Cherice Harrison Nelson, right, with her aunt, who is a bishop at a Spiritual Church in New Orleans. The spiritual church has also adapted the St. Joseph’s tradition, and builds elaborate altars.

Every day for a few weeks leading up to St. Joseph’s Day on March 19, David Roe coordinates a daily bake at his home in New Orleans’ St. Roch neighborhood. Volunteers drop in and help bake and decorate traditional Italian cookies, all of which will go on the St. Joseph’s altar at St. Augustine church.

Some of the best are the crumbly, fig-filled cucidatti, which David describes as an ancient predecessor to the Fig Newton.

Sandra Scalise Juneau, who’s Sicilian and also a baker, is a local expert on the tradition. She says this whole thing dates back to the Middle Ages.

“The legend is that back in the 12th century, maybe earlier — there was a famine in Sicily. Sicily had been the bread basket for Rome, so you can imagine these people were starving.”

The Sicilians prayed for relief from the famine to their patron saint, Joseph. In the meantime, the only thing that would grow were fava beans, usually reserved for animal feed. But desperate times call for desperate measures, and the fava bean kept the Sicilians fed through the drought.

When the rains finally came, the Sicilians attributed their good fortune to St. Joseph and pledged to thank him with an elaborate feast — pretty much forever. But they didn’t forget the fava bean, either.

“The fava bean became the symbol of their hope and is known in New Orleans as the lucky bean,” Juneau explains. “If you go to a St. Joseph’s altar you’ll always get a fava bean and people will keep them in their pockets and purses as a sign of good fortune.”

Juneau says the fava bean is probably a stronger tradition now in New Orleans than even in Sicily. That’s because Sicilians arrived in large numbers to New Orleans around the turn of the 20th century. Many of them built altars in their homes and storefronts on St. Joseph’s Day. They’d go from house to house, each marked with a palm frond out front to indicate who had an altar inside.

“I can remember as a child, the tradition was to make the nine altars,” Juneau recalls. “You could actually walk to nine altars all in the same evening because they were all right in the same neighborhood, you know!”

While the tradition has Sicilian origins, its observers don’t always.

St. Augustine church is the oldest black Catholic parish in the country. When David Roe heard the church needed help baking for its altar, he decided to lend a hand. After all, he says, back in the day, the parishioners at St. Augustine helped his ancestors.

“The Sicilians were considered even by other Italians to be the lowest of the low,” Roe says. “The Sicilians were not allowed to worship in the major churches, and the first church that took them in was St. Augustine church in the Treme.”

Beverly Curry, who’s in charge of the St. Joseph’s altar at St. Augustine, grew up in the Treme, around the corner from the church. She tries to honor the Sicilian origins of the holiday.

“On St. Joseph day, you don’t cook food with meat, but we have all the meatless dishes that the Italians ever cooked. And they [are] so good. Lord I can’t eat that but it’s good. Hoo! The Italian cabbage and the Italian fish and the shrimp balls — ooh baby it be good!”

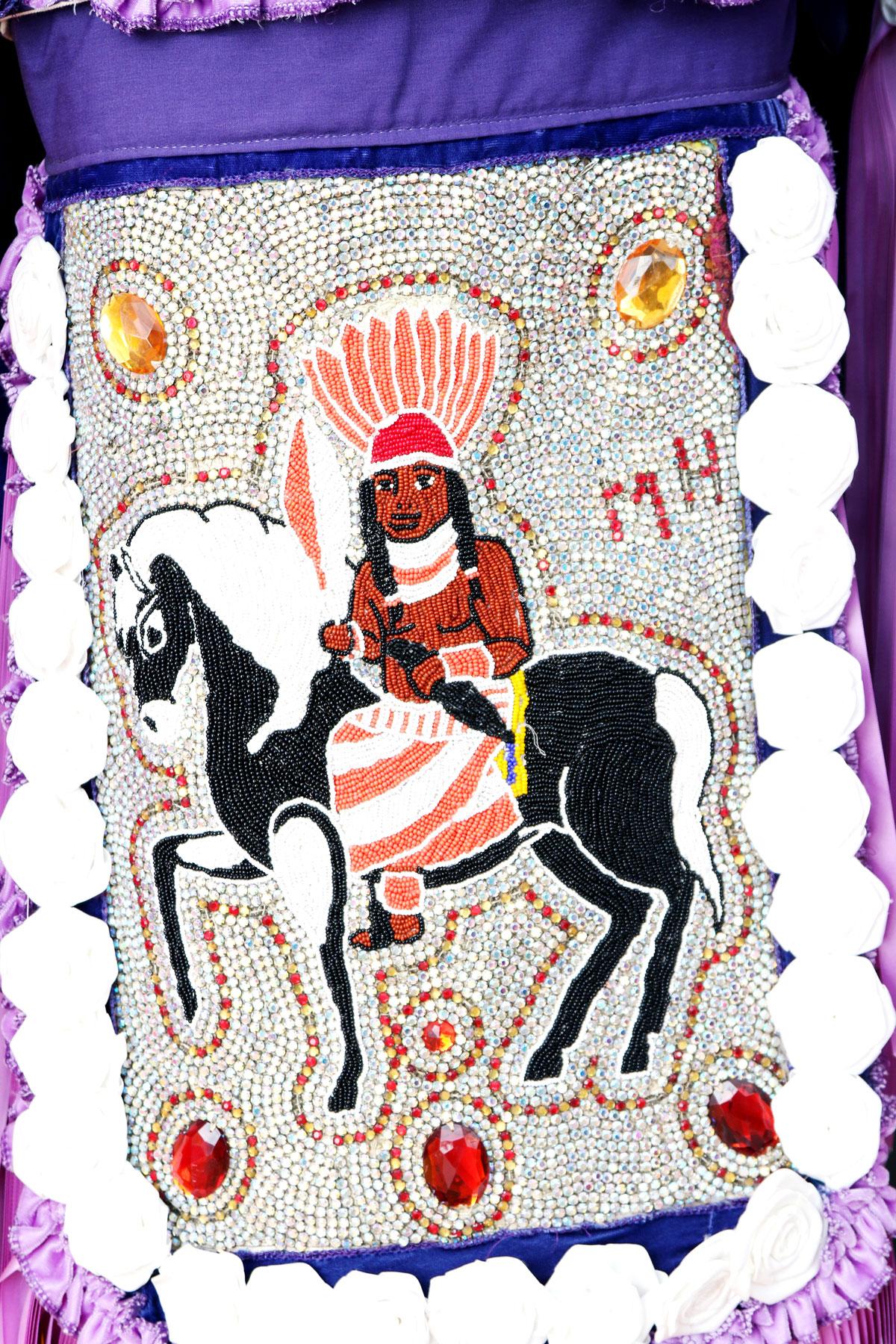

Not everyone is such a purist, though. For some, St. Joseph’s Day has taken on a totally new meaning. Cherise Harrison Nelson grew up in a family of Mardi Gras Indians. If you’ve never seen them, the Mardi Gras Indians are groups of African Americans who dress as Native Americans on Carnival Day. Each year, the Indians spend countless hours sewing elaborate suits of beads and feathers by hand. They parade through the streets in their suits and meet each other in a sort of ritualized, theatrical battle.

Traditionally, you hear about the Indians parading and singing on Mardi Gras. But, Nelson says, “The only other time you really see that is on St. Joseph’s night.”

Nobody knows exactly why the Mardi Gras Indians chose St. Joseph’s as the other day of the year to come out. There are a couple theories.

One dates back to when Sicilians and African Americans used to live in the same neighborhoods. For Sicilians, St. Joseph Day was a day off from the austerity of Lent — you built your altar and celebrated — it was the one day during Lent you could even get married.

So, some speculate that the Mardi Gras Indians picked up their Sicilian neighbors’ tradition, and took advantage of the break in Lent to take their suits out for one last spin. But all of that is speculation. What we know for certain is that even today, St. Joseph’s is a holiday that transcends cultural lines.

On a recent Saturday, Sandra Juneau led a cucidatti baking workshop at Xavier University in New Orleans, which is historically Black and Catholic. She tried to give the students a sense of why it’s important.

“In every culture, the making of dough, the baking of bread is the most communal act,” Juneau told the class. “Every culture. So for us to be baking bread together — to be making these beautiful cakes together — I think is about the most loving thing we can be doing together.”

The cucidatti will go on Xavier’s altar, which is also topped with a West African Kente cloth.