Wildfires like Alberta’s are fueled by climate change

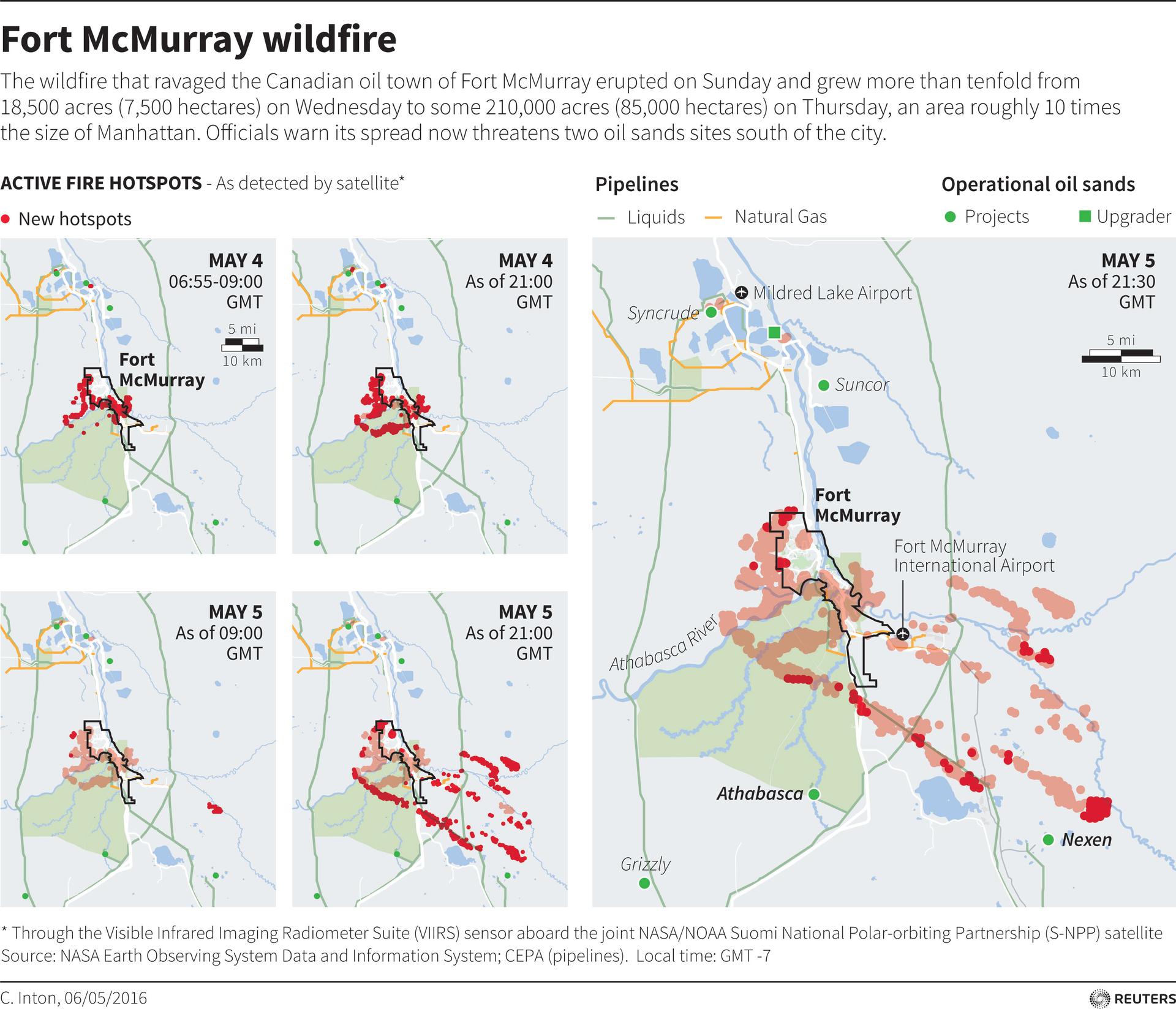

A massive wildfire, which caused a mandatory evacuation, rages south of Fort McMurray near Anzac, Alberta, Canada May 4, 2016.

The giant wildfire in Alberta, Canada, rages on.

All 88,000 residents of the remote town of Fort McMurray have evacuated, many of them driving along a wall of fire to do so.

"Coming out of Fort McMurray,” said evacuee Neil Scott, “there was fire on the hillside, I could feel the heat through the car. The flames were 10 or 15 feet from my vehicle."

Efforts to control the fire with helicopters and air-tankers have been foiled by high winds rapidly spreading flames. Dozens of fires in the province have engulfed 250,000 acres of forest and destroyed 2,000 homes in the area surrounding Fort McMurray.

Alberta Premier Rachel Notley has declared a state of emergency and warned Thursday that residents of the city face a long wait to return home.

"I must be very, very direct about this," she said to AFP. "It is apparent that the damage to the community in Fort McMurray is extensive, and the city is not safe for residents at this time."

The climate change context

This fire is an acute crisis for residents of Fort McMurray, but for the rest of the world, it’s a reminder of a larger, slower-moving phenenomen: climate change.

In the last 40 or 45 years, the area burned by wildfires in Canada has doubled, according to Mike Flannigan, a University of Alberta professor of wildland fire.

“This is the result of human-caused climate change,” Flannigan said. “We are seeing more fires on the landscape, and the fires are more intense than they used to be.”

Flannigan said warmer temperatures lead to more forest fires for three reasons:

A longer fire season

“The warmer we get, the longer our fire season is,” Flannigan said.

In Alberta, the fire season started this year on March 1, a month earlier than it used to start.

More lightning

The warmer it gets, the more lightning we have. That’s because a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, and moisture is needed to start a lightning bolt.

The more often lightning strikes, the more frequently it can start forest fires.

As temperatures warm, the atmosphere’s ability to hold moisture increases

That means evapotranspiration, or the evaporation of water from soil and plants into the atmosphere, increases.

“It’s like the atmosphere gets more efficient at sucking the moisture out of the fuel, the stuff that burns,” Flannigan said, “so it’s easier for the fuels to catch fire and spread fire.”

Weather variations also play a role

Climate change provides a backdrop for more severe and frequent wildfires over time, but it’s difficult to pinpoint the exact contribution of a warming climate to any individual fire. This year’s weather patterns also fuelled the Fort McMurray fire. It’s an El Niño year, which in western Canada means warm and dry weather conditions.

This drier-than-normal winter left little snowpack on the ground, and what remained melted quickly in warmer temperatures. That left the soil and vegetation dried out and susceptible to fire.

A snowball effect

The massive Alberta forest fires have created a pyrocumulonimbus cloud, which has unleashed a massive fire thunderstorm there. The lightening generated by these storms is starting new fires in the region.

“So we’ve got the fire generating more fires,” Flannigan said.

Longer-term, timber and especially carbon-rich peat burned in forest fires add greenhouse gasses to the atmosphere.

On some days of 2015, peat fires in Indonesia emitted more greenhouses gases than the entire US economy.

Boreal forests in Canada, Alaska, and Siberia have about 30 times more peat than Indonesia, according to Flannigan.

“There’s the potential for significant release of greenhouse gases from peat fires and forest fires, and this could make it even warmer,” Flannigan said.

For now, the human toll of this fire is still front and center for crews fighting it and families displaced by it. In Edmonton, where Flannigan lives, evacuees are already arriving at their new homes.

“I’m expecting that we’ll see 20,000 to 30,000 evacuees here, and this is going to be a long-term process,” Flannigan said. “Some of the kids are already going to school here because it may be months, may be years before things get back to normal in Fort McMurray.”

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!