Brazil’s impeached president: ‘I fought against human suffering, I battled inequality’

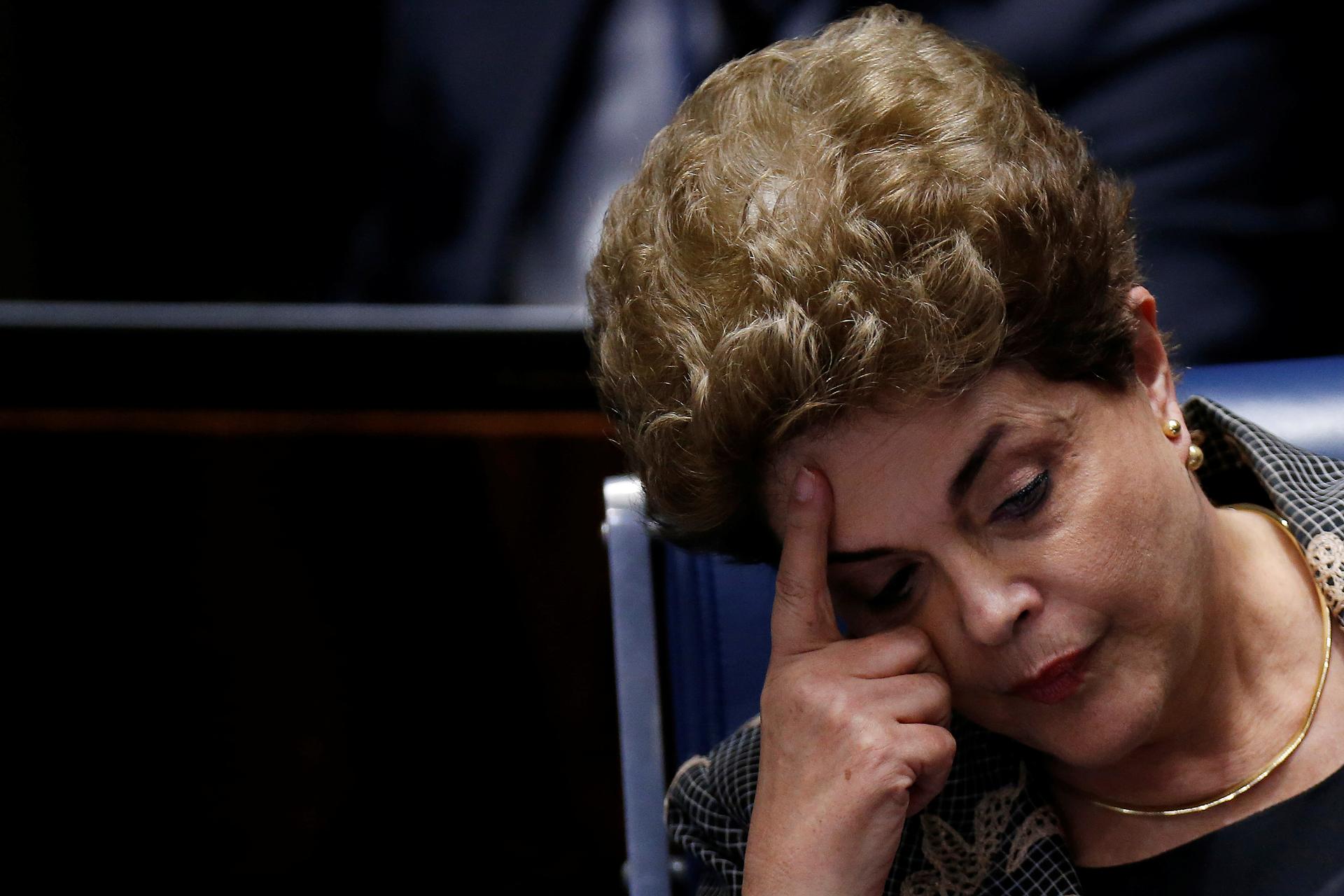

Dilma Rousseff at one of the final days of her impeachment trial this week before senators voted her out of office.

She looked more than angry as she finished her speech to supporters. She looked exhausted.

Dilma Rousseff, who led Brazil for six years, was removed from office on Wednesday after senators overwhelmingly voted for her impeachment.

Flanked by lawmakers and family who stuck by her throughout her impeachment trial, Rousseff walked into the presidential palace in Brasilia on Wednesday afternoon looking stunned, deflated and upset. She had just finished a defiant speech, denouncing the politicians who ousted her as misogynists and reactionaries, who seized power unjustly after losing four fair presidential elections.

“I did the best I could do,” Rousseff told assembled journalists and supporters. “I fought against human suffering, I fought against misery and hunger and I battled inequality.”

The senators said Rousseff is guilty of breaking “fiscal responsibility” laws by borrowing funds from public banks without congressional approval, as well as moving money illegally around government accounts to misrepresent state finances. She maintained to the end that she never committed these crimes and insisted the impeachment is about politics, not the law.

On that last bit, she has a point.

The five days of Senate debate and testimony were supposed to focus on the legality of what Rousseff did or didn’t do. Instead, the senators made grandiose speeches that covered everything from unemployment to God. Until the last moments before the vote, Rousseff’s opponents accused her of destroying the economy and fostering corruption, rather than tackle the sticky legal issues at hand.

Most of the senators who voted 61-20 to impeach Rousseff are themselves under criminal investigation. So is her former vice president, Michel Temer, who was immediately inaugurated as president on Wednesday evening. And so are the two men in line for president after him.

Temer, from the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, will serve out the rest of what would have been Rousseff's second term ending in 2018.

In a surprise move, the Senate also voted on Wednesday not to bar Rousseff from seeking public office for eight years. This had been part of the original planned vote, but at the 11th hour the Supreme Court justice overseeing the trial decided to split the issues into two votes: one asked whether she was guilty and should lose her mandate; the other asked if the eight-year ban should be imposed.

That means Rousseff can, in theory, run for public office. But it also sets something of a precedent for the dozens of lawmakers who themselves face removal from their offices: If a president can return from impeachment, maybe there will be hope for them when they’re kicked out, too?

Rousseff’s ouster ends an era in Brazilian politics. She is a protege of her predecessor Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, the wildly popular former president who left his two terms in office with sky-high approval ratings in 2010. Under “Lula” and “Dilma,” as they are known in Brazil, their left-leaning Workers' Party governments introduced reforms credited with lifting tens of millions of Brazilians out of poverty.

But the two presidents also presided over an era of rampant corruption in Brazil, the extent of which is still being unearthed by a group of newly empowered and popular prosecutors. Lula himself has become embroiled in the sprawling “car wash” scandal, a pay scheme involving politicians and executives at the state oil company. Prosecutors presented corruption charges against him last week.

On Wednesday, Rousseff vowed to fight on against powers that she said have undermined Brazilian democracy.

Lula will be key in this fight. He is widely expected to run for president again in 2018. It's still early but a recent poll showed he enjoys 29-30 percent of voter support — far more than any other potential candidate.

“If Lula comes back in 2018, nobody has a chance,” said Tia Zelia, a 62-year-old chef in Brasilia. “The people will vote for him because he’s human. He’s just different! He knows — there’s nobody in the world like Lula.”

As Rousseff prepares to leave her palace, the Workers' Party will need to tap into enthusiasm like Zelia’s. If it can do that, Brazil could see a return to the leftist party as soon as 2018.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?