China helps clear a path to a climate agreement in Paris

Windmills in China. China and the US reached an agreement in which the Chinese announced the launch of a national cap and trade program.

China, the biggest emitter of global warming gases, announced it would soon implement a nationwide cap-and-trade program, and partner with the US, the world’s second biggest emitter, on other ways to reduce emissions.

According to Jennifer Morgan, the director of the Climate Change Program at the World Resources Institute, the new commitments from China and its willingness to join forces with the US are significant.

“The first agreement last November was historic,” Morgan says, “but now, to have something that's so detailed and for them to be coming together on core elements of the agreement itself, just shows that there is quite a lot of collaboration, and that they're both very committed to actually transforming their economies.”

Morgan says the new level of collaboration makes it harder for other countries to “hide behind” the US and China. “The two largest polluters are moving,” she says. “Each of them of course need to do more; but it's pretty unprecedented, this agreement.”

Many commentators and politicians have noted the irony behind China’s announcement: A communist country, China, centers its climate action on a market-based solution like cap-and-trade, while the democratic US is unable to take any legislative action, leaving President Barack Obama to take executive actions to address the issue.

“The fact that China is able to do this and put a price on carbon just shows how important it is,” Morgan says. “The US could do this much more quickly and much more easily with the [capitalist] system that we have here. Hopefully, it will raise some eyebrows [and] get some things moving in the US.”

Morgan sees a “positive competition” emerging between the two countries, one that can only bring more ambition for change and greater benefits to the crucial meeting in Paris.

About 75 countries have now made commitments to reduce greenhouse emissions ahead of the Paris conference, which covers nearly all the major emitters in the world. But so far these commitments are “more of a floor than a ceiling of the level of ambition of each country,” Morgan says.

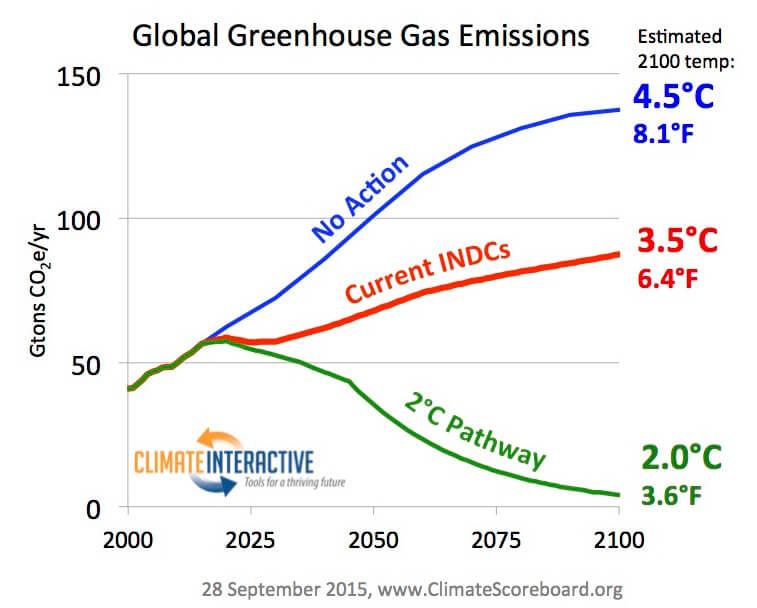

The group Climate Interactive, based at MIT, recently released an analysis of the pledges already made and found that they would reduce overall global warming to slightly more than 3.5°C by the end of the century. Most of the world’s scientists agree that anything over 3.5°C will have catastrophic consequences for the planet.

Morgan believes this analysis has incredible importance, because it emphasizes both the urgency of an agreement and the need for an acceleration of future reductions.

“I think one needs to look at more than just the math of these national plans to understand what's been set into motion,” Morgan says. “One needs to look at the scale up of renewables and the avoided lock-in of high carbon infrastructure that transports coal and oil. If you bring that into the mix, and if the agreement is solid, we still have a shot at staying below 2° C.”

Morgan believes a deal with binding limits will likely emerge from the Paris talks, but the unknown is whether it will be a one-off deal or something more transformational — a turning point, a new regime in which countries continue to work together to reduce emissions and to adapt to their impacts.

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?