Zika reignites the debate on reproductive rights in Latin America

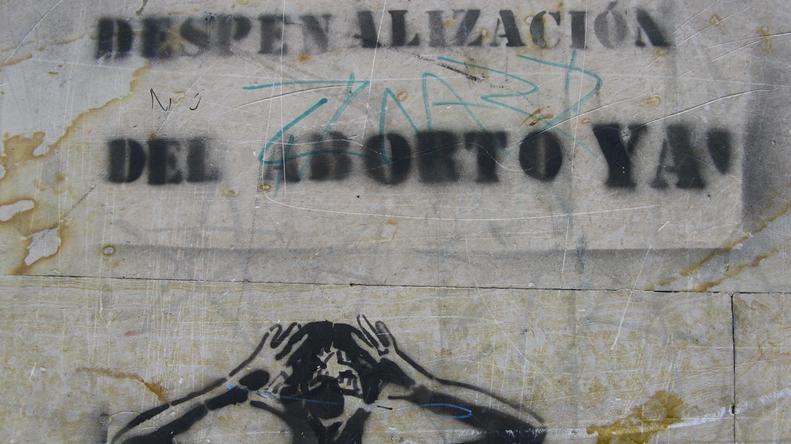

Graffiti in Bogota, Colombia, calling for the decriminalization of abortion.

Governments in Latin America are being criticized for urging women to avoid pregnancies as a means of curbing the Zika virus.

"Once again, governments put the burden on women to protect themselves from any risks," Paula Avila-Guillen, a programs specialist at the U.S.-based Center for Reproductive Rights, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. She said health ministries should also be addressing men's roles in the problem.

Monica Roa, vice president of strategy and external relations at the international rights group Women's Link Worldwide, which has regional offices in Latin America and Europe, said the burden should not rest on women alone.

"Women who are pregnant should have information about the possibility of interrupting the pregnancy if the law allows it in that country," Roa said in an interview with NPR on Jan. 27. "In the countries where the law doesn't allow for [abortion], I think the debate [about reproductive rights] should be on the table and discussed in the context [of the Zika infections]."

Roa calls for "massive campaigns" to inform both men and women about access to and use of contraceptives, something which has been lacking in the region.

Delayed Pregnancies

Women in at least four countries — Ecuador, El Salvador, Jamaica and Colombia — have been asked to delay pregnancies to avoid any potential congenital defects in their unborn children.

El Salvador recommended a two-year wait for women — until 2018 — after more than 5,000 cases of Zika virus were reported in the country in 2015 and early 2016, according to Reuters. Citing official figures, the story reports that 96 percent of women in El Salvador are suspected of having contracted the virus, but that no babies have so far been born with microcephaly.

"We'd like to suggest to all the women of fertile age that they take steps to plan their pregnancies and avoid getting pregnant between this year and next," El Salvador's Deputy Health Minister Eduardo Espinoza was quoted as saying in the same report.

Colombia suggests women delay their pregnancy by six to eight months. Colombia has the second-highest number of Zika infections after Brazil, where more than a million people have been infected.

"I believe it's a good way to communicate the risk, to tell people that there could be serious consequences," Colombia's Health Minister Alejandro Gaviria told The Guardian on Jan. 27.

But Roa, of Women's Link Worldwide, told NPR that proposals to delay pregnancy are riddled with false assumptions.

For one, 50 percent of pregnancies in Latin America are unplanned.

"We're saying that these recommendations are both naïve and ineffective, not only because of these unplanned pregnancies but because also they fail to take into account the prevalence of rape and sexual violence in the region, which also accounts for many of these not planned pregnancies," Roa said. "That's why the debate should be on the table."

The Zika virus, which is primarily transmitted through the bite of infected Aedes mosquitoes, is usually non-fatal but there have been reports that it can cause skull deformities and incomplete brain development in newborn babies.

Travel Alerts Issued

Pregnant women have therefore been advised to postpone travel to areas where Zika virus transmission is ongoing. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has specifically issued travel alerts to the following places: Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Suriname, Venezuela, Barbados, Bolivia, Ecuador, Guadeloupe, Saint Martin, Guyana, Cape Verde, Samoa and Puerto Rico.

The virus has now spread to 21 countries and is expected to reach all countries and territories in the Americas where the mosquitoes live, according to the World Health Organization.

In Colombia, women have the option of using emergency contraception or terminating the pregnancy legally. But that kind of health access is more the exception than the rule in the region.

"Most women — especially those in the most-affected areas—do not have clarity over these laws," Roa, of Women's Link Worldwide, told NPR. "There is a lack of information and there is a lack of access to these kinds of services and that is for the countries where these kinds of reproductive health services are legal."

Things are worse in conservative nations such as El Salvador, which is more than 50 percent Roman Catholic and where these services are illegal.

That's why Sara Garcia, a women's rights activist in the country, said the Zika outbreak has reignited the debate over the issue. "This should lead us to take up the discussion again and hopefully things will start to change," she told The Guardian.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!