Emerging from the spectre of Ebola

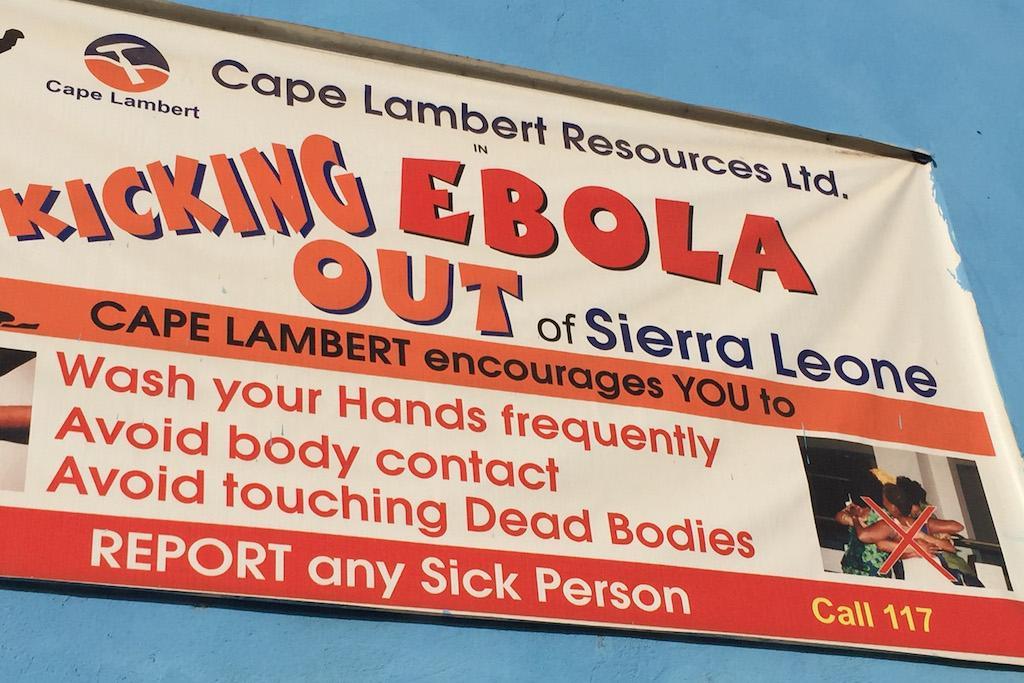

One of many banners around Freetown, Sierra Leone, warning people not to touch one another because of Ebola.

Ebola no longer rages in Sierra Leone. Instead, it appears here and there like a flicker of a snake in the bush. Officials caution civilians not to lapse into complacency, however great the temptation to return to everyday life.

Anti-Ebola banners remain around the capital city of Freetown. They warn people not to touch one another, to be weary of visitors and to call the authorities if a neighbor is suspected to be sick. Just last week, someone new was diagnosed with the deadly disease.

Yet the buoyancy of the land itself seems to rebel against these dreary rules. Along roads that bisect the country, blades of emerald grass sprout from rice paddies that stretch to the horizon. Heavy fruits — mangoes, avocados and plantains — tug on tree branches. In the pauses between the daily downpours of the rainy season, butterflies and small birds flit about chaotically.

I came back to Sierra Leone — a small, round nation nestled between Guinea and Liberia — to write about how the country’s hospitals might be strengthened in the wake of Ebola. I witnessed the outbreak's peak in December and flare throughout February. Nurses, lab technicians and assistants doubled over in exhaustion.

The feeble public health system had simply crumbled under the weight of Ebola. Many health workers lost friends and family members. The bravest had joined the battle against the contagion and they were beaten down. The best means of coping — the tactile comfort of others — was dangerous and therefore banned.

So an invitation from a stranger — an act prohibited under Ebola rules — was the first clue that things were different upon my return a little over a week ago.

To arrive in Freetown, you take a rickety minibus from the airport down a dirt road to a dock. From there, a motorboat carts passengers across the bay in small groups. My flight arrived at 4 a.m. The ocean was black ink beneath a blanket of stars.

Waiting on the dock, I struck up a conversation with a Mauritanian man with a red beard. He worked in the mining industry. Once we arrived on the shores of Freetown, he offered me a ride to my hotel. Anywhere else, I’d have thought him a creep. But after several visits to Sierra Leone, I anticipate kindness from strangers. Still, I decline. A friend awaits me at the other side. When I spot him, we pause and then break the decrees and hug.

Last month, there were a total of 234 new Ebola cases in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea. That’s seven times less than what it was when I visited in February—a month with 1,657 cases. As a result, everyone’s adherence to the Ebola rules has faded.

Freetown echoes with a cacophony of voices and songs. Sunday night, the beach was vibrant with nightclubs that had been shuttered until recently, while Ebola tore the city apart. Though the antisocial rules stand, you’d never know it.

“Such complacency!” bemoan government officials and aid workers who have orchestrated the Ebola response into its second year. Nonetheless, in private, they too shake hands, go to parties and hug their colleagues.

These days, each new case of Ebola is reported with a string of details. A couple of weeks ago, a man visited his home village in Tonkolili, at the end of the Ramadan holiday. He came down with a fever, and was diagnosed with Ebola on Wednesday. Two dozen people who had contacted him are now under quarantine.

A photo posted by Amy Maxmen (@amaxmen) on

This news seems dramatic from afar, but compared with the situation previously — in which people spoke of entire regions as “hot zones,” rather than individual cases — it’s a vast improvement.

Fear no longer permeates communities. And perhaps that’s not entirely bad. Before, I’d privately worried the disease might destroy the kindness that binds people together. Ebola turns you cruel.

One afternoon last December, I drove around Freetown with a commander in Sierra Leone’s army who was monitoring villages for potential Ebola cases. We pulled over at the side of a road, where an elderly woman had collapsed at the foot of a tree. Blood stained the fabric of her skirt. Her knee was bent at an impossible angle. She’d been hit by a vehicle the day before, she said, and could not stand.

She pleaded for help, but ambulances were reserved for Ebola cases only. Taxi drivers would not pick her up either for fear of the virus. For the same reason, the commander and I would not bandage her wounds, or take her to a hospital. We drove away, leaving the woman helpless in the hot sun.

Last week I visited a nurse I’ll call Faith Sesay, who had been pregnant with her first child while she toiled in an Ebola ward. In February, Faith and I spent hours together for an investigation I was working on into the lack of payment to nurses and other Ebola health workers. (Faith requested that I not use her real name in order to protect her job.)

She was angry about the absence of pay she had expected for her work at the hospital. She was also scared for her future as a young, single mother. The father of her unborn child had distanced himself from her because people feared Ebola health workers. Faith’s neighbors eyed her wearily.

Anxious memories of her have paced through my mind since then, and on this visit, I braced myself to hear how she had fared while I’d been gone.

A photo posted by Amy Maxmen (@amaxmen) on

Along the undulating dirt roads that lead to Faith’s house, women hung fabric on laundry lines in patches of sun. Stripes of light fell between stands of tall palms, fertile with palm nuts — a staple of the local economy. The silence of the day was pierced by a shout, and then I saw Faith leaning out of a window, her arms spread open. She ran outside, down the dirt hill towards the road, and we embraced each other for the first time.

A young man joined us in the yard, carrying a baby boy. Faith displayed a ring on her finger. They had been married the week before. She updated me on the hospital and her payment situation. It had not improved, but her husband interrupted her to suggest she put the stress over payment behind her. She nodded, and beamed at the baby, now in her lap. She named the child Prosperity — a beacon of hope after the darkest year.

Amy Maxmen is part of the global health reporting team working on "The Next Outbreak," a collaboration of The GroundTruth Project and NOVA Next.