This Jewish couple survived the Holocaust hidden behind a church organ. Their daughter — also in hiding — had no idea.

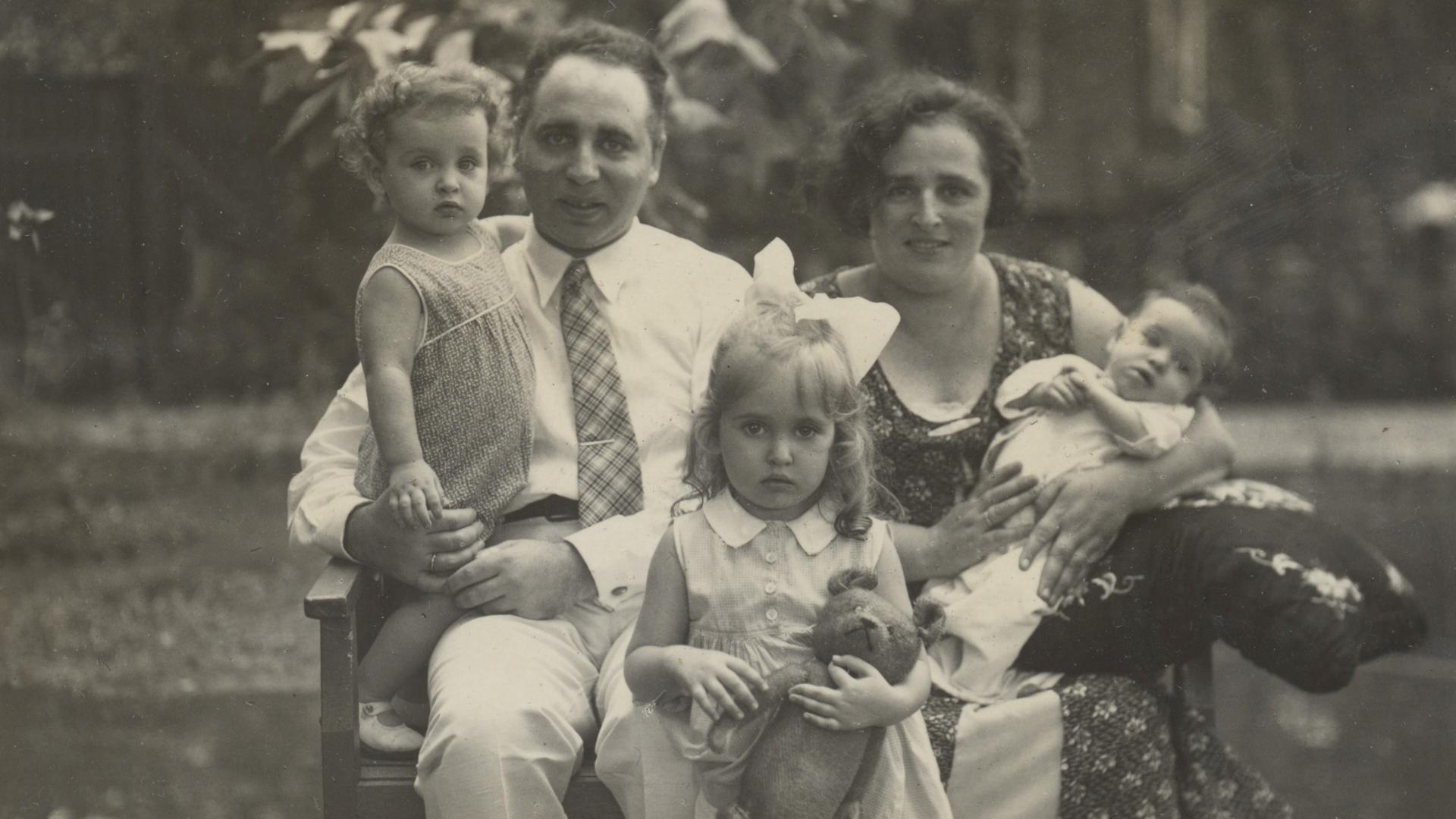

(Center Front) Mirjam Geismar de Zoete; (Center Left) father Chaim de Zoete, with daughter Judith; (Center Right) mother Sophia de Zoete, with daughter Hadassah.

Watching refugees escape Syria and Iraq has been really difficult for many people. I know it has been for me. Just imagine what it's like for them.

For one thing, the sheer number of people is numbing.

So are the constant stories of children in trouble. Children dying en route to Europe. Children who lose their parents and then end up alone and scared.

Mirjam Geismar knows what it's like to be a powerless child. She was a young Jewish girl in World War II Holland. I met Mirjam — and her daughter Daphne Geismar — in New Haven, Connecticut, where they live. About 70 years ago, Mirjam's own story of suffering ended when the war ended.

For nearly three years though, she didn't see her parents. Didn't know where they were. And didn't know if she would ever see them again, or what the future held.

Curiously, before Mirjam was separated from her parents during the war, she was seeing into the future — in her dreams. She had one recurring nightmare that a German shepherd — a dog once associated with the Nazis — was chasing her.

She also had another recurring nightmare. It went like this.

"We were all standing somewhere, looking at a clock," Mirjam recalls. "And they said, well if the clock stops at 12, that's when the war will start. And we were all looking, and it stopped."

On August 19, 1942, the day of her parents' anniversary, Mirjam came home from school.

"I went to my bedroom, and I saw my parents coming, and they said we have to tell you something. And then they said, it's gotten too dangerous. The Germans are somehow going to find us, we have to find hiding places. And we found one for you," she says.

At the age of 11, Mirjam got on her push scooter, and left her parents and her two sisters. The first family she stayed with she knew.

"I had braids. And before I was sent to this first family — on my scooter — they changed the name from Mirjam to Manya, because Mirjam was so obviously Jewish. And they cut off my braids — I had long braids — because they supposedly made me look more Jewish," Mirjam says.

Later, she was transferred to another home — people she didn't know — and then a third where she stayed for the rest of the war. At the third hiding place, the full extent of the fear she and the people hiding her were feeling was undeniable.

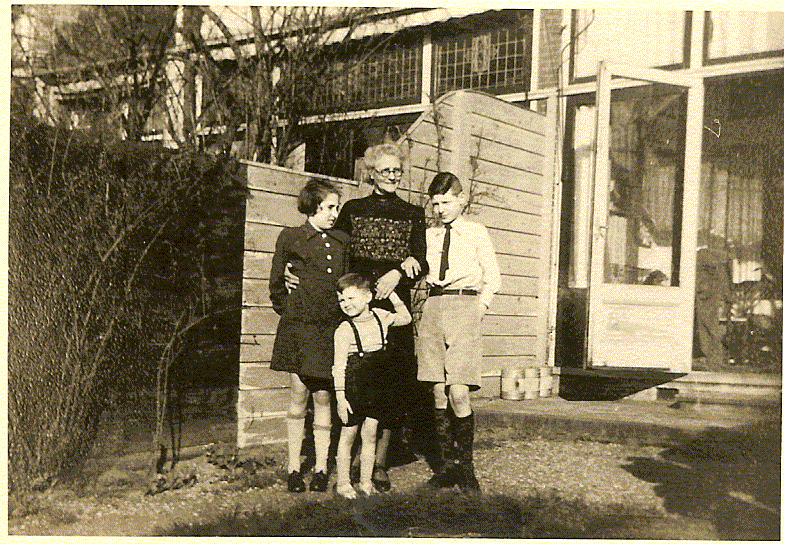

Home number three belonged to Tante Nel, a single mother. She had a daughter of her own. And she was already harboring a Jewish boy. Tante Nel wanted to help. She also needed some income and hiding Jewish kids would bring her some money.

But near the end of the war, food was so scarce that you needed a relative fortune just to feed a small family. Tante Nel resorted to things like mashed tulip bulbs mixed with flour to keep herself and her charges from starving.

As scary and untethered as daily life was for Mirjam, it all became kind of routine.

Mirjam says they slept in a hiding place at night under the kitchen floor only accessable through a trap door.

"We had a potty, so just in case we had to go to the bathroom," she says. "We had been asked to keep it in as much as possible."

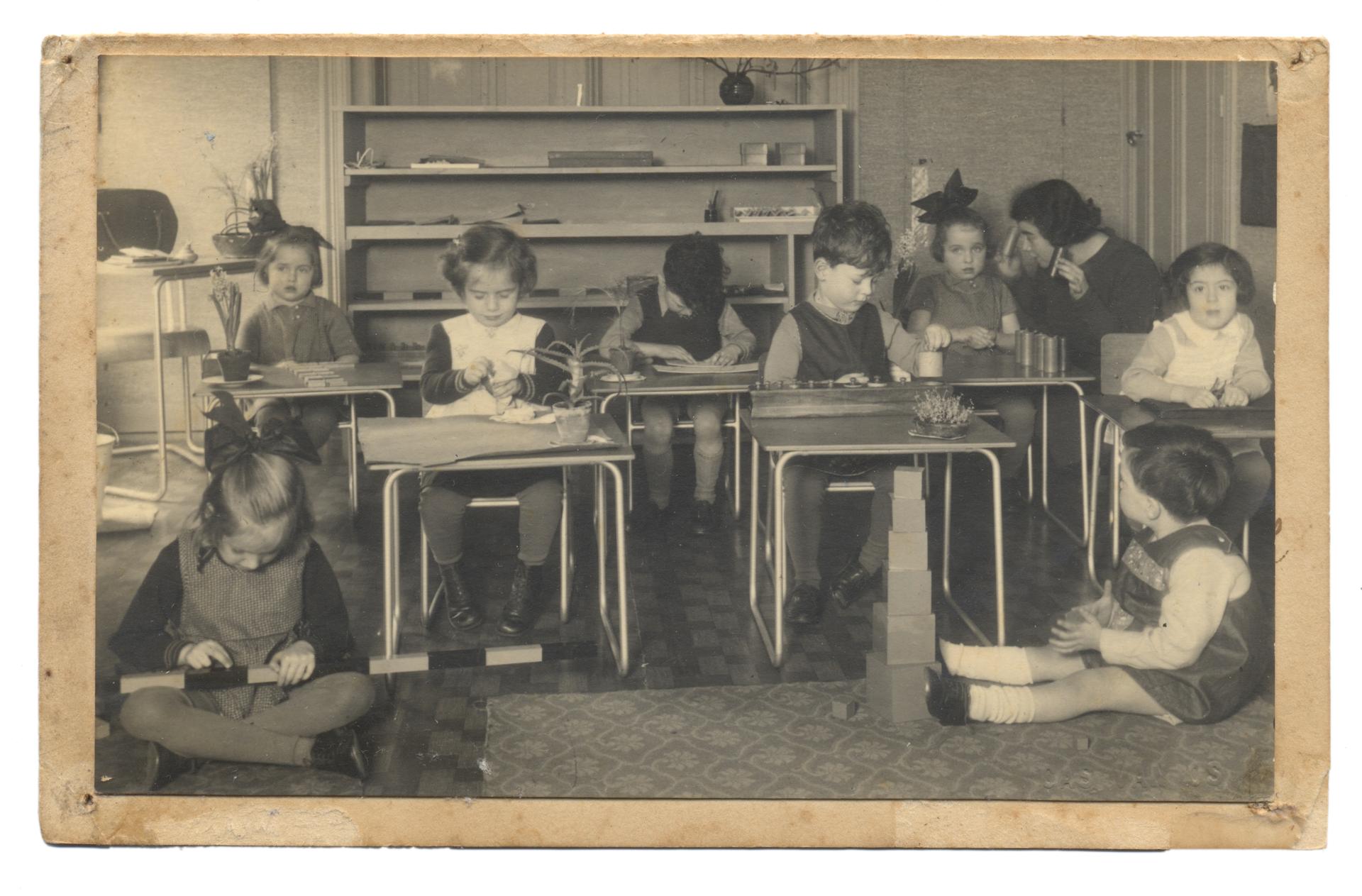

There were some books in Dutch that Mirjam read over and over. "Winnie the Pooh," "Uncle Tom's Cabin." Occasionally, a teacher would slip by the house and go over reading, writing and arithmetic with the kids. Strange knocks on the door though were rarely answered.

Mirjam knew her parents were still alive. But she didn't know where they were.

Her parents had sorted out hiding places for their three girls. But they struggled to find shelter for themselves

"They went house to house like begging, where they knew somebody. Ended up at his sister's house who was married to a non-Jew. His sister was a teacher. So was her husband. They didn't have any children. They went there to beg, ask if they could stay there for awhile. And his sister said 'no.'"

Before the war, Mirjam's father had held an important job as the chief pharmacist of the city of Rotterdam. He knew people. But not even his own sister would risk hiding him. There was another option.

Mirjam's parents ended up being sheltered in a church.

"The pharmacist in Rotterdam who helped my father with medication, also found out about the church," Mirjam says.

That pharmacist introduced them to the minister of the Breeplein church in Rotterdam. And he agreed to take them in. The church is still there today, with a plaque out front explaining its role hiding Jews during the war.

I asked Mirjam if her parents were physically in the church? "In the roof," she says.

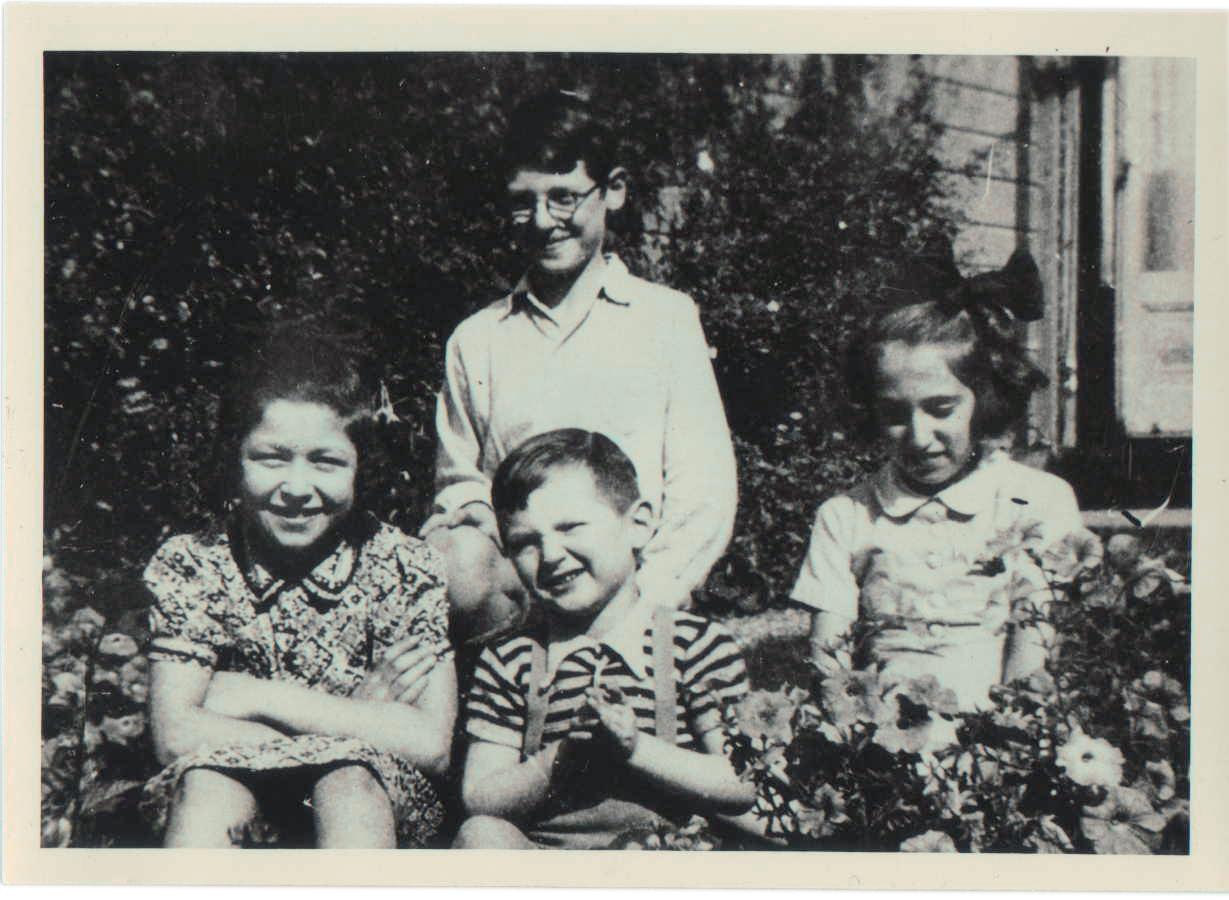

Mirjam's daughter Daphne has become kind of the keeper of her parents' and grandparents' history. She knows their story well.

"The minister went to the caretaker of the church, and said 'I would like you to create a place for this Jewish couple to hide,'" Daphne says. "And the caretaker said, 'well, I never told you this but there's another Jewish family that's been hiding in the attic for a year already.' So they made a second hiding place, so there were mirror images on either side of the organ pipes."

Two and a half years living behind a church organ. That's bound to have some consequences.

"That's why my parents hated organ music after the war," Mirjam says.

They hated organ music, but they survived. On a personal level, though, the conditions they found in that church crawl space completely re-ordered their lives.

"They had to lay in bed the whole daytime, because people who visit in the church could hear them walking if they would be," Mirjam says. "And they slept sometimes for 24 hours they were in that bed. Well, if you have a good marriage it goes really well maybe. If it's an in-between marriage, it's not the best, but if you have a trerrible marriage it's murder."

I asked her what her parent's marriage was like?

"Good," she says. "My mother was very vivacious. And my father was philosophical. He kept her happy with sleeping pills. And after the war she was addicted to them. But for a year or two after the war, she was like someone who was drunk all the time."

The pills kept Mirjam's fidgeting mother quiet in their hiding place. Silence was crucial. Months before the end of the war, there was one close-call where noise would have given Mirjam's parents away to the Nazis.

"They were looking for weapons," Mirjam says. "Somebody had told them that there were weapons hidden in the church."

Mirjam's daughter, Daphne, pickes up the story, saying that her grandmother was asleep and right below the attic was another little room behind the organ pipes, so nobody came up there and that's often where my grandfather would go to read.

"He was there (in the room) and he suddenly heard this commotion that was actually the other family hiding on the other side of the organ pipes," Daphne says. "And they were saying 'Quick, quick, get into your hiding places.' So, my grandfather looked out into the nave of the church and he saw the Dutch Nazi police searching the church. He knew he had to get into his space very quickly and without anybody hearing him. There was a ladder and he crawled up into the space and then he would throw the ladder up and catch it.

"He couldn't pull it up because it would grate along the side and make too much noise. He got the ladder up, closed the trap door and was very happy to see that my grandmother was sleeping and she would be quite. The SS did come up to the space right below where he was and as they were there he saw this spoon from lunch teetering on the edge of the stones and could have fallen or not. It happened not to have fallen."

Daphne says her grandfrather heard them searching around in the pipes of the organ, and then they left.

It's just one of many incredible stories that emerged from war. The stories of the ones who survived. By sheer luck in many cases. Many Jews thought that all they had to do was hide, be quiet, and things would be fine once the war was over. Mirjam's family did.

"We just said, we'll be quiet, we'll survive, and we'll come nicely together," Mirjam says. "And somehow it worked for me. But it didn't work for many, many people. Many more."

So why do we tell these stories? I asked Mirjam that. And her answer, basically: Because stories are the only thing the survivors have.

"That's the only you've got to fight it back," she says. "What else is to do? You feel you have to do something. So you tell the story, maybe. If it helps one person, it's worth it, I suppose. Especially if it's your child.

And so Mirjam told Daphne, her daughter. And Daphne tells her daughter. And they tell me. And I tell you.

When the war ended, Mirjam and her two sisters were brought out of their hiding places and taken to the church in Rotterdam.

Her family did come back together. Sheer luck. But somewhere in that luck lies some hope.

Mirjam's parents couldn't tolerate organ music again. But her father never lost his taste for Mozart.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?