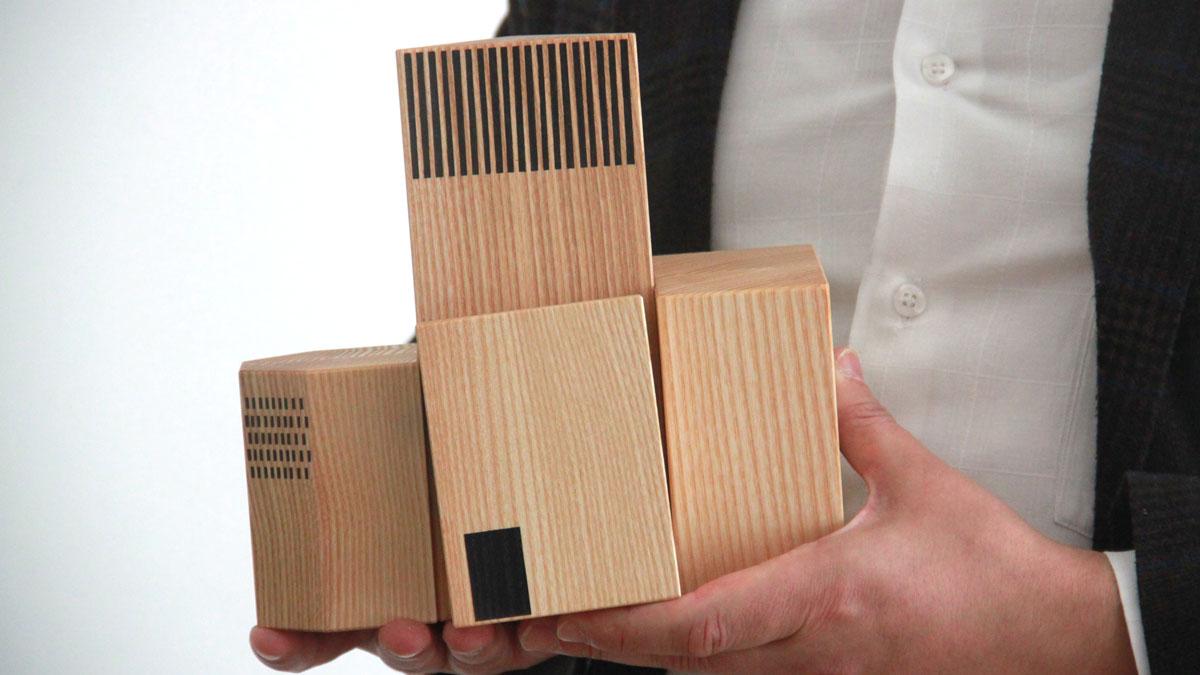

Imam Kadir Sanci holds a model of the House of One in Berlin.

Have you heard the one about a priest, a rabbi and an imam who build a house of worship together?

It’s not a joke — it’s the House of One, an ambitious plan to build the world’s first hybrid church-synagogue-mosque in the German capital of Berlin.

The idea began with an archaeological discovery: The ruins of Berlin’s very first church, built in the 13th century, and destroyed and rebuilt repeatedly throughout history.

In the 1960s, communist officials in East Berlin, who had no interest in religion, demolished it, and a parking lot was built in its place.

Berlin officials were redeveloping the area recently when they stumbled upon the medieval foundations.

On a recent drizzly day, Pastor Gregor Hohberg of St. Mary’s, a Lutheran church a few blocks up the road, stood next to the remains of the medieval church, today covered with sand to protect the ruins.

Hohberg said members of his parish were so moved by the discovery, they held a worship service on top of the ruins.

“When we came to this place there, we just felt this energy,” said Hohberg. “We felt a responsibility to deal with this authentic place.”

But Pastor Hohberg had to deal with reality, too: Most people in Berlin are secular. Rebuilding Berlin’s oldest church in the center of the city might not be welcomed.

So he came up with the House of One, an idea he thought the city would support. It would feature three chapels for the three monotheistic religions, surrounding a shared hall.

Like the fall of the Berlin Wall, Hohberg said the House of One would tear down the walls between religions, with each religion keeping its own identity. The clergy would support gender equality, tolerance for gays and interfaith dialogue.

His parish liked the plan. City officials did too.

He quickly found Jewish partners, including Rabbi Andreas Nachama, who heads Berlin’s only liberal Reform Jewish congregation.

Rabbi Nachama said he joined the House of One in part “to prove that three religions could really live peacefully together.”

It took two years to find a Muslim partner for the project, said Pastor Hohberg. That partner is interfaith activist Imam Kadir Sanci.

“People here have fears about Muslims, about Islam,” said Imam Sanci. “It’s a chance for us to show them we are peaceful people.”

Imam Sanci explained why other Muslim clergy may have declined to participate in the church-synagogue-mosque hybrid.

There are two schools of thought among devout Muslims, he said. One school believes that everything in life is forbidden unless the Quran and Muslim teachings allow it.

His school of thought is the opposite: “all the things in the world are allowed,” he said, except for what the Quran and Muslim teachings forbid.

“I’m looking at this project and say — there’s nothing forbidden,” he said. “It’s possible.”

When the House of One is built, who will come? The three clergy hope it will attract a mix of tourists and locals, and that it will be a hub of interfaith activities.

But Imam Sanci said he believes if the House of One were standing today, the majority of Berlin’s Muslims, who are of Turkish origin, would likely avoid his prayer service.

That’s because Imam Sanci is affiliated with the teachings of Turkish Muslim cleric Fethullah Gülen, a major foe of the Turkish president in recent years.

Those affiliated with Gülen’s movement have been facing a major crackdown in Turkey. Muslims of Turkish origin in Berlin tend to align with the Turkish president, Imam Sanci said.

With regard to the Jewish community, because Rabbi Nachama leads the city’s only Reform synagogue, he said he might not attract those from other streams of Judaism.

“I mean, that’s what it is. You know, we take each person as he is,” Nachama said.

“We’ll see what happens,” he added. “Whether this project will be accepted or not, I mean, it’s much too early to discuss it. I mean, let’s first have a building, and then we will see whether this project can succeed.”

Not one brick has been laid yet for the House of One. The clergy said they won’t start building until they raise 10 million euros.

They’ve raised about a million euros so far, from Jews, Christians and Muslims from around the world.

Their ultimate goal is to raise about 40 million euros — which Rabbi Nachama said was “almost mission impossible.”

The clergy has a crowdfunding site, and they’re applying for German government funding.

Now they’re hoping they’ve got a prayer.

Frank Hessenland contributed to this report.