Business-minded immigrants often turn to gardening work because the start-up costs are relatively modest — namely the price of the truck and the gardening equipment.

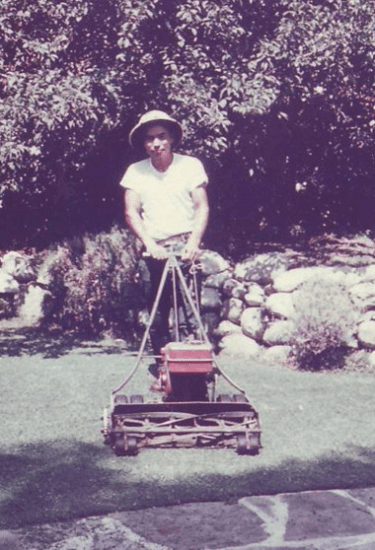

The people who run California's ever-buzzing leaf blowers, weed whackers and lawnmowers are almost always Latino immigrant men. They call themselves jardineros, Spanish for gardeners, and it’s their labor that gives curb appeal to so many homes, keeping lawns neatly trimmed, hedges pruned and weeds at bay.

One professional jardinero is Efraín Valladares, a Mexican who's been working in the US doing garderning work for 18 years. I meet him while he takes a lunch break in his pick-up truck on a busy street in Los Angeles. "We're important because it wasn’t for us — the jardineros — what other group would be doing this?" he asks. "Right now we’re … purely Latinos working in gardening.”

"It’s impossible to imagine California gardens without immigrant labor," says Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo, a sociologist at the University of Southern California and author of "Paradise Transplanted: Migration and the Making of California Gardens."

But those immigrants weren't always Latinos. Hondagneu-Sotelo says the labor force tending California’s gardens was actually once dominated by Japanese. "Japanese men really developed the occupation of suburban maintenance gardening," she says. "They were the forerunners of the work now largely performed by Latino immigrant men."

But the gardening business experienced a big shift in the '60s and '70s as Mexican migrants took up the occupation — often starting as understudies to the Japanese. "Mexican men started as the waged employees of Japanese gardeners," Hondagneu-Sotelo says. "They eventually then assumed the title of what we call the 'route owners,' or the men who owned the tools, the trucks and who had direct contact with the households where they were working.

These days, Latinos dominate all of the rungs of the gardening hierarchy. A jardinero who owns the gardening truck and equipment and talks to the clients might have one or more ayudantes, or helpers, who work under him. Filiberto Sánchez is one of those ayudantes, working for another Latino gardener. But he’s looking to move up.

"The truth is I’m trying to get my own route," he says. "Right now I work for my boss during the week, but on Saturday I work for myself to get my own route and clients. I don’t want to spend my whole life working as an ayudante."

Yet as they try to find success here, you also hear how paid gardeners get criticized in California. It's often because of the sound of leaf blowers. They're standard gardening equipment but loathed by many residents — like Ann Jones, who says the machines intrude on neighborhood peace and quiet.

"I’m sure the gardeners would rather use them but, you know, they could go back to using rakes and just raise their prices. That’d be fine with me," she says.

But Hondagneu-Sotello says jardineros know that raising their prices means potentially losing clients. The blowers help them work faster and cheaper — and keep them in business.

"Jardineros are now competing against one another and they know that to make it work for them, they need to do a lot of different yards in a short period of time," she says. "Volume counts, as many jobs as possible counts."

And, like the Japanese American gardeners who came before them, many jardineros dream about another kind of life for their children.

One of them, Hugo Perera, works raking leaves in front of a large home. He’s with his 7-year-old son, Antonio, who sometimes helps him on his gardening route. Perera wants his son to go to university and have a different kind of life.

It's a reminder that the noise of a lawn mower can also be the sound of someone trying to get himself — and his family — ahead.