaller by their love for life, their love for their children, and by the pieces of their lives that they have chosen to share with me.

More from GlobalPost: A Daughter's Journey, Part 1: Seeking answers on HIV/AIDS

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?