From JFK to Black Lives Matter, he’s seen journalism up close. And he’s more optimistic than ever about it.

Peter Herford is a former journalist and executive at CBS News.

As an old year fades, you might take stock of what’s happened — to you, to things you care about. You might even look at what lies ahead. This is going to be one of those times — and the thing I care about in this case is journalism — and I’m going to take a long view.

Over the span of my lifetime, journalism has morphed, evolved, devolved, expanded, been degraded in some ways, improved in others. Everyone has an opinion on the state of journalism. Here’s one.

“In terms of the news flow, the availability of choice, all of the things that you want from the information flow — there’s no comparison. This is an infinitely better world. It’s also a more challenging world,” says Peter Herford, a former newswriter for Walter Cronkite, a CBS bureau chief in Vietnam, a CBS vice president, and then a teacher of future journalists in the US, Africa, Europe and China.

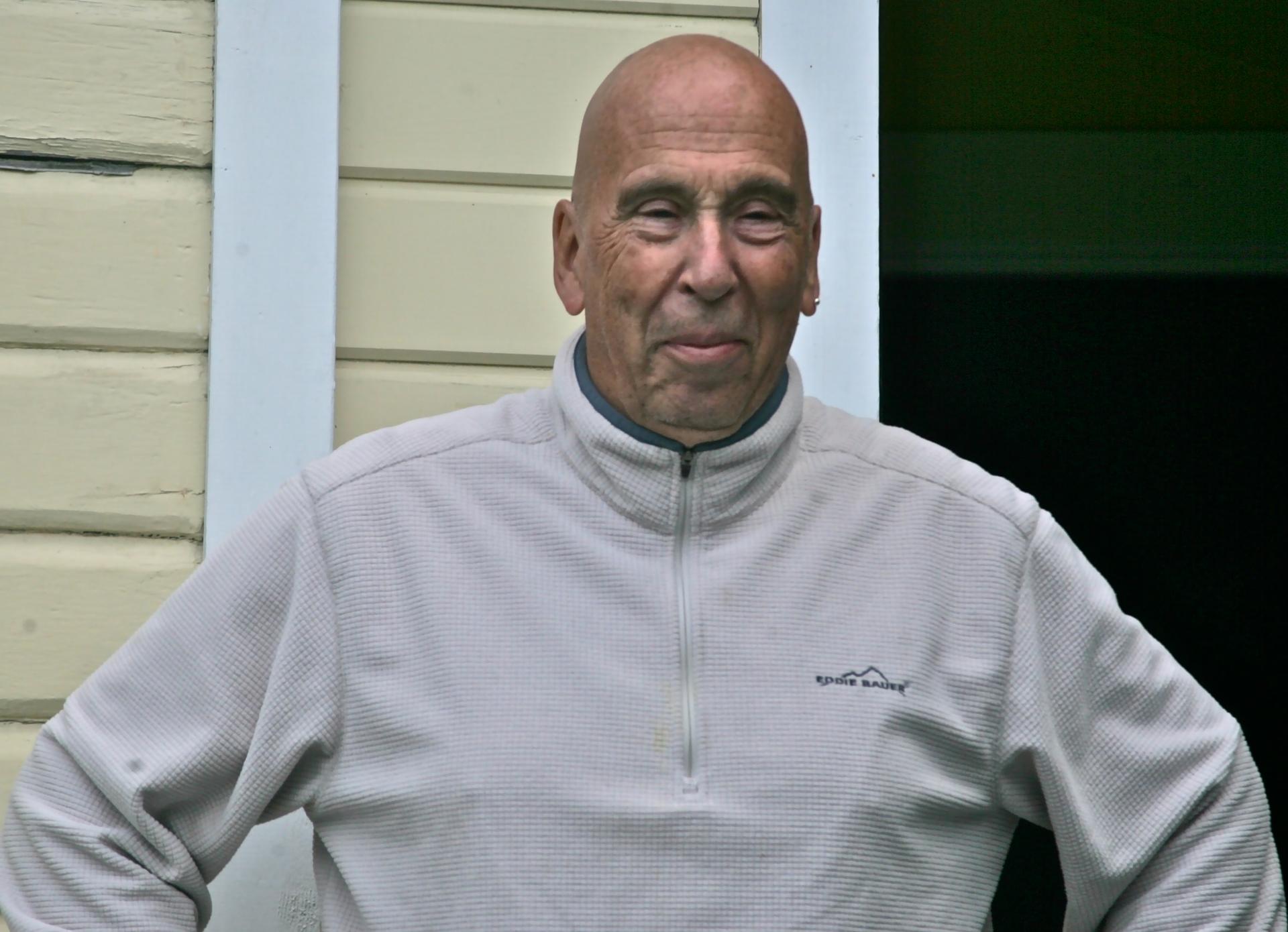

I met Peter during the decade he was teaching journalism at Shantou University, in southern China, when I was The World’s Beijing-based correspondent. Peter cut quite a figure for a 70-something-year-old guy — he’s now about 80 — bald, tall and lanky, hip, with a stud earring in one ear, a commanding voice, an infectious laugh, and a frank, funny, yet challenging way of teaching that endeared him to his Chinese students.

We sat down in Peter’s living room, looking out at Seattle drizzle over the waterfront, to talk about his 60 years in journalism.

MKM: When did you first start to see journalism as something you wanted to do?

PH: When I got my first job.” (Laughs) So I find myself in Alaska in 1958. Technically, I’m an announcer at a television station. Happens to be a CBS affiliate. And the man, one man, who was our news department, quit. So my boss came to me and said, ‘would you like to do news?’ I was 22 years old. What did I know? I said — ‘sure. Why not?’ That began a 60-year career.

MKM: So you stumbled into it. But why did you stick with it?

PH: If you like learning about new things, different things, and being forced to think about them, and then report them to other people in a coherent fashion — what could be more fun? And then — to be paid for it!

MK: What about the loftier goal of journalism, the role it plays in a democracy. Was that something that mattered to you at the time?

PH: Well, certainly not in an upfront, conscious way. … I guess part of it is, you’re always swimming against the current, as a journalist. You’re always fighting. God knows what — your own institution you may be fighting. It can be the government. It can be all kinds of things. But you’re always in opposition to something. Some people hate that about journalism. But you learn to live with it. And then you realize, as a result of doing that, the role you have in society. It’s not like you sit there and have great intellectual thoughts about it. It comes to you naturally.

MKM: So before you became a journalist, what was your exposure to journalism? What did you pay attention to as a kid, as a teenager, as a young adult, as a college student?

PH: Well, I’m an immigrant, born in Germany, with German parents. We escaped by the skin of our teeth, came to the United States. My parents were 40ish. I was 3 years old. The war was on. So, living in New York in that hotbed of immigration, my parents, quite naturally, spent a great deal of time absorbing as much information as they could about this new society they were in, and the war that was going on. Because they had left their lives behind. They were still reading German-language newspapers printed in New York, that kind of thing.

MKM: Were you bilingual as a kid?

PH: Yeah, yeah.

MKM: Are you still bilingual?

PH: Trilingual. I picked up French in the meantime.

MKM: Do you think that made a difference for you as you went forward as a kid, as a student, as a journalist, in recognizing that there’s always more than one way of looking at something?

PH: “Well, more important than just having the extra language, my mother had always wanted to learn French and never did. She was determined her son was going to learn French. So she sent me to a French school. That’s what did it. The French education system is so different from the American, because it does involve … critical thinking. You learn that as you put your thumb in your mouth in the French system (laughs), and you can’t get through it without it. It’s great training.”

MKM: Ok, so back to Alaska. You’re there, and you’re doing what kinds of stories?

PH: Those were the days when there were no satellites. Those were the days when there was no interconnection to the United States. That is, all of our programming from CBS, which is our network, was recorded here in Seattle, put on an airplane and flown to Alaska, and we put it on the air two weeks after the network put it on. So Christmas was always two weeks late.

MKM: And this was a year before Alaska became a state.

PH: That’s right. It was a year before Alaska became a state. At the time, I did the longest local newscast in all of television, 45 minutes long, all by myself.

MKM: How did you do that?

PH: I sometimes wonder. But the answer is fairly simple. We had one enormous studio. It was huge. Why? It had been a garage for the apartment building where we had our offices. They turned it into a huge television studio, which was endowed with one camera, one black-and-white camera.

I would go into the studio, where we had three sets set up, a news set, a weather set and a sports set. And I would position the camera to look at the news set, lock it in place, go to the desk, get the cue and I was on the air. When I was finished with whatever news segment that was, a commercial came from the control room. I got up, repositioned the camera, went to the sports set, pointed it at the sports set, locked in. And that’s how the newscast went, for 45 minutes — all by myself. And that was preceded by a local interview show – with, guess who? Me, interviewing somebody supposedly interesting for 15 minutes before I went on the air. So I did an hour of television, six nights a week. Sunday was off, technically. Sunday, I actually pulled a board shift. I was an engineer.

MKM: And this just seemed normal to you?

PH: Well, listen, you’re 22 years old, you’re just starting out. Everything you’re doing is brand spanking new. I was having the time of my life.

So, Peter spends three years doing all this in Alaska. He gets a CBS fellowship to study anything he wants, except journalism, at Columbia University — which happens to be his alma mater for his bachelor’s and master’s degrees. So that puts him back in New York. He applies for and gets a job with the CBS national network. He starts on the overnight assignment desk. It’s 1961.

MKM: So there you are at what was to become, arguably the most influential news organization in the United States in the ‘60s, in a decade that was quite extraordinary for the country.

PH: Right after I got there, CBS News had a new president, by the name of Dick Salant. To all of our horrors, he was a lawyer. And we thought the world had come to an end. A lawyer was going to run CBS News.

Well, he was there for 17 years, and after his first year, all of us would have died for him. He turned out to be the man who gave the foundation to what CBS News was all about to all its audiences, why it became as influential as it did. He, coming into that organization, immediately started to plan an expansion of the Evening News, which in those days was 15 minutes.

But — the day President Kennedy was assassinated, the world changed. The world of television changed. The world of news changed. The expectations of the public changed. And I suppose you could draw a line saying, it said something about the future of print, at that point.

MKM: Why is that?

PH: Because, suddenly, a medium that only people who had an intense interest in news paid any attention to — and even then, it was disappointing, because the news we did in 15 minutes was a bad joke, in terms of our capabilities. It wasn’t serious, not serious in the sense that we didn’t have serious stories, but compared to The New York Times or The Washington Post or any other newspaper, even a worse newspaper, we were nothing.

Suddenly, with the assassination of President Kennedy, we, and NBC, too — ABC wasn’t a big factor in those days — were on the air for four-and-a-half days, nonstop. Television had never done that with anything. The public came to expect this of television, that when events occurred, they wanted to see it on the TV set. Now, nobody even thinks about that. You don’t even go to your TV set. You go to your smartphone, you go click, and you’re watching, anywhere in the world.

MKM: Now it’s perhaps gone a little too far, where you have six hours of coverage of a storm. It’s like — OK, it’s still raining. We get it.

PH: But any time in those six hours you want to check in on the storm, it’s there. That’s the other side of it.

MKM: But there are a lot of other things going on in the world, too.

PH: And they’re available, too.

MKM: Not necessarily. If you’re throwing all your resources at the storm and you’re not paying attention to other (things).

PH: But you’re not.

MKM: A lot of news organizations now do that. CNN, Fox, when they decide to go full-bore on one story, you’re not hearing about other things that are happening.

PH: Other organizations we’re not so familiar with do it. The point is, there’s a proliferation of sources. Yes, in terms of cable which — by the way — itself is dying, because of the Internet — cable has a finite number of news sources. And you’re right. They pounce, all on the same story, very often showing the same pictures, all that sort of thing. It’s utter nonsense. Ridiculous.

But it’s not that you don’t have a choice. You can go click off on them, and go to other sources, and get what you want, from angles you never had before. I mean, from foreign sources. So what you’re saying is absolutely right. But it’s not that you’re cut off from everything else. It’s the other things. Because if they’re going to be so idiotic, all covering the same thing — and we used to do that too, on the network news. If you tuned into NBC, or CBS — we were the dominant networks at the time — almost every night, our lead stories were the same. And if you take a step back, you look at that and say, ‘Come on.’

Our competitive thing was, if they lead with this, and we don’t lead with this, we must be wrong, or they must be wrong by not leading with what we did.

MKM: So back to your time at CBS. So the Kennedy assassination changed how people look at television news. You also shifted in your career. You became a writer for Walter Cronkite.

So I started out — he took over the old 15-minute newscast … and I was writing for him for the half hour, at that point, because we had a test team. A lot of people were saying — can you believe it? — "how can you do a half hour of news? How are you going to fill it? What are you going to put in it?" And we were part of it. We said to ourselves, ‘How can we fill a half hour of news?' Which in reality is 22 minutes, by the time you pull the commercials out.

MKM: And you’d been filling 45 minutes of news all by yourself.

PH: And I never put those two things together. It was the pressure of, suddenly we had a national audience, and the idea of not having enough news to fill those 22 minutes, the idea that we might come to the end and not have enough? It was a frightening thought. A really frightening thought.

MKM: So what was Walter Cronkite like as a boss?

PH: Part of his contract that he had with CBS News was that his title on the broadcast was not anchorman. It was managing editor. Old newspaper term, right? And the managing editor of a newspaper, in those days, was the super boss. Nobody interfered with his or her — and there were hardly any hers in those days — his news judgment. And that’s what he demanded. He demanded that kind of editorial control.

So he set the news agenda. We all offered ideas, we made offers to him. But he did the picking and choosing of what the news agenda was going to be that day. That was number one. Number two was, writing for Walter was the experience of — any wire service reporter knows this. It meant, write tight, and write fast. But writing tight for Walter meant, he averaged six minutes of the 22 himself. On a good day, it was maybe seven or eight, on a bad day it was maybe four, but the average was six. In those six minutes, he tried to get as much news in as possible, which included the introduction to the longer correspondent segments. So the idea was, put as much information as possible into as few words as possible, and still make it coherent.

And his talent was to take a news story you wrote in maybe 15 or 20 seconds, pull five seconds out and not lose any meaning. He was very good at that. That’s a real skill.

MKM: So you kind of learn to write news in Haiku.

PH: That’s right. Exactly. That was his thing.

MKM: Now, at the time you were working with him, there was a survey that came out that showed that most Americans were getting most of their news — all of their news — from television broadcast news.

PH: That was later on. That was during the Vietnam War; 85 percent of the American public was getting all of their news from ABC, CBS or NBC. And Walter was appalled. And he called us all in, and he said, "Look, we have a new job. And the job is, we have to get more news into the time we have." And that meant writing even tighter.

MKM: Do you think the ‘60s were kind of exceptional, in terms of how people viewed journalism and the role of journalism, because of what was happening in society, because of the reaction to the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement, the environmental movement, the feminist movement? There was just a lot going on, and people started to pay more attention.

PH: The civil rights movement — that was the biggest thing. That was a revolution. No two ways about it. That was a major revolution in the United States. And very much like the Kennedy assassination, we brought that home to living rooms. And people were looking at things, and saying to themselves, "This is the United States? Things like this are going on in this country?" By then, I had become Midwest bureau chief. I spent the entire time in the South, covering the movement, being a field producer.

MKM: When you look at this particular story (race relations and civil rights) come around this time, what strikes you about the way it’s being covered?

PH: Part of the answer, I think, is that Black Lives Matter has the capability to do things that they could not have done 20 years ago, simply because they have outlets to take action, to make themselves heard, to get their message out, that were not available to them before. And I think probably to a certain extent to their own surprise, they’ve taken root a lot faster than they might have in the past, when they might not have taken root at all. I mean, there were organizations 10 or 15 years ago that were doing exactly the same thing, and were frustrated out of their minds, because nobody was listening.

MKM: So you covered the civil rights movement. You then covered the Vietnam War.

PH: Right.

MKM: What did covering the Vietnam War teach you or show you or reveal to you about what information was getting to the American public, and what was being kept from them, by the government, what you as a journalist needed to do to bridge the gap?

PH: When I went to Vietnam as CBS bureau chief, we had access to everything and anything we wanted. Yes, there was the official version of the war. Every afternoon at 5 o’clock, the military did a briefing, which got to be called the 5’o clock Follies, because it was. It was a folly. But we all dutifully went, and reported what the government was saying. But the entire rest of the time, we were out in the field, being taken out in the field and protected, by the American military, to report exactly the opposite of what the government was reporting. Now that had never happened before. World War II had censorship. And we had none. Nobody ever interfered with anything we did, or even, in my experience, even tried.

MKM: Why do you think that was? What made Vietnam an exception?

PH: Naïveté. Simple as that.

MKM: They thought you as journalists would be on their side?

PH: Not necessarily on their side. But they thought we would do a job they could live with. And I think this — maybe naïveté is going too far.

I think this was the classic, the Washington view of the war vs. the Vietnam view of the war. They had put command in place that basically agreed with Washington. What we were doing, how we were doing it, the values of what we were doing. We were trying to protect the South Vietnamese way of life, and democracy, and all the good things.

The reality on the ground was totally different. And there were many, many, in the American military, and in the American civilian establishment, who were sending that message back to Washington. But they were deaf. They didn’t want to hear it. And when you don’t want to hear it, you don’t believe it when it’s being said to you, and you’ve got all of your own people telling you the opposite.

Things are going fine. Just send me more troops, and we’ll win this thing. And that kept going. That vicious circle kept going. And then, there was this nattering crowd of journalists, which by the way turned out to be huge, and this was worldwide. Other countries were way ahead of the United States in understanding the idiocy of that war. That’s another part that I think Americans don’t realize, that we should have done a better job of reporting that.

MKM: So when you were there, how many people were watching the evening news on CBS?

PH: I know the audience for CBS News in those days was larger than the audience today for all three networks combined.

PH: Huge! To the American public, this was being pounded daily into their heads, very much as with the civil rights movement. What the hell was going on here? Somebody had to do something about this.

MKM: There was a moment when your former boss, Walter Cronkite, kind of stunned the American public with what he had to say about the Vietnam War.

PH: And if you go back and read what people, and he, considered an editorial, it’s so mild, you’d sort of smile today, compared to what you’d watch on Fox News any night of the week. He, being who he was, said, "Listen, I have to get out there and look at this. We’re reporting this every day. I haven’t been there. I want to have a chance to have a look at this."

And he was, at that point, the most trusted man in America, the biggest star there was. And you can imagine how a man like that gets treated. The American military, certainly in Washington, saw this as the golden opportunity. And they laid out the red carpet and made anything available to him that he wanted. And he fought very hard to do exactly the opposite of what they wanted him to do, because they wanted him to talk only to the top military commanders, and hear the story that they wanted to put out.

So Walter worked with — I wasn’t there at the time — he worked with the correspondents and producers who were there at the time, and got what he needed. And he got what he needed within 24 hours. He went out into the field, talked to troops on the ground, and came back in a major depression.

By the time he got back to New York, which I think was a week or 10 days later, he had already started wrestling with this idea of his. Those of us who worked with him never knew what his political leanings might even be. We had him everywhere from far right to far left. So in that atmosphere, you can imagine what it took for this man to get on the air and give his opinion of what this war was about. That was a total antithesis from his view of what the role of the anchorman was.

MKM: What do you remember of the public reaction to that?

PH: Oh, it was about a nine earthquake.

MKM: Were people calling him unpatriotic?

PH: Remember what Lyndon Johnson said? "We lost the war. We lost Cronkite.” And he was right.

Now, did that single event do it? No. But it was that important, certainly to the CBS News audience that heard it that night. It was something that they had never expected to hear from this guy who they had put all their trust in. It was on everybody’s lips. It got talked about. The newspapers helped enormously. It was headline news in newspapers all over the United States. And of course, it gave a shot to the antiwar movement.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DNn4w-ud-TyE

MKM: For a span of time, and you were there for that whole time, CBS, and the networks more generally, had this outsized influence. They had extraordinary resources. Do you think that was healthy? Do you think that was a good way of providing journalism for a population? Or do you look at the explosion of sources now, and think that’s better serving the public?

PH: For our egos, it was much better the other way. It really was. We reveled in it. And we had no perspective. We didn’t ask ourselves the questions we should have been asking. And there’s no question, this is a far better world. The challenges are much greater, for you the audience. But in terms of the news flow, the availability of choice, there’s no comparison. This is an infinitely better world. It’s a more challenging world.”

MKM: What about the level of rigor that journalists bring to what they’re doing? When you look at what’s out there now, and you deconstruct the stories you’re hearing, or reading or seeing, how does it compare with what you were doing back in the ‘60s and ‘70s?”

PH: Well, we were our own rigor. We had to come up with that. That’s why I keep coming back to someone like Cronkite, or Dick Salant. They were so rigorous on us. They gave us the culture that we lived in. And that’s the reason CBS News was successful, and it wasn’t any less successful at NBC. NBC had their own rigor, too. They didn’t quite have the strong personalities we had, but they were damned good at what they were doing, and they very often beat us, too.

Now the same thing was true in print. The editors at the New York Times, and the Washington Post and the great papers of the day had that weight of responsibility on their shoulders. They knew they were the guardians of good journalism. Now, the world has changed.

Now, my view of it is, the responsibility has now fallen on the shoulders of the users of the information. You have to do the work that the old editors did, which means there are people out there — I mean, jobs in journalism have exploded. There are more jobs in journalism now than ever before in the history of journalism. Some of them pay unbelievably badly, some pay none at all, others pay increasingly well. … That’s the economics of journalism.

MKM: If they pay none at all, is that a job?

PH: Sure it is. Of course it is. Because, if you’re in love with journalism — there are people in journalism who say, "don’t ever let them know, but if they didn’t pay me, I’d pay to do the job." It really is that good a job.

MKM: Well, I wouldn’t argue with that, except — I agree it’s a great job. But how do you create a generation of journalists who can mature as journalists and use the experience that they’ve gained along the way, if they can’t pay the rent?

PH: I think the way you become a journalist, and the way you learn in journalism has also changed. I’m of the school of thought that says anyone can be a journalist. It’s not an occupation you need an education for. What you need is a brain and judgment, and all the things that go into good journalism. And that can come from anybody.

MKM: So you have all these people — anyone, really — if they want to write something and put it online, or podcast, or whatever, they can do it. And you say users are now the ones who have to bring the rigor to the process of figuring out what’s worth paying attention to: "How much do I trust this source, how do I know this is accurate?" How do you think users are doing?

PH: Very badly. Because they’re falling into a terrible trap, which is our natural penchant to want to be in an echo chamber, and hear ourselves coming back at us, and watching, listening to and reading things that agree with us, and not taking the trouble to do the opposite, and look for stuff that’s uncomfortable. That’s a human failing. It has a long history. It’s not about to change. That’s why an organization like Fox seems to be as successful as it is. It isn’t. If you look at the Fox audience, it’s infinitesimal.

MKM: It’s like 2 million.

PH: Yeah, day in day out, they’re under 1 million. The old story is, there are fewer people watching Fox or CNN during normal daytime hours, than watch a single newscast in New York City on one television station. But their ability to make noise is incredible. And the genius of Fox is the genius of the man who created it, who has created the impression that Fox dominates the world.

MKM: Well, it’s also amplified because other media pick up on what Fox says and does, or what CNN says and does.

PH: This is the failing, in part, of traditional journalism. Because we still have a tendency to be lemmings, and follow each other. And what has just passed, in the most recent debate with the Republicans? The next day — in reading what I normally read, which is a number of the great traditional newspapers, and other sources that are more remote — they’re all over the story, saying the same thing over and over, as if there’s nothing else going on in the world. It’s mind-boggling. It’s frustrating as hell.

MKM: Well, as if there’s nothing else going on in the world, and also, in watching the debate, there was no fact-checking along the way, there was no pushback along the lines of, "You just said something that’s completely untrue." So it’s left to stand, and people who are watching the debate, who don’t have any context, who don’t have the time to read widely, and decide for themselves what is actually the case, they just take it on face value.

PH: Yeah, but the answer to that from them would be, the standards of traditional journalism.

MKM: We report, you decide.

PH: That’s right. Not only you decide, but we don’t get involved.

MKM: But those weren’t the standards before. It was that there was an expectation — certainly when I was in journalism school in the early ‘80s — we were told; "Your job is, you report the heck out of the story, and you get as close to the truth as you can. And you fact-check everything. That’s your job."

PH: But we’re talking about live television. A debate is live television. And I would agree with you in this sense. The moderators of those debates know enough, or they should know enough. And where they know better, they should be jumping in.

MKM: Don’t you think viewers, and consumers of news — viewers, readers, listeners — want journalists to say, "look, we know this is true."

PH: Most of the audience wants to hear what they want to hear, not what you’re telling them, especially if what you’re telling them is against their grain.

MKM: So then, what’s the role of a journalist? It’s not a popularity contest, right?

PH: No. It’s to do what we’ve always done. Get as close to what happened as what did happen. And — we’re not very good at it. We never have been. And we never will be, certainly on a day-in, day-out basis.

MKM: Well, what happened, what it means, what are the underlying issues, what are the underlying trends.

PH: Well, that’s a leap. That’s a leap.

MKM: But if you don’t have the context, what happened is just a data point.

PH: Yeah, but — it’s one thing to report what you’re actually seeing, and what you’re actually hearing, which by the way is usually flawed, because someone else is seeing something else, and hearing something else, from a different angle. You’re both right. But you’re both wrong. So you’ve got that aspect of journalism. Then you’ve got the other aspect, which is analysis, context, what does this mean? Why is this going on? You have your opinion. I have my opinion. That’s why we have commentary pages and editorial pages, and why we, hopefully, separate things, and get very careful about what we put in the news story.

MKM: I think it’s different saying "this is good or bad," versus "here is part of what’s going on," which is analysis, which is part of what goes in the news hole.

PH: You and I might have some arguments about that. See, I would say, "Yes, it needs to be there, but in a separate box."

MKM: So when you read The Economist, The Economist is all analysis.

PH: Yes. I know that. And this goes back to another principle we haven’t talked about, which is, what’s permissible and what’s not permissible in journalism. And my answer to that question is — do anything you want, just tell me what you’re doing. And then I will have the context that I need.

MKM: So this podcast is called “Whose Century Is It?” You’ve spent well over half a century in journalism, both as a practitioner and as a teacher. As you’re looking at where we are now and how we move ahead, as a society, let’s say specifically in the United States, you’ve said it’s never been a better time in terms of what’s available. But in terms of the role that journalism plays in the United States, in this democracy, how are you feeling?

PH: Just as optimistic.

MKM: Just as optimistic.

PH: I think what is the opportunity that has not existed before is … there are now so many ways of doing journalism, and ways of getting that out of your system. Whether you’re doing it as an avocation, or as your life’s work, that only grows.

Don’t expect to have 3 million people listening to you, watching you. You’re going to have to be satisfied with a much smaller audience. You may go viral. You may do something that suddenly has 5 million people. And it will last 24 hours. And you’ll be long forgotten, as the event that did it, or the video that you suddenly got, or that kind of thing.

But the world of information has only begun to be touched. We are only in the baby steps. And — I could project in 100 different directions, where this could possibly go. The only one I have any confidence in is, "more, more, more." And that presents its own challenges.

MKM: Is there anything where you look ahead, and you think, "this could really be a problem, if it continues the way it’s going"?

PH: Well, first of all, it isn’t going to change. It’s only going to get more of what it is. So — we’re not going to go back to another time. We’re going to go forward to something else.

The danger is already there, and it’s what we’ve spent some time talking about, which is — the ability to do dirty work has also expanded, enormously. You can make more mischief now, faster, than ever before in the history of mankind.

And because, unfortunately, viewers, listeners and so forth, are as lazy as they ever were, you can get away with it. There’s a limited amount of time. And I think an organization like Wikipedia has taught us, since anyone can go in there and add anything to a Wikipedia piece, a lot of people have tried to put in bad information. It doesn’t last more than a few seconds, before somebody pounces on it and corrects it. And the same thing is true of other things on the web that are in any way accessible. You can make mischief, and you’ll get caught out.

A good example at CBS: Dan Rather’s career ended because of people who picked apart a story that he and his producer put on television, before he even got off the air. It was on the air, when they came on and questioned the source material that was used, and that turned out to be flawed, and where the whole story came apart. And the story was — Rather retired, and his producer was fired.

MKM: So, there are shoals to navigate, for journalists. But overall, it’s interesting that you’re feeling very positive, very optimistic, about the future.

PH: More than I’ve ever felt.

*****

I love Peter’s optimism. He seems to delight in the endless exploration of news sources the Internet now offers — and he’s sure more adroit at finding them than any other 80-year-old I know. It’s also impressive how comfortable he is rolling with the changes in our field, which have knocked many a journalist half his age off-balance.

Then again, Peter did have a long stretch of getting paid well to do what he loves. I wonder what it will be like for the generation just coming into journalism now.

As to our conversation on context and analysis — I think it reflects a generational shift. In Peter’s heyday, journalists thought of themselves as objective. Since then — it’s more common to accept that everyone brings their own lens and experience to what they do, and should be aware of that, and should try to correct for it — go out of their way to test their assumptions, and listen to other perspectives. After all, there are so many subjective layers in doing a story –— what story? From what angle? Doing what research? Using which bits of that research? Quoting whom, and why, and why not others? And that’s not even getting in to the placement the story gets when it’s published or posted or broadcast.

So I agree with Peter — it’s an incredible thing that so many more voices can now tell their own stories, their own way. As he said, it’s a challenge to figure out who’s worth listening to, whom to trust — but it can be done.

It is being done. Another generational shift is underway. I wonder what I’ll be saying about the state of journalism when I’m Peter’s age. I can only aspire to being half as hip, and as comfortable with riding the wave of change. Meanwhile, I’m grateful to him, and his generation of journalists, for the example they set, and the inspiration they gave kids like me, way back when, watching Walter Cronkite and 60 Minutes and imagining a life in journalism.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?