China’s New Great Game

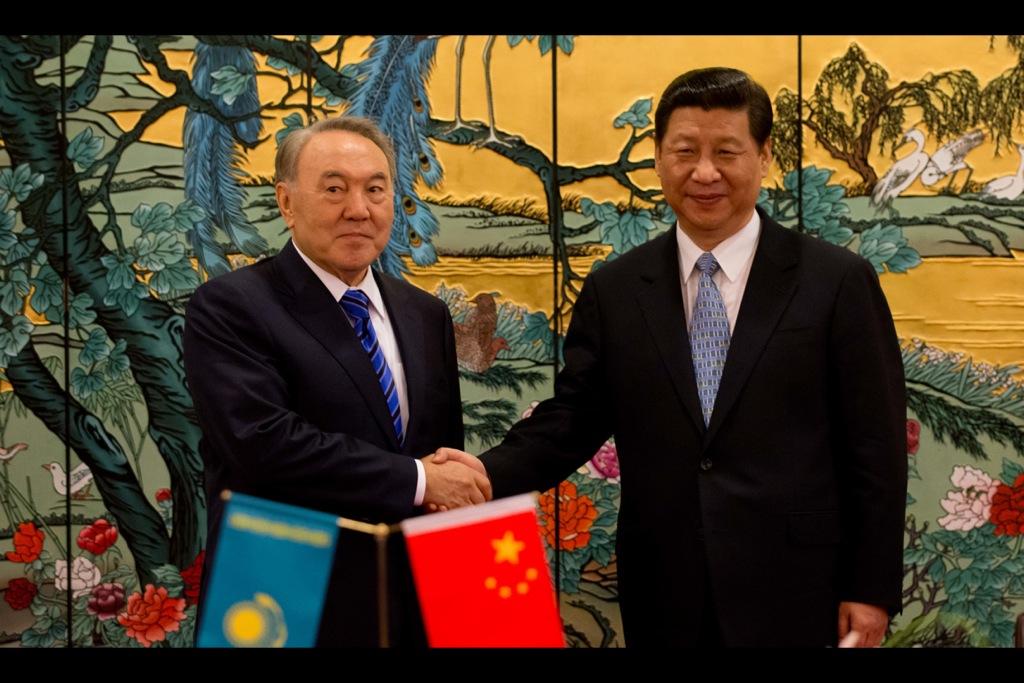

China’s President Xi Jinping (R) and Kazakhstan’s President Nursultan Nazarbayev shake hands following a signing ceremony in Sanya on the southern Chinese resort island of Hainan on April 6, 2013.

HONG KONG — For centuries, global powers have flexed their muscles across greater Central Asia, jockeying for supremacy over its rich resources and strategically knotty landscape. In the 19th century, Great Britain and czarist Russia competed in the so-called Great Game, fought largely by spies and saboteurs. In the 20th, the United States waged proxy war in the vast, rugged region against the USSR; following communism’s fall, Washington, DC, launched a costly aid offensive to draw the newborn countries into its sphere of influence.

Now, Beijing thinks it’s China’s turn.

In a series of highly publicized visits over the last week, General Secretary Xi Jinping has toured Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Kyrgyzstan, signing massive energy deals and proclaiming China’s desire to create a “Silk Road Economic Zone” to cement ties with the region.

On Sept. 13, Xi’s grand tour ends with a gathering of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which counts Russia, China, and the four Central Asian States as members.

So what does China think it has to gain by embroiling itself in one of the most tangled, contested regions on the planet?

The first motivation is energy. China depends heavily on imported energy to fuel its growth, and the states of Central Asia can supply oil, minerals, and natural gas in exchange for investment.

China has already helped fund and build two oil and gas pipelines through Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. During Xi’s visit, Kazakhstan agreed to $30 billion in new agreements, including a $5 billion stake for China in a Caspian Sea oil field that is believed to be the biggest outside Saudi Arabia. Turkmenistan welcomed Xi to the opening of a gas processing plant that China lent $8 billion to build.

The second, and perhaps biggest, motive is internal security. China's far western province of Xinjiang, an area populated by Muslim, ethnically Turkic Uighurs, has become more restive as China has encouraged the migration of Han Chinese who dominate the local economy. By cultivating better ties with Xinjiang’s neighbors, China hopes to snuff out potential bases of sympathy and support for Uighur independence.

This is a hardly straightforward task. China is viewed warily in the region, and America’s upcoming withdrawal from Afghanistan could further destabilize China’s borders.

“The problem is that large parts of Central Asia look more insecure and unstable by the year,” says a recent report by the International Crisis Group. “Corruption is endemic, criminalisation of the political establishment widespread, social services in dramatic decline and security forces weak. … There is a risk that Central Asian jihadis currently fighting beside the Taliban may take their struggle back home after 2014. This would pose major difficulties for both Central Asia and China,” the report says.

For what it’s worth, Xi scored headlines on security as well. Uzbekistan signed off on a joint declaration to fight “terrorism, extremism, and separatism” and lift trade to $5 billion by 2017. Kyrgyzstan, the last stop, received promises to upgrade a power plant in exchange for its vow to oppose Taiwanese independence.

The third motive behind the Silk Road push is to erase Russian and American influence in what China views as its backyard. To do this, China has been willing to spend big. Since 2002 China’s trade with the region has grown from roughly $1 billion to more than $28 billion in 2010 — almost twice Russia’s total that year. Today, China is the pre-eminent economic force in Central Asia.

“China is simply playing this kind of grand chess game so as to balance against Russia and America,” says Simon Shen, professor of international relations at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “China does not want [Central Asia] subverted by the Americans. If a democratic transition happened quickly, China would see this as evidence of subversion or counterrevolution.”

Finally, Xi’s purposes may not be solely geopolitical. As is often the case in China, domestic political concerns often come first. Shen suggests that Xi may be trying to show audiences at home that he is strong, confident, and indisputably in charge at a time when Bo Xilai’s trial and anti-corruption purges have revealed divisions within the Communist Party leadership.

“He has done a lot of outgoing since assumption of duties, which is a bit unusual, since the preference has usually been given to domestic policies,” Shen says. “I think he is going in part to show that he has a firm control of power and to enhance his image in the domestic community.”

For the moment, China's relations with Central Asia seem stable and mutually beneficial. But as the People's Republic becomes more economically tied to the countries' autocratic regimes, it may not be able to avoid the messy political or military problems that have snared great powers in the past.

“Only China will have the economic strength and political goodwill to make peace, as well as the resources to fill the coming power vacuum," says Ahmed Rashid, a Pakistani journalist and Central Asia expert. "But the question is whether it will be willing to take responsibility."

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!