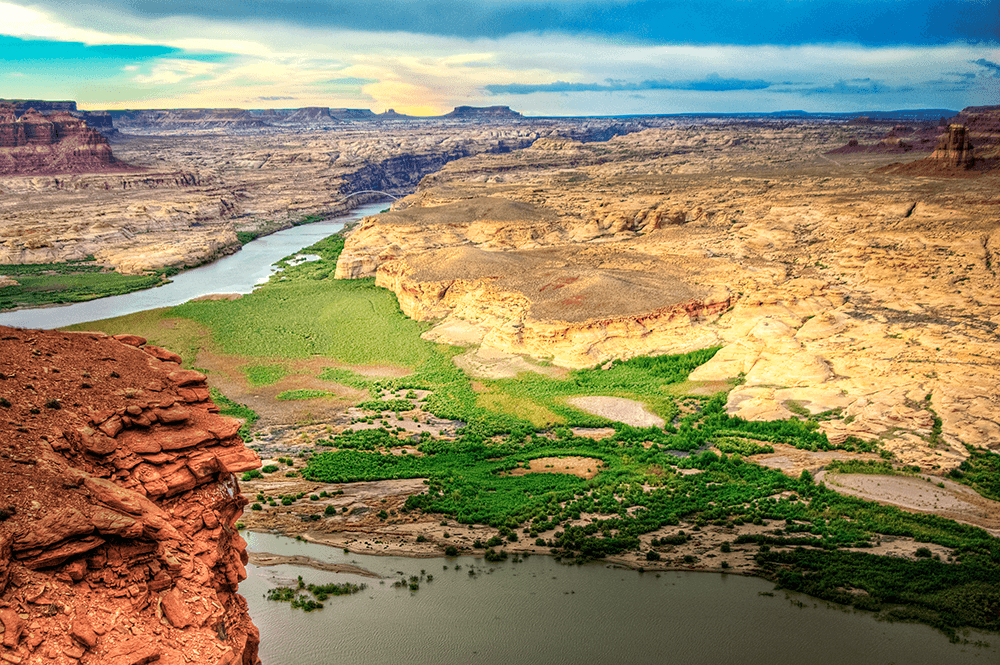

The Colorado River is crucial to the West’s water supply — and harnessing it was a feat

The Colorado River. Water-bans and wells running dry in the West isn’t only about the lack of rain.

Water supply in the West isn’t only about rain, or the lack thereof. A good deal of water scarcity issues have to do with decades-old policy on water issues and entrenched infrastructure.

It’s a convoluted situation, and reporter Abrahm Lustgarten of ProPublica is part of a team that is working to make sense and put broader perspective on the Western water crisis and the central role of the Colorado River. Their findings are being reported in a series called, “Killing the Colorado.”

Neither Phoenix nor Tucson would have been able to develop to their current sizes without the water collected at the Navajo Generating Station, a 2,250-megawatt coal-fired powerplant built near Page, Arizona, in the late 1960s.

The plant consists of three 775-foot tall caramel-colored smokestacks that burn coal dust. Its primary function was to provide power to move water through the Central Arizona Project, a canal that the state of Arizona and the federal government built to divert Colorado River water into the middle of the state.

The water has to travel up and over a mountain range — a climb of 3,000 feet— and across 330 miles. It takes an enormous amount of power.

Part of the plan at the time was to harness the coal reserves in the region and build a series of power plants, the keystone of which was the Navajo Generating Station.

Power to move the water and supply the growing cities would be produced as the station burned coal. About 22,000 tons of coal annually is brought by an electric railway from the Kayenta Mine about 85 miles away. The mine is on the Navajo reservation and is excavated by Peabody Energy, one of the largest mining companies in the world.

“All of these cities have used enormous engineering efforts to move water over hundreds of miles with enormous amounts of energy in order to support a population boom,” Lustgarten said. “While in some ways they've been efficient about the way they’ve used water, just the relative growth in the number of people there has meant that they always need more and more of it.”

Post-war development asserted a can-do attitude behind the building of these power plants. TIME magazine described the plan as something that would dwarf the Tennessee Valley Authority project, Lustgarten says.

“It was really going to be the biggest power production project that the nation had ever seen,” Lustgarten says.

And throughout the plan, Lustgarten says, was the underlying feeling of “engineering our way out of what was always an environmental crisis."

“There was never enough water in the West and that was always understood. So each of these projects were always seen as a way to try to trump nature basically by building bigger and more powerful things.”