India brings back ancient wisdom to fight its modern environmental problems

Across India, farmers and other citizens are taking water management into their own hands. Rajendra Singh, known as the "rainman of Rajasthan," stands in front of a small check dam or johad. Check dams help slow water run-off from monsoon rains, allowing it to filter into the ground to refill wells and aquifers.

When it comes to global efforts to fight climate change, India quickly becomes Exhibit A. Like other developing countries, it seems stuck in a zero-sum game where it must choose between fast economic growth to bring its people out of poverty or protecting the environment.

India is the world’s third largest greenhouse gas polluter. It struggles with a lack of clean water and impoverished farmlands. And while it plans to vastly increase renewable energy use and has committed to emissions reductions for the Paris climate conference, it also plans to increase its coal-fired and nuclear power capacity.

India’s climate negotiators argue that, given how modest its emissions are per person, the country both needs and has the right to use fossil fuels to spur growth.

“India has huge challenges in front of it and Prime Minister Modi is really pushing development,” says investigative journalist Meera Subramanian. “He won a landslide election last year on the platform of development, [but] I feel like India has a huge question before it of how it is going to develop.”

That's because environmental problems, in some cases, can actually interfere with development. Subramanian criss-crossed India looking at that tension and at solutions, which she describes in her new book, A River Runs Again.

“It is easy to be overwhelmed by something as big as the state of the environment and the natural world in a place like India, and so I wanted to make it accessible to people,” Subramanian says. “I wanted to write stories about what people are doing on the ground in India today, right now.”

Subramanian took aim at the legacy of the Green Revolution, which changed farming practices in India and other countries around the world in the 1950s and 60s.

The Green Revolution was hailed as a huge success. Its promotion of better seeds and use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides did increase food production dramatically. But on many levels, Subramanian contends, it didn't succeed. Fifty or so years on, “we’re finding that soil is depleted, water has run out, food has chemicals in it that are changing our bodies and the environment, [chemicals are] changing the quality of the water that runs off of farms — and all of those things are having huge impacts,” according to the investigative journalist.

The Green Revolution is not just about farming techniques; it is an entire economic system, according to Subramanian. “I met one farmer in Punjab who just felt it was [like paying] constant admission fees — and every time you paid one ticket, it would work for a while and then the magic seed suddenly didn't work any more and a new pest had come and you had to get a new pesticide. He just felt like he was on this hamster wheel that he couldn't get off.”

But this farmer did get off. He decided to go back to how his father farmed before all the chemicals were given out. Many other farmers Subramanian met were also starting to farm some of their acres organically, while continuing to farm the rest using chemicals to get higher yields.

Guess which crops they were choosing to feed themselves and their families? Subramanian says, “It was the organic and then the rest of it would go to market.”

“A lot of the science says that switching to organic is not going to get you the yields, but the seeds cost less, the inputs are less, soil becomes alive again, it holds water better, it decreases erosion [and] it's an amazing carbon storehouse — so all these factors come together,” she explains.

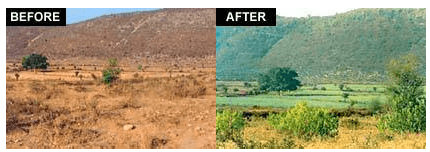

When it comes to water use, Subramanian also documented a return to older practices. In the semi-arid region of Rajasthan, wells and aquifers had become depleted due to a growing population and intensive agriculture. People were leaving because there was no way to work the land or maintain livestock.

Then, led by the efforts of Rajendra Singh, known as the Rainman of Rajasthan, they started building small-scale dams called johads that capture the rains when they come. “Just that small action, helping the water pause so that it doesn't run off, cause erosion and disappear, allows it to percolate down into the aquifer, constantly replenishing the system,” Subramanian explains. “Wells that had gone dry began to spring back to life.”

Systems like these were in place in some version all across ancient Asia and China, Subramanian says, but they had been forsaken as countries started using big dams and farmers started believing that the government would provide the necessary water; people stopped taking care of their own plots of land the way they used to.

Now they are discovering that reinvesting in their local landscapes and taking part in the management of them in a really positive way can make a big difference, she says.

“I think that's where the most hope comes for India, recapturing a lot of the ancient knowledge and pairing it with all of the things that we now know."

There are, of course, valuable high-tech approaches to agriculture and water management; smart grids and other techniques can improve energy usage, which is a huge part of the crisis India is facing right now. These have nothing to do with traditional knowledge, Subramanian says, but “combining the best of the old and the best of the new could really blaze a new path forward.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.