The current El Niño may hold lessons for how to deal with a warming planet

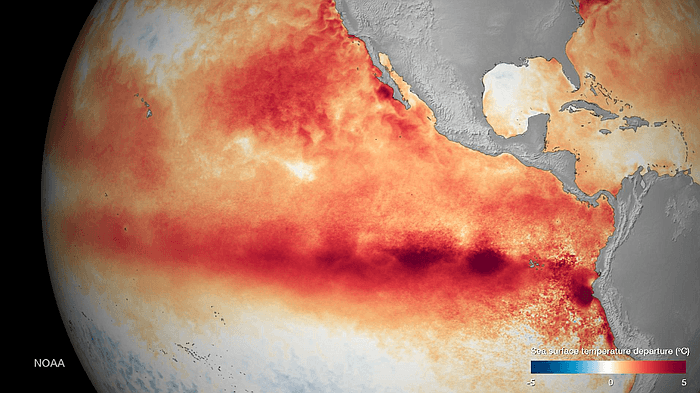

El Niño is the name given to unusually warm ocean waters in the equatorial Pacific, seen above in red. El Niño effects weather patterns across the globe.

The extreme weather events unfolding around the world as a result of El Niño may give nations an opportunity to learn how to plan for the expected effects of global warming.

“In some sense, what we're seeing around the world right now is an advanced view of the sort of things that we'll see more of in the future — all of the weather systems being somewhat more vigorous than they have been in the past, the risk of both droughts in some regions and flooding in other regions,” says climate scientist Kevin Trenberth of the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

El Niño is essentially a “mini global warming" event, Trenberth explains. It arises from a build-up of heat in the waters of the equatorial Pacific Ocean. The warm ocean waters and higher sea levels begin in the western tropical Pacific and then spread to the central and eastern Pacific. The warm tropical ocean releases additional water vapor into the atmosphere through evaporation.

When warm air rises from the oceans to higher levels of the atmosphere, the moisture in the air “rains out,” in a process called “latent heating of condensation.” As that moisture gets released, it leads to additional warming of the air and invigorates weather systems around the world, especially in the eastern Pacific. What’s more, changes in ocean temperature become amplified over dry land, according to one study.

The effects of an El Niño can be overwhelming: The summer of 2015 saw a record number of hurricanes and typhoons in the Philippines, Japan, China, Taiwan and Vietnam — the largest number of Category Four and Five storms on record by a substantial amount, according to Trenberth.

Changing weather patterns also brought a major drought to Indonesia, with a tremendous number of wildfires, while here in the US, major flooding occurred along the Mississippi River, especially in the state of Missouri. In fact, Trenberth says, during November and December the state of Missouri had three times its normal rainfall. The previous record had been about twice the normal amount of rainfall.

All of this means that countries around the world and some states in the US need to take lessons from this relatively short-term surge in temperatures and begin planning to cope with the more persistent, long-term changes likely to arise from climate change, Trenberth says.

Heavy rainfall in California, for example, will bring substantial relief to agriculture and help restore the parched soil in many parts of that state. But unfortunately — in this case — California has a well-developed system of flood protection, which means a lot of the water now flowing back into Southern California runs into the Los Angeles River and back out to sea, instead of going back into the earth to replenish groundwater supplies.

So now, Trenberth says, the issue uppermost in people’s minds is the storage of water in reservoirs, rivers and lakes.

“This relates to how we work with water in the United States,” Trenberth says. “There is one group that is designed to prevent floods, but there's another group who deals with droughts, and these two need to get together so that they save the water from the times when there’s too much for the times when there isn’t enough — and that's the thing which is really missing at the moment.”

Improvements in climate science now give the world much more notice than ever before about the likelihood of El Niño occurring. Scientists predicted this El Niño more the 18 months ago. This would have been a good time to have mechanisms in place to capture all of this year’s extra rain or to plan for the increased risk of wildfire in Australia, Trenberth says.

Some places in the world are indeed making changes. “They actually change the crops they grow, the seeds they plant, the fertilizer strategy, the irrigation strategy, [how they] manage hydroelectric power — all of these kinds of things,” Trenberth says.

Trenberth believes the current El Niño may have peaked in November in terms of the magnitude of the unusual sea surface temperatures out in the tropical Pacific, so its effects may begin to subside soon.

“It's certainly going to be with us through March, but by about April it's expected that it will be fading quite substantially and it'll be basically gone by about June,” Trenberth says.

“This is the transition. It’s the normal length of time for an El Niño to last, so exactly how this plays out in the next few months, given that it's already beginning to fade a little bit, will be interesting to see — but often some of the biggest effects do occur around February across North America,” Trenberth cautions.

This story is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood