A deal on Africa’s biggest dam eases tensions on the Nile

Ethiopia's Grand Renaissance dam on the Blue Nile, shown under construction in March of 2014. Egypt claims most of the water in the 4,000 mile-long river that it shares with 10 other countries, and fears the $4.7 billion Renaissance dam will reduce the water supply for its 84 million people, who mostly live in the lower stretches of the river. But this month it struck a deal with Ethiopia and Sudan to let the project proceed.

After years of wrangling, Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan have agreed to a controversial hydroelectric dam, Africa’s biggest, being built on a major branch of the Nile River.

Under the deal, Ethiopia will give Egypt a share of the electricity from the Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam project. Ethiopia also has promised the project will “not damage the interests of the other states” involved.

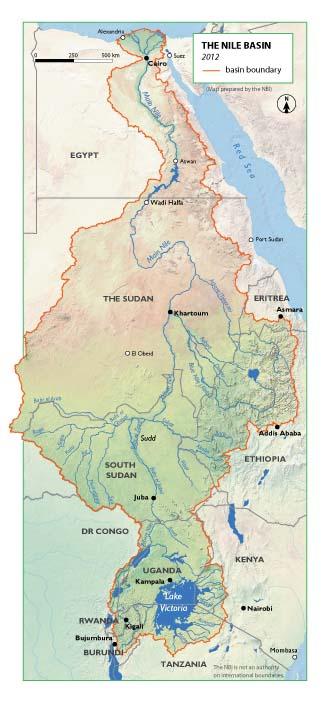

The Nile is the world’s longest river, running more than 4,000 miles from the lakes region of East Africa to the Mediterranean Sea. It’s also one of the world’s most contentious, with nearly a dozen countries vying for control of its waters.

The tension has been especially high recently between Egypt, which has historic claims to most of the Nile’s water, and Ethiopia, which has big plans to develop water resources on the Blue Nile and other tributaries. Not long ago, Egypt all but threatened war if Ethiopia built the Renaissance dam.

The history of claims and counterclaims over the Nile stem from the river system’s peculiar physical and political geography. Unlike other great rivers such as the Amazon, the Yangtze, and the Mississippi/Missouri system, which flow mostly or even completely through just one country, the Nile watershed covers parts of 11 countries.

That in itself is likely to create conflict.

But for such a huge river system the Nile actually carries very little water, because much of its watershed is very dry, especially the downstream main stem in Sudan and Egypt. That amplifies the likelihood of conflict, as does the fact that the countries in the region are all relatively poor, with growing populations, and so are looking at a growing demand for water.

The new agreement doesn’t settle all concerns about the Renaissance Dam, or others on the drawing boards. Egypt says it’s still worried about its impact and there’ll be further talks about the details. And the deal doesn’t seem to do anything to address the environmental and social impacts of this dam or others on the river system.

Still, by all accounts a significant step forward on cooperation in the region.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!