2014: A year of electoral fireworks

Earth’s voting season begins.

NEW YORK — Some of the largest nations on Earth — along with some of the most violent — will hold important elections in the coming year, any of which could affect the global political landscape profoundly.

The United States has entered a midterm election year, with all the sound and fury (and distortion) that brings.

But in a world now dotted with democracies, that’s only the start. National votes in Indonesia, Afghanistan, Egypt, India, Colombia and Brazil should command significant attention as all have the ability to improve or set back global growth and stability.

In the huge democracies of India, Brazil and Indonesia, corruption and lowered growth expectations will dominate political debate. Brazil’s opposition parties seem weak so far, but voters in the two Asian giants look likely to spark a power change after more than a decade of consistent rule by one party.

Colombia, Iraq and Afghanistan hope their new governments can draw a line under years of internal violence, though hopes seem more strained in Kabul's case. South Africa and Turkey, two emerging market powers that have suffered instability in the past year, also elect new parliaments.

And in Egypt, an interim regime promises parliamentary polls in the spring and a presidential ballot in summer — all against a backdrop of questionable legitimacy and violent protest by the Islamists ousted after winning the last national elections.

Here is a quick look at how these votes are shaping up:

Afghanistan: April 5, 2014

![]()

An Afghan woman shows her inked finger after casting her vote in September 2010 in Kabul. Paula Bronstein/Getty Images

Afghanistan’s presidential vote is particularly fraught as the country faces the withdrawal of remaining NATO forces (and important deadlines for negotiating any continuing deployments by United States and European forces).

Hamid Karzai has served as Afghan president since December 2001, shortly after US troops toppled the Taliban regime, and is constitutionally barred from running again. He has refused to sign a treaty to allow a smaller follow-on foreign force to remain, saying only the next president has the authority to do so — and thus further raising the stakes for the vote.

The US and its allies will be happy to see Karzai go, and blame him for failing to extend the central government writ and for tolerating high levels of corruption. Yet his exit could shine a light on the extent to which Karzai kept a lid on even greater chaos. Over a decade of investing Western blood and treasure hang in the balance.

Brazil: Oct. 5, 2014

![]()

Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff casts her vote in October 2012 municipal elections. Marcos Nagelstein/AFP/Getty Images

Plummeting economic growth rates have forced new burdens on the country’s state-run oil giant, Petrobras, on which the left-leaning government increasingly relies for social spending commitments.

This led many major independent oil companies (IOCs) to forego the much-touted bidding round for Brazil’s deep-water oil fields.

All this comes at a busy time for Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff. Her ties to the US are strained (or more accurately, constrained) by revelations that the National Security Agency has been tapping her phone and those of many other Brazilians. Building stadiums and other infrastructure for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics is behind schedule, over budget and a constant source of complaint from working people who have other ideas for how the national wealth might be spent. Epic protests over transport fare hikes and a host of other grievances that ripped through the country in June and July could shake soccer’s biggest global event starting one year later, which could prove politically devastating.

Still, Dilma — as Brazil’s first female president is widely known at home — seems secure unless a major economic crisis (perhaps touched off abroad by US Federal Reserve tapering) or a repeat of last summer’s street violence intervene.

India: May 1, 2014

![]()

Hoping for Narendra Modi. Sajjad Hussain/AFP/Getty Images

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and his Congress Party have governed India since 2004. But on Friday, Singh said he will not serve another term and threw his support behind his party’s pick Rahul Gandhi to win the May election.

A Gandhi victory is looking difficult. Opposition candidate Narendra Modi, the governor of Gujarat state, is ahead in the polls.

The election, which is held over a period of months in India’s various states, could also raise the possibility of serious political unrest. Modi has never shaken off allegations that he sat on his hands during communal violence in 2002 in which at least 790 Muslims in his state died. Several of his rallies already have been hit by bombings and rioting.

But Modi has also turned his state into a kind of powerhouse — “the Ruhr of the Raj,” as one German economist put it, referencing the famous industrial regions on the German-French border. Gujarat, with less than 5 percent of India’s population, accounts for 25 percent of its exports. With GDP growth now barely 5 percent annually, that’s a record voters can warm up to.

Indonesia: July 9, 2014

![]()

Metallica's man in Jakarta, Gov. Joko Widodo. STR/AFP/Getty Images

In Southeast Asia’s largest country, Indonesia, the decade-long run by President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono will also come to an end since the country’s constitution prohibits a third five-year term. Jakarta Gov. Joko Widodo leads polls, but his Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) is deeply split on his candidacy. Whether or not Jokowi (as he’s known) will be PDI-P’s standard-bearer is up to one person, the enigmatic former president and PDI-P boss, Megawati Sukarnoputri. The problem is, she may herself want to run, leaving Jokowi to decide whether to go it alone.

The race in July — and an earlier April parliamentary vote — is drawing huge attention from multinationals that have invested heavily in the Indonesian economy in recent years but are weary of its corruption. A sweeping new anti-corruption code and other regulatory regimes pertinent to the country’s large mining and palm oil industries are in play amid a major influx of both Chinese and Japanese investment.

Iraq: April-June 2014

The lead-up to national assembly elections in Iraq coincides with a surge in violence that’s brought bloodshed to levels not seen since 2007. Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki’s won the right to run for a third term when the supreme court scrapped term limits.

But Maliki’s popularity, as well as his ability to control his coalition, is flagging. Still, no obvious rival has emerged from within the majority Shia Muslim community, and politicians from the opposing Sunni Islam faction may opt to back a third Maliki term to prevent a further descent into chaos. The Kurds, once again, find themselves kingmakers.

Colombia: May 25, 2014

![]()

Can Colombia's Juan Manuel Santos win again? Eitan Abramovich/AFP/Getty Images

Colombia’s politics have come to resemble a Latin American soap opera. President Juan Manuel Santos is popular and looking likely to be re-elected in the spring parliamentary and presidential vote.

But an open feud with his former mentor and predecessor, Alvaro Uribe, has spawned a new opposition party to Santos’ right that looks certain to win many seats — among them for Uribe himself, who is seeking to become a senator.

At issue is the final lap in long-running peace negotiations with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, the country’s largest leftist rebel group known as the FARC. After previous failed attempts, the new peace talks that started in February 2012 in Cuba have finally reached critical mass. The concessions Santos has made, including provisions for amnesty and a political role for demilitarized FARC leaders, angered Uribe, who as president boasted big military wins on the battlefield against the guerrillas. So far the talks have survived, but the election could determine whether they reach accord or if this is just another short pause in the country’s decades long warfare.

South Africa: Between April and June 2014

![]()

Voters wait for hours in a long line to cast their ballots in national elections in April 2009 in Alexandra Township, South Africa. John Moore/Getty Images

The lionization of Nelson Mandela has focused South Africans on what made their nation such a hopeful exception to Africa’s history two decades ago. But next spring, the country must face more contemporary questions, including whether to give Mandela’s African National Congress (ANC) the same overwhelming majority in parliament it has enjoyed since the first post-apartheid election.

Most analysts expect the ANC to lose ground, but not enough to imperil its near-total control of the country’s politics.

The Democratic Alliance, an opposition party led by moderate whites and disaffected former ANC personalities, may gain. But when parliament reconvenes to choose a new president, ANC incumbent Jacob Zuma will almost certainly prevail. Unless, that is, he is impeached for corruption.

Turkey: August 2014

![]()

Turkish Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan arrives at his office in Ankara. Adem Altan/AFP/Getty Images

Term limits mean that Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan must relinquish his post this year. Until recently, his supporters talked confidently about overturning that rule and allowing Erdogan to stay in power.

But his increasingly imperious rule — particularly the bloody crackdown on protesters in Istanbul last summer — has dented his reputation badly, and indeed set back Turkey’s larger image across the region.

Erdogan will almost certainly win in August’s presidential polling, though the constitution grants the president only ceremonial powers. Then again, that’s true of the prime minister’s post in Russia, and anyone who remembers Prime Minister Vladimir Putin can imagine a similar scenario in Ankara. If that is to be possible, Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP in Turkish) needs to hold its own in state and local elections in April, too.

The United States: Nov. 4, 2014

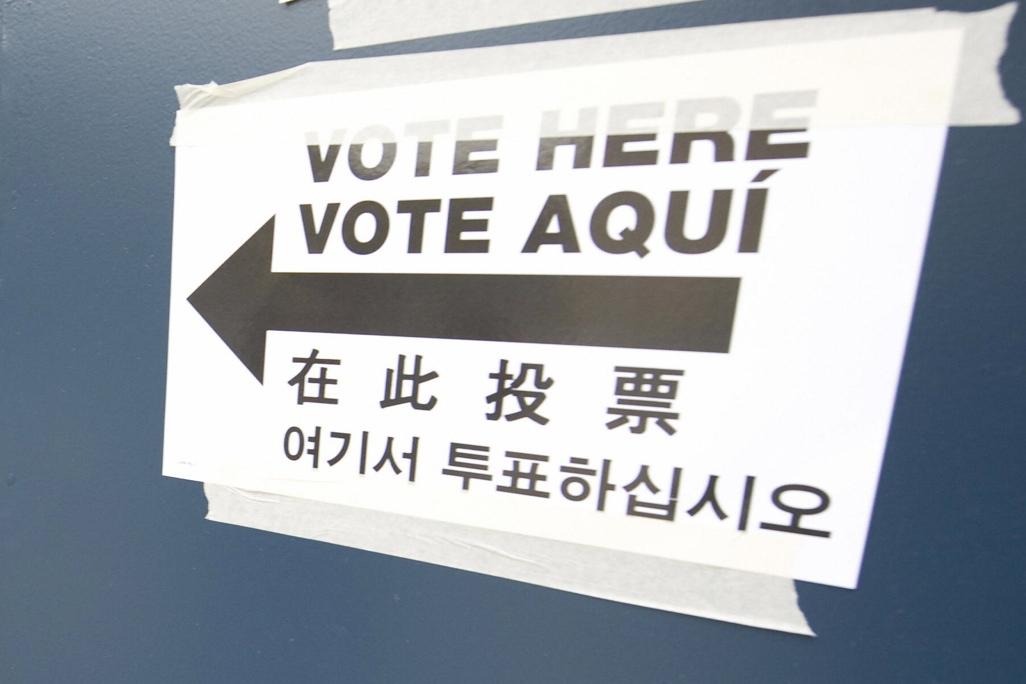

![]()

On the vote again. Kevork Djansezian/Getty Images

Perhaps the most pivotal vote of the coming year may not even involve a head of state: the terribly deadlocked US Congress faces a midterm election in which all of the 435 seats in the lower chamber (the House of Representatives) and 33 of the Senate’s 100 seats will be contested. Historically, the opposition party gains ground in midterm cycles, a legacy that should bode well for the Republicans with Democratic President Barack Obama halfway through his second term in the White House.

But a long-simmering civil war within the Republican movement broke into plain view in the autumn of 2013. The right-leaning Tea Party faction coerced centrists to shut down the US federal government in an effort to force the president to rescind the 2010 Affordable Care Act, known as “Obamacare,” due to come into force in 2014. While the initial efforts to enroll millions of Americans have been plagued by computer problems, public opinion polls after the government shutdown show deep disdain for the Republicans. With the Tea Party apparently unrepentant, Obama’s Democrats may retain the Senate (where they currently hold a 56 to 44 majority) and even gain a bit of ground in the House (where the Republicans hold a 33 seat majority).

Besides the usual fireworks, the midterms’ outcome will have important implications for the direction of the world’s largest economy. A Republican success in taking the Senate would consign Obama to the wilderness in his final two years in office and presage a move toward European-style fiscal austerity. If the Democrats hold onto the Senate and close the House gap, fiscal stimulus and a more muscular approach to global financial reform may be back on the table. Such a result could also breathe new life into the largely rhetorical US “pivot” toward Asia, blunting expected Tea Party opposition to the Trans-Pacific Partnership free trade talks and its Occidental cousin, the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).

Update and correction: In India, decade-long Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has ruled out serving another term. In Indonesia, a previous version of this article mistakenly described Jakarta Gov. Joko Widodo as a candidate of the Golkar party. He is a member of the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!